Country data typically provides a comprehensive macro overview of the current status of a particular theme, such as data centers in our case. The same goes for CO2 emissions, for example. On the other hand, countries are geographical abstractions that posit the topic within well-defined boundaries, where a national state exercises its sovereignty to the best of its capacity. Countries, per se, do not emit carbon. Instead, it is the direct and indirect interactions of its inhabitants with the environment that trigger the poison through the production, circulation, and consumption of goods and services of all kinds. CO2 emissions are thus a function of population and economic activity. A country with a large population can, in fact, emit little carbon if its extractive economic activity is limited. And vice versa. In that light, emissions per person are a much better indicator of a country’s actual contribution to climate change.

A similar situation unfolds with data centers. These digital factories are highly dependent on land, water, and energy resources, thereby imposing a significant burden on local ecological footprints. Investors will assess their accessibility first and foremost, before taking the leap. Data centers are therefore bound by the vicissitudes of localization. They thus need to delve deeper into national contexts. The macro level is just the first threshold they need to cross. Investors desperately seek cities and towns where such resources can be secured for the foreseeable future. Economic incentives, such as tax breaks, subsidies, and/or special deals with local water and energy suppliers, are also part of the investment decision process. More often than not, local governments play a critical role here. In any case, the data center business literature refers to such places as “markets.” Let us then take a close look at these exciting places.

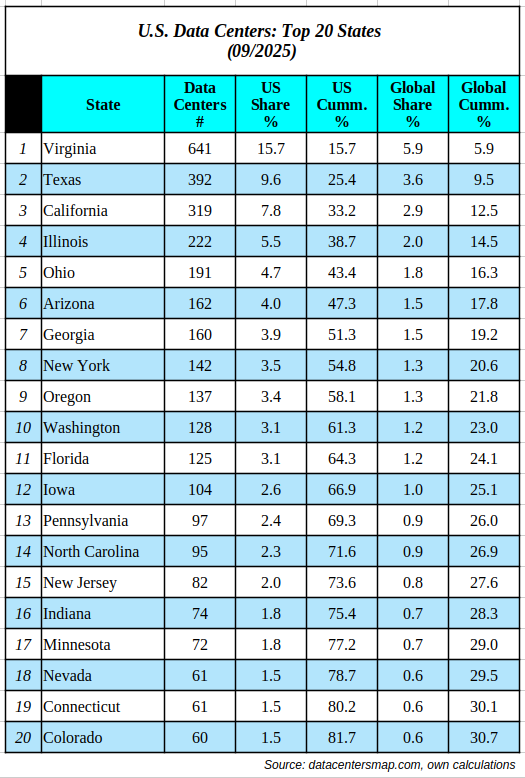

We already know that the U.S. is an outlier, as it hosts nearly 39 percent of all data centers worldwide. So, where exactly are these noisy and thirsty factories located? The table below depicts the distribution for the top 20 states in the country.

The rumor is indeed accurate. Virginia is the U.S. data center champion by a wide margin, with almost 16 percent of the total, leaving Texas and others in the dust. In fact, there are approximately 7 data centers for every 10,000 Virginians. The majority are located in the state’s northeast, not far from Washington, D.C. If Virginia were to become a country, it could claim the top spot globally, easily surpassing the UK (490), Germany (484), and China (379)—the countries that follow the U.S. with binoculars in the data center race.

The table also shows that the top ten states account for 61.3 percent of the data centers, totaling 2,494. And two states, Virginia and Texas, host 25 percent of them. We can therefore conclude that state data center centralization is also at work here. Nevertheless, it is not as extreme as the global distribution of digital factories we previously identified.

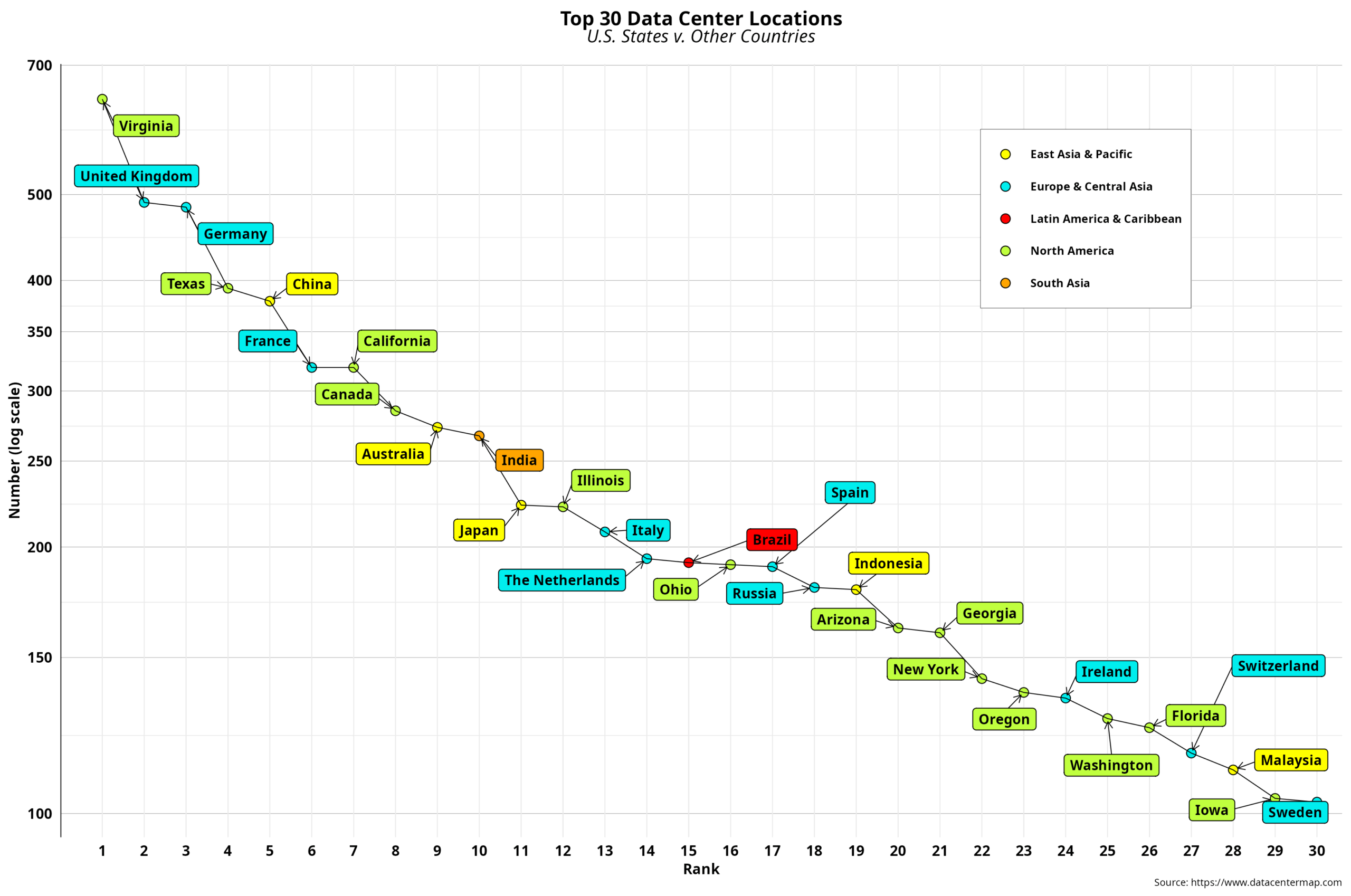

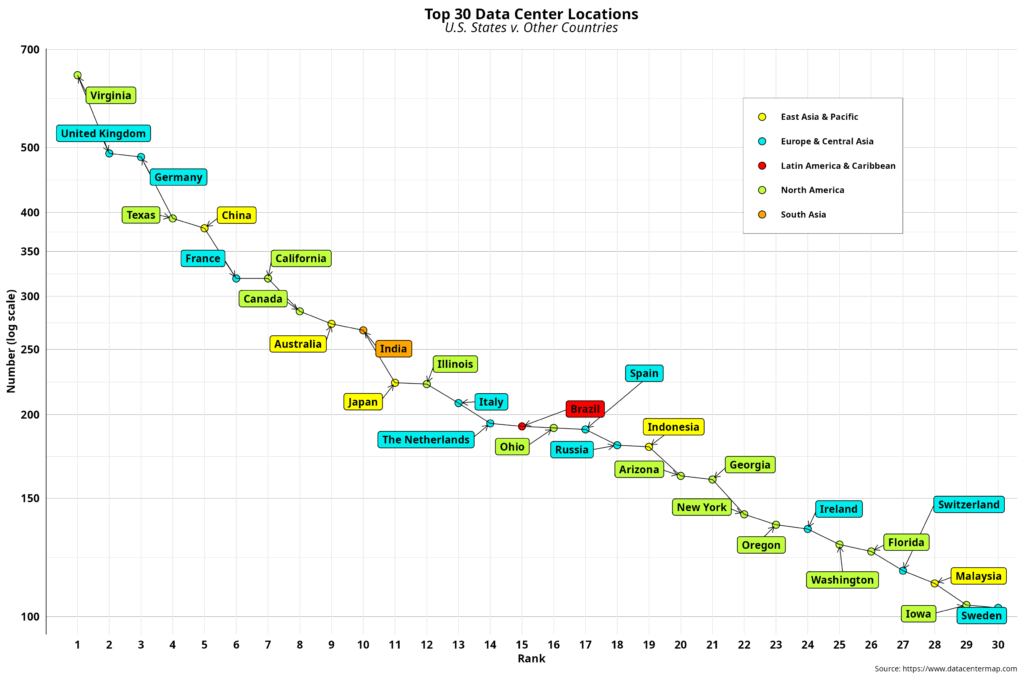

The table’s last two columns introduce the international dimension. The top 10 U.S. states account for 23 percent of all data centers globally. Moreover, while Virginia and Texas fall short of 10 percent globally, they host almost as many data centers as India and China combined, which together account for 35 percent of the world’s population. The graph below provides additional detail on the international dimension.

Note that countries from MENA and sub-Saharan Africa did not make the cut. And LAC has only one representative, Brazil. That said, 12 U.S. states are part of the top 30 data center locations. Texas is ahead of China, the alleged hegemony contender. And Illinois and Ohio beat Russia to the punch, each with a population size less than 10 percent of Russia’s. In fact, Virginia and Texas together have more data centers than the total for LAC, MENA, and sub-Saharan Africa combined. In sum, the global centralization of data centers is complemented by the national centralization in the leading country. Investors now have a more in-depth understanding of the data center market. They will look last at developing economies or at U.S. states such as Alaska and Vermont that host fewer than five digital factories.

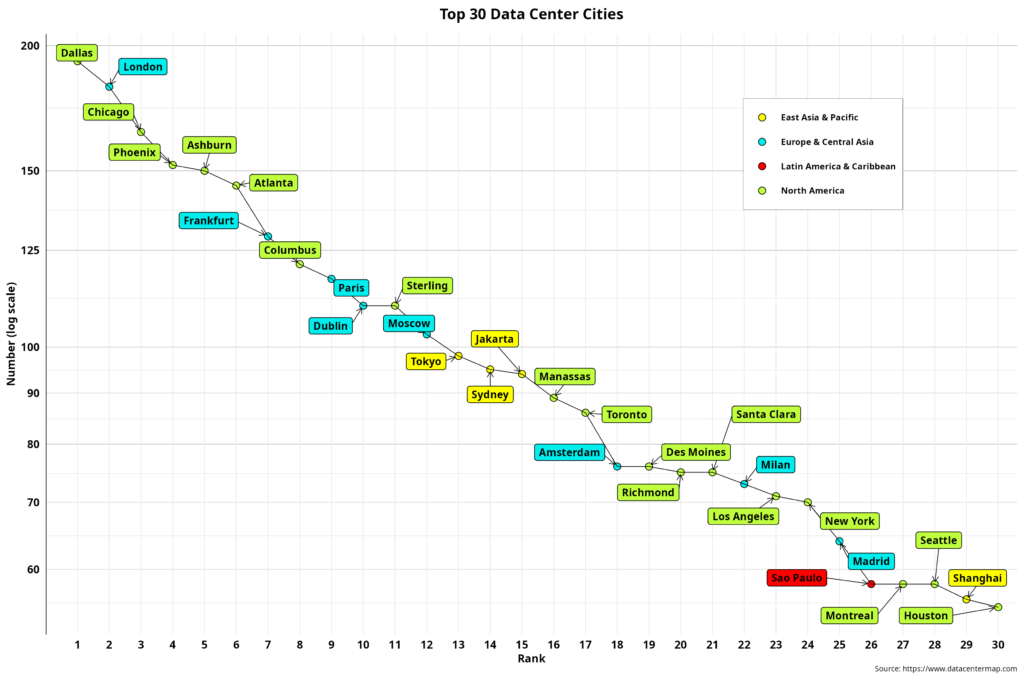

The chart below depicts the world’s top 30 data center cities. Here, we encounter a few surprises.

While Virginia is the leading state, Texas hosts the world’s data center champion city: Dallas. However, Virginia has the most cities in the top 30, with four (Ashburn, Sterling, Manassas, and Richmond), which account for 66 percent of the state’s total. Moreover, six U.S. cities are among the top ten, while only two from the Global South are represented: Jakarta and São Paulo. No city from India is part of such a prestigious tech club. Seventeen cities are from North America, with the U.S. alone accounting for 15 —50 percent of the total. Eight are European cities, with London leading the pack. And once again, MENA and sub-Saharan Africa are conspicuously absent.

One interesting pattern emerges from the data. In most cases, the leading cities account for a significant portion of all data centers within the U.S. state or country under consideration. For example, Dallas hosts almost 50 percent of all Texas data centers, while London accounts for nearly 40 percent of the UK’s data centers. While Phoenix and Atlanta host over 90 percent of all state data centers, Chicago, Des Moines, Columbus, New York, and Dallas share over 40 percent. In addition, Dublin, Moscow, Tokyo, Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Milan host 35 percent or more of all country data centers. It is thus evident that data center diffusion is inherently uneven. In other words, data centers attract more data centers. The question is whether the ongoing AI boom/balloon will change this pattern before it bursts.

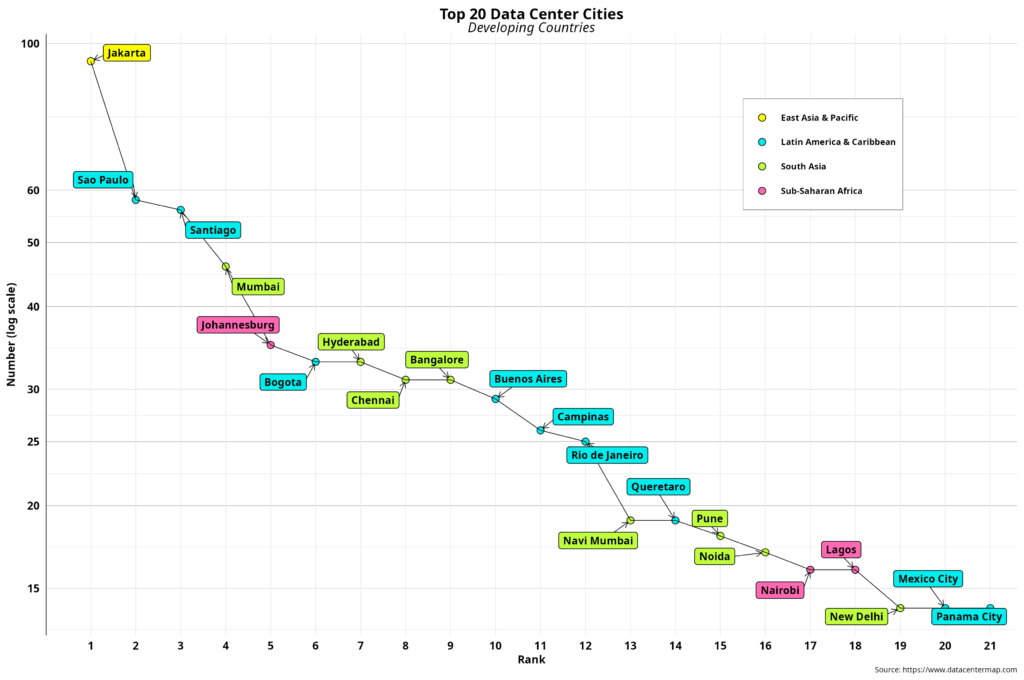

We can now examine cities in the developing world, as classified by UNCTAD, excluding those in China.

Jakarta is the “Dallas” of the developing world, with 94 data centers. São Paulo and Santiago follow from a distance, with 58 and 56, respectively. In addition, India has the most cities —eight — followed by Brazil with three and Mexico with two. Sub-Saharan Africa finally shows up with three cities, led by Johannesburg, which, in turn, is well ahead of Nairobi and Lagos. Note also that only the three top cities have more than 50 data centers, while those at the bottom record low numbers, certainly when compared to the top cities globally.

However, just like their top-ranked peers, these cities usually host the vast majority of country-based data centers. That is certainly the case for Panama City (93 percent), Santiago (86 percent), Lagos (84 percent), Nairobi (80 percent), Bogotá (79 percent), Buenos Aires (71 percent), Johannesburg (62 percent), and Jakarta (53 percent). Indian cities are a notable exception, as none has a share larger than 17 percent of the country’s total. In any case, centralization is even more pronounced here than in the developed world.

Raul