1. Overall context

Much water has already gone under the bridge on this topic. Yet the flow shows no signs of coming to a halt soon. In the early days of the so-called “Internet revolution,” only a few were connecting the two. At the 1992 UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, which I had the fortune of attending, technology was essentially a non-entity at the official proceedings – even though we were using the emerging Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) to connect people at the Summit and with the world – then limited to a selected group of countries that had access to the global network. The Summit’s outcome document, Agenda 21, was endorsed by UN member states but only included two references to “information technology.” The first called for increased access to ICT. The second suggested research and development of relevant hardware, software and other elements of information technology to tackle the specific needs of developing countries. While mentioning data, information, knowledge and expertise, the Agenda’s Chapter 4o on Information for Decision Makers failed to find any links with the emerging digital technologies. On the other hand, sustainable development (SD) appeared on almost every document page and was unanimously the much-sought long-term development outcome.

In hindsight, the UN 2000 Millennium Declaration and the 2001 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were a bit of a setback for SD. The powers that are managed to steer the development agenda toward poverty reduction, health, education, gender and human rights while making SD one of the eight core goals but rebranded as environmental sustainability. SD was thus asked to compete with the other goals and reduced to basic ecological management. On the other hand, ICTs gained significant territory as they captured one of the targets of MDG Eight, focused on promoting the then-emerging concept of public-private partnerships. Its scope, however, matched that of Agenda 21 with its monovision on access – at a time when the digital divide ruled. Moreover, links between the latter and all other goals were also missing in action. That prompted a reaction from ICT practitioners who analyzed all MDGs targets one by one and plugged technology where appropriate. Nevertheless, such a shopping list exercise yielded little results as the relevance of the new technologies in promoting core development goals was still in doubt – with little on the ground evidence to claim otherwise. So the “PCs vs. Penicillin” debate raged on.

While supporting many of the now-defunct MDGs, the 2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) brought back SD. It was once again the overall outcome, while seven new goals addressed specific SD issues ranging from energy and clean water to climate change and sustainable livelihoods. Although the SDG document avoided the acronym, ICTs also gained ground. The access target was preserved but limited to least developed countries. And for the first time, digital technologies were seen as part of the solution to achieving education, gender equality, and science, technology and innovation targets. Undoubtedly, the “data revolution” hype at that time helped overshadow the relevance of ICTs in most SDGs.

Overall, it seems clear that the various global development agendas have had a rocky romance with ICT. And while a complete divorce is not in the cards, the links between the two remain elusive in theory and practice.

2. Sustainable development revisited, again

A recent academic article that I will review in a later post takes stock of ICTs’ alleged impact on the economy and the environment. No doubt such a seemingly perfect trifecta is prone to complex internal power distribution analyses. The document studies over 100 research articles that have attempted to decipher the interdependencies that drive the trifecta’s internal dynamics. Surprisingly, very few directly reference SD, a concept initially developed by the Brundtland Commission in 1987. It has certainly changed over time, albeit slightly. For example, the UN SDG official document adds poverty and inequality reduction but still hinges on three core components.

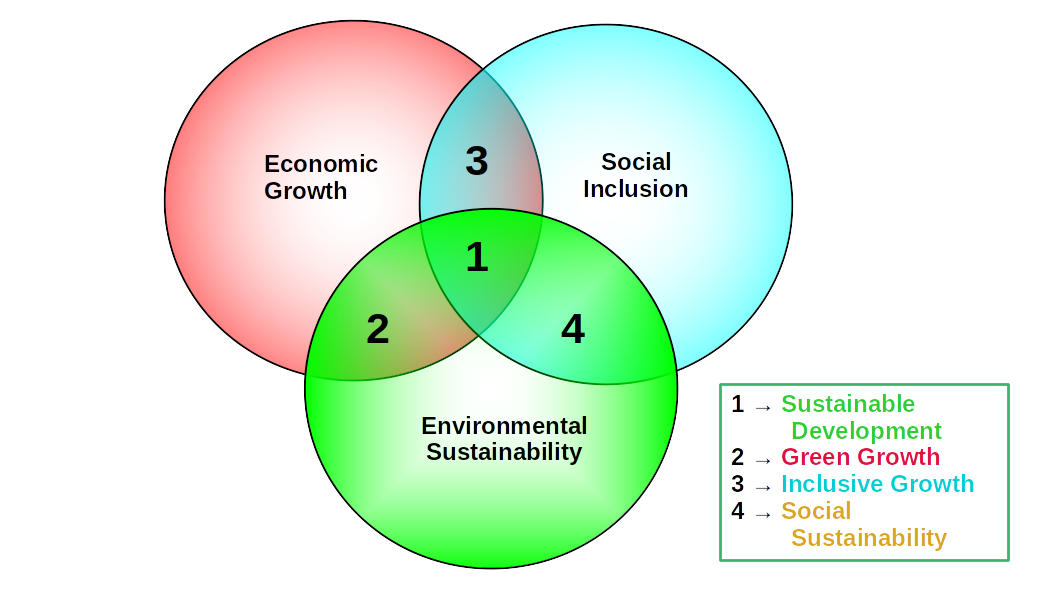

In a nutshell, SD is defined by the intersection of three developmental outcomes: 1. Economic growth. 2. Social Inclusion (social equity in 1987) and 3. Environmental sustainability. The figure below depicts such an intersection.

As is typically the case with Venn diagrams, we get more than what we bargained for. In addition to SD, three other categories pop up, depending on the various intersections between category pairs. One significant result is that economic growth, the core engine of Global Capitalism, has four distinct personalities ranging from pure growth to SD. Inclusive Growth and Green Growth can each occur independently without necessarily promoting SD. Second, Social Sustainability (a concept endorsed by the World Bank) seems to sit at the other end of the spectrum as it can be seemingly achieved, in theory, without economic growth. Under what circumstances is such a thing possible, if at all? That could be the topic of yet another set of new academic papers.

As is typically the case with Venn diagrams, we get more than what we bargained for. In addition to SD, three other categories pop up, depending on the various intersections between category pairs. One significant result is that economic growth, the core engine of Global Capitalism, has four distinct personalities ranging from pure growth to SD. Inclusive Growth and Green Growth can each occur independently without necessarily promoting SD. Second, Social Sustainability (a concept endorsed by the World Bank) seems to sit at the other end of the spectrum as it can be seemingly achieved, in theory, without economic growth. Under what circumstances is such a thing possible, if at all? That could be the topic of yet another set of new academic papers.

Furthermore, I will argue that the economic growth side of the diagram has a historical background. The initial stages of Capitalist development in England followed the pure economic growth dynamics. With the imponderable help of Colonialism, the Second Industrial Revolution propelled more inclusive growth in capitalist nations, as reflected in the emergence of the so-called middle classes. A similar evolution occurred in countries that became capitalist in the 20th Century, such as China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. As a concept. Green Growth saw the light of day in the 1970s. Still, it became a reality a decade later when governments in advanced capitalist nations started tackling deforestation and air and water pollution while not always considering the social inclusion dimension. In fact, several developing countries adopted similar policies that increased social exclusion by targeting the poorest sectors of the population as primary polluters. Furthermore, Social Sustainability predates Capitalism as indigenous communities have usually adopted it and continue to do despite intense pressure to do otherwise in many countries.

Finally, SD is also the result of a ménage à trois, but the characters involved in that passionate affair do not match those of our first trifecta. Not only is social inclusion missing from the latter, but the multipolarity of economic growth is totally disregarded. Instead, the implicit assumption seems that economic growth by default encompasses green and inclusive growth and propels inclusion automagically. I am convinced digital technology academic researchers working on the topic should be fully aware of these subtle but critical differences in the categories they seem to use without giving them more detailed thought.

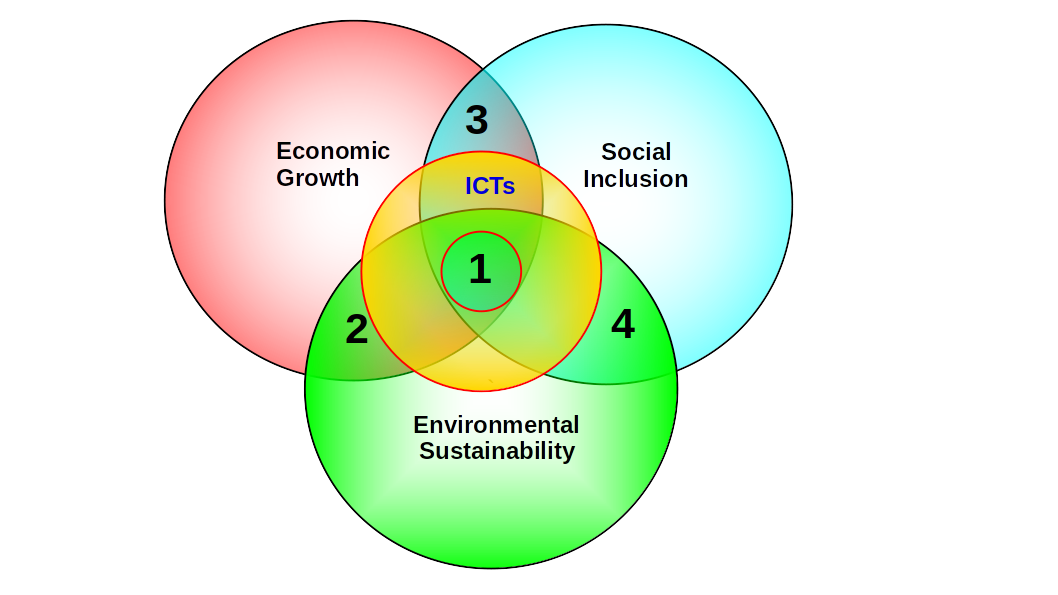

In any event, now we need to find a way to combine the two trifectas while avoiding having one character too many in the mix. Here, the more, the less merry. At first sight, ICTs seem to be the spoiler, an outlier of sorts. Indeed, as we saw in the first subsection, their relationship with SD is still under much debate. But perhaps more importantly, we should note that ICT, unlike the other players, is not a development outcome. As we will see, it is more of a catalyst with a few wrinkles here and there.

3. Slippery development curves

Before fully introducing ICTs into the overall SD picture, it is vital to have some basic understanding of the interaction between its three core components. Needless to say, there is a vast research literature that we should carefully consult. But for my purposes here, I will only focus on the impact of economic growth on social inclusion and environmental sustainability to illustrate the issues at stake.

As mentioned above, the SD definition used in the SDG document includes poverty reduction and inequality. Therefore, we can use the latter as a good proxy for social inclusion and assume that economic growth in an ideal Capitalist world should reduce inequality in the medium and long term. In the mid-1950s, economist Simon Kuznets developed his now world-famous Kuznets curve (KC), which eventually became one of the “laws” of neoclassical economic growth theories. The argument here is that in the early stages of development, economic growth increases inequality, but as overall per capita income increases over time, it reverses course and starts to fall. An inverted U-shaped relationship thus exists between the two. In other words, we move from pure economic growth to inclusive growth over time. Kuznets’s explanation for such a peculiar trend was based on urbanization and industrialization.

Almost sixty years later, the publication of Piketty’s best-selling book put KC on notice. Indeed, Piketty showed that income and wealth inequality had risen since the late 1970s in core Capitalist countries while showing no signs of retreat. We are still there today and waiting for the inverted U-turn to happen. The light at the end of this tunnel has now gone off – hopefully not for good. Of course, many have come to the defense of poor Kuznets, who allegedly argued that his hypothesis was based on scarce data and was less anal about his purported “law.” Regardless, we are now hearing noises about the new Kuznets wave that supposedly behaves like the economic business cycle but operates in the long term only. However, a cohesive theory that explains such a long-run Kuznets wave seems to be missing. The other issue with the original KC is its relevance for emerging and developing nations. Brazil, Russia (since the 1990s) and South Africa, for example, have certainly never seen the curve’s iron “law” work within their national boundaries. A fundamentalist Popperian (which I am not!) would summarily conclude that KC has been falsified. Not so for mainstream economics.

Regardless, in 1992, the same year of the Earth Summit, the World Bank came up with an extension of the KC, now applicable to environmental sustainability. Christen as the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), the new inverted U curve correlates economic growth with the environment. And as with the original, the EKC allegedly shows that economic growth has a negative impact in the early stages of development, which is then reverted in the long run. The initial research on EKC was focused on air and water pollution and used econometric models to show its statistical significance. We also know that many governments in advanced Capitalist nations started tackling air and water pollution in the late 1970s. In this light, one could argue that government policies and regulations were the primary triggers for the EKC. In the case of CO2 emissions and others, the evidence is less solid. While academic research continues to study the relevance of EKC, the jury is still out.

As with the KC, evidence of the EKC in emerging and developing countries is comparatively much weaker for Co2 emissions. For example, data for BRICS nations show that GDP per capita and CO2 emissions grow hand in hand, showing no signs of reversal so far. The same goes for a few other developing countries. So here we have an EKC bifurcation where it seems to operate within advanced Capitalist countries but does not show up for the rest.

In my book, the most important critique of the EKC stems from the concept of carbon budgets, a stern reminder that the environment is a finite resource. The EKC measures the relative correlation between GDP per capita and environmental degradation. When the curve starts to descend, if ever, we cannot assume that environmental degradation has stopped altogether. All we can say for sure is that one (GDP) is moving slower than the other, but both could be, in fact, increasing. So even in the cases where the data shows a functional EKC, we cannot say that Co2 emissions have stopped. CO2 data for the last 50 years shows such an ideal point has never been reached. Suppose we insist on any curve between economic growth and environmental sustainability. In that case, the best one is the good old logistic curve where one can see continuous growth that slows down at the top – and will stop for good once the environment collapses. That also partly explains the dubious Net-Zero principles adopted by CoP26, spearheaded by industrialized countries.

We are thus moving within deeply contested territories filled with extensive swamps and hidden quicksand spots. Try not to get stuck.

4. ICTs for what?

I first saw a catalytic reaction in high school while participating in a mandatory chemistry course lab exercise. I do not recall the exact experiment, but I do remember it had a positive impression on me. It was totally cool to see how adding a particular substance to others could trigger and/or accelerate a chemical reaction while leaving the added substance unscathed. Chemical magic realism, I thought. Nowadays, most cars have catalytic converters that use the same principle to reduce (but not eliminate) emissions. Of course, catalysts exist outside the chemistry realm but are defined similarly. In a nutshell, catalysts are factors that promote change without being changed themselves while acting as such.

I will submit that, from a development perspective, ICTs should be seen as catalysts first and foremost. In this light, ICTs can amplify development processes, accelerate the achievement of development goals and targets, and transform how we tackle development gaps. Linking this idea to more regularly used concepts such as efficiency, cost reduction, scalability, replicability, participation, transparency and accountability, among others, is thus essential.

As catalysts, ICTs cannot be and should not be seen as a development outcome. At best, they can be development outputs, a factor that, combined with others, contributes to achieving specific development outcomes. On their own, ICTs cannot achieve much from a purely developmental perspective.

Of course, ICTs must be produced, distributed, exchanged and consumed. But here, ICTs are just another economic sector operating similarly to most others. They can thus contribute to economic growth in all its various incarnations and even become one of its main drivers. However, most developing countries have incipient (if at all) ICT sectors, so they have yet to see any significant benefits from such a development. Moreover, let us not forget that the ICT sector is complex and involves many other sectors and actors ranging from mineral extraction to sophisticated applications to guesstimate users’ preferences, as highlighted in Crawford’s latest book.

Bearing in mind these three core ICT characteristics (catalyst, output, and sector), we can now introduce them into the SD dynamic, as shown in the figure below.

ICTs can thus interact with or catalyze any of the seven subsets or development outcomes that comprise the action and interactions of SD’s three core pillars. Researchers and practitioners should be fully aware of the various options and potential outcomes available. For example, ICTs can surely help promote Green Growth, but that does not immediately translate into overall SD if the social inclusion outcome is missing from the overall approach. On the other hand, ICTs can also expedite traditional economic growth and ignore social inclusion and environmental impact if their direct impact (ICT production) is more significant than their indirect ones (ICT as a catalyst). In this regard, recent estimates suggest that while ICTs are responsible for 2 percent of emissions (direct impact), they could also bring a 16-17 percent reduction when used indirectly in other sectors of the economy.

In any case, nothing within ICTs’ nature suggests that their deployment is always for “good” by default. Instead, a more suitable answer is to be found on how we plan to use them in a specific development context.

Cheers, Raúl

Comments

One response to “Digital Technologies and Sustainable Development”