Needless to say, digital technologies are not strangers to the public sector. Indeed, Digital Government (DG) has been the subject of extensive academic research that has showcased frameworks, opportunities, and failures, including in the Global South. Initially born as e-government, the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in and by the public sector has evolved substantially over the years. E-governance, Transformational Government, Lean Government, Open Government, Smart Government, Intelligent Government, and Digital Government have been used to depict such interventions .

Since its birth, the United Nations has measured its evolution biennially . It is, therefore, surprising that most of the literature on AI in the public sector remains oblivious to such a body of knowledge and research. .

In that context, the critical dynamics between AI and ICTs, examined in a previous post, fall through the cracks, thereby opening the door to public sector standalone AI implementations that could do more harm than good—as occurred earlier with government ICT investments. And while AI can indeed be disruptive, that does not automatically imply that past ICT investments should be obliterated. On the contrary, the core research and policy question is how AI could impact current ICT deployments in the sector.

For our purposes, DG can be defined as public investments in digital technologies targeting the modernization of the public sector to augment its capabilities, improve responsiveness and scale up public service delivery . How such investment decisions are reached is a unique trait of public institutions—unlike the always-hungry-for-profit business sector. Whether beneficiaries and other stakeholders are part of such decision processes is thus critical if the ultimate goal is to increase public value. DG comprises three interconnected pillars: Policy/participation, public administration, and service delivery.

While some academic literature also highlights the same pillars , sequencing them is largely missing in action. The policy and participation pillar is essential to achieve optimal results from governance and public value perspectives. Whether such participation is via ICTs is less relevant than ensuring binding governance mechanisms are in place to enable and make stakeholder engagement possible and meaningful. In Global South countries with low ICT penetration, that is undoubtedly essential. In practice, service delivery is usually the starting point, thus ignoring the other two core pillars. Not surprisingly, failures are more than frequent .

DG’s three pillars can also be framed within the three core areas of public value: legitimacy, capacity and public service impact. Indeed, stakeholder participation is central to any process legitimizing public sector investments or policymaking. Creating and deploying capacity within public administration is central to increasing its capabilities to deliver services effectively and at scale. Finally, service delivery is central to improving the public value of public institutions’ programs and projects. Such a convergence just confirms that DG is not merely a technology-driven process. Instead, it has to be posited within a democratic governance context in which public technology investments improve the population’s quality of life. The same goes for public sector investments in AI.

One of the leading research questions should be how AI and its various incarnations impact these three layers. AI investment decisions must go through the same decision processes and governance instances to become a reality. Investing in sophisticated AI algorithms and platforms with more significant opacity and less explainability immediately introduces new governance issues that older ICTs did not raise. Thus, the analysis should study that and explore new or updated governance layers that could address related risks and potential failures.

While its potential impact on the public sector remains uncertain, AI technologies introduce critical governance issues —previously considered background noise —into the fray. During the “classic” DG age (1999–2006), public investment decisions to adopt digital technologies were not under direct scrutiny. The emergence of open data and social media started to turn the tide, and stakeholder participation and direct involvement in decision-making processes became relevant. AI has added more nuance here by directly questioning such processes while adding themes (responsible, ethical, non-discriminatory, unbiased, development-oriented, inclusive, etc.) that must be carefully considered when making public investment decisions.

The DG definition presented above centers on the unique traits of the public sector and its governance mechanisms embedded in context-based power configurations. Thus, it is not only about the type of technology being embraced, but, most importantly, why and how it is, and who is calling the shots. The same goes for AI. Indeed, AI and GenAI’s seemingly disruptive nature does not issue a license to bypass decision-making processes, ignore the dynamics of the public sector or skip much-needed sequencing.

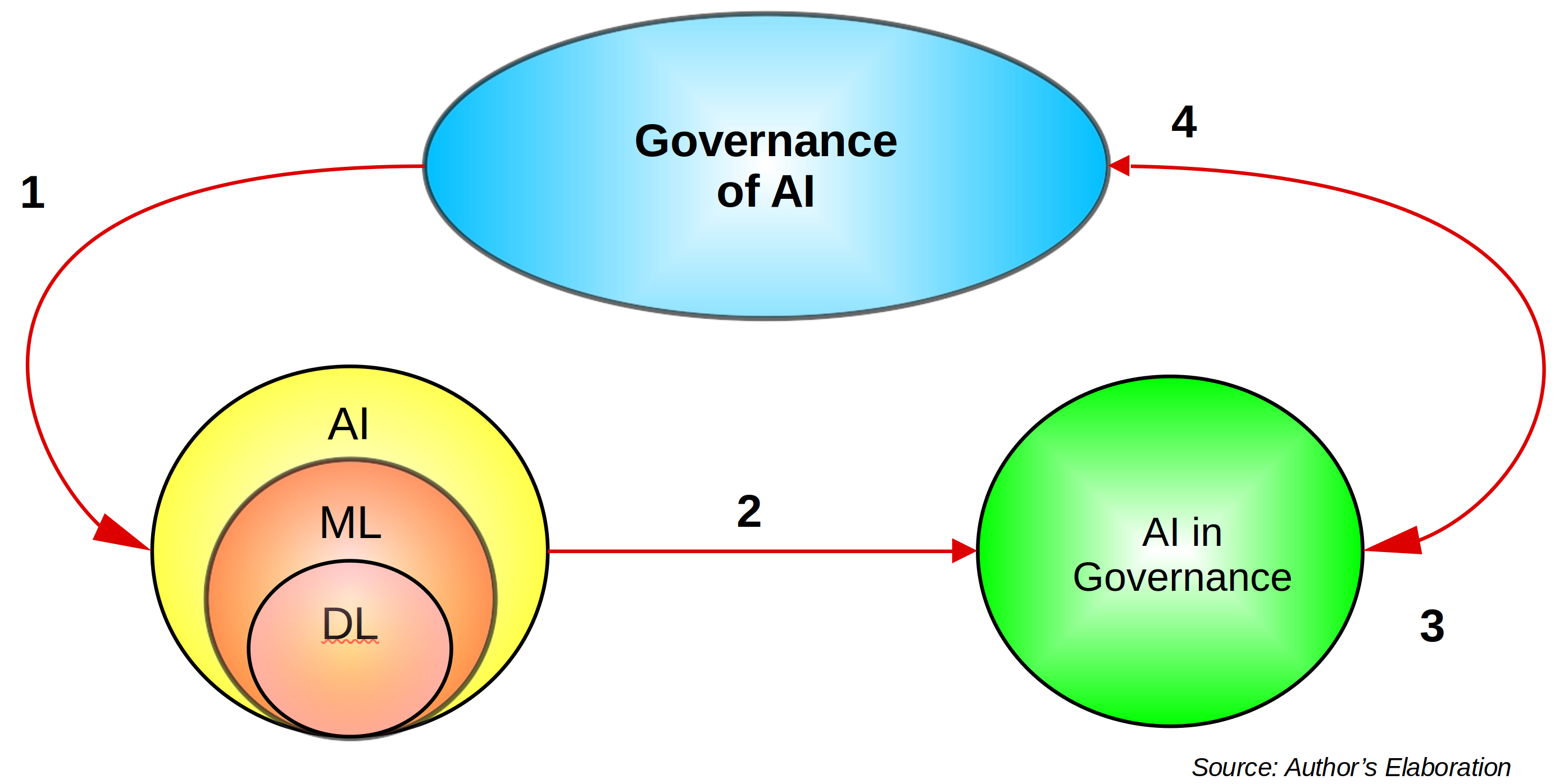

AI in the public sector comprises three interrelated dimensions. 1. AI deployments to enhance public administration and service delivery and augment public value. 2. AI in governance processes. And 3. The governance of AI. Comparatively speaking, the first element has attracted the attention of many researchers . Moreover, these case studies pick on the ten core functions of public administration previously mentioned, highlighting general public service, economic affairs, and public order and safety. At the application level, chatbots have received surprisingly high priority from governments in the Global North. However, most case studies do not detail the specific AI platforms deployed or examine relevant governance arrangements. Moreover, most of the research lacks an adequate AI typology that could have served to identify the selected AI platforms. Instead, models, algorithms and applications are meshed into a single category. I have already developed a typology to address the latter issue.

As with older ICTs, AI can automate public sector processes. Moreover, It can change them by eliminating redundant ones, simplifying others or augmenting the rest in scope and reach. That is a complex process in which people and older technologies are at stake, and decisions on moving forward play a critical role. Again, governance structures and instances play a central role here, while technology offers only a range of alternatives to build upon — but can never decide on its own.

GenAI, with its seemingly general-purpose capabilities, deserves special attention. While research on the topic is still scant, its organizational impact within public entities must be highlighted . Indeed, GenAI can improve the performance of a range of language-based tasks that older algorithms tackle less successfully. LLMs excel at Natural Language Processing (NLP), an AI field that has been around for decades and which all three AI types have tackled in various ways. LLMs can generate new content, summarize existing content, translate and transform languages, develop computer code, perform on-demand data analytics, assist people with disabilities, and provide customer support. However, they do not cover the full range of possible AI applications.

However, GenAI can also impact how older AI algorithms perform and deliver — similarly to how AI has impacted older ICTs. That is a critical point, as digital public innovation should be seen more like a Matryoshka doll than a tabula rasa. In a nutshell, it comprises a set of nested innovation processes. Moreover, as a computational agent that can undertake various chores upon request and directly interacts with humans, GenAI is unique in that respect. It is no longer just another piece of software or hardware; it is a new, knowledgeable team member who could become its most important one. As such, organizational and process execution changes could be dramatic and entail a relatively high human cost—especially if algorithmic governance is permitted to hold the reins.

A vast literature on the governance of AI is already out there and is well-known . However, there is little on public-sector AI governance due to the lack of studies examining related AI investments. In any case, public sector AI governance has unique traits stemming from the fact that the public sector is distinct from others. The detailed public sector dynamics presented in the previous post should be a core part of the analysis if the goal is to discern the impact of public AI investments on public value generation.

The same can be said of AI in public-sector governance processes. AI to automate decision-making processes immediately introduces the perils of algorithmic governance which is essentially the result of the lack of having in place functional and binding AI governance instances and mechanisms. Again, the vast literature on the subject has paid little attention to the public sector, where algorithmic governance could have a nefarious impact on those negatively affected.

In sum, we have our work cut out for us.

Raul

References