Historically, the public sector has not been a leader in deploying digital technologies. In fact, it is usually a step or two behind other sectors, including civil society organizations. Reasons for such a predicament go beyond bureaucracy and, in numerous instances, are linked to legitimacy, transparency, and accountability. After all, spending public resources responsibly demands strategic thinking, especially in democratic regimes where stakeholders and non-state actors generally have plenty of leverage to push back or toward particular priorities. The now long, albeit patchy record of digital government (DG) provides a plethora of examples here.

The situation is precisely the same in the case of AI — old, resurrected, and resurging. In most of the academic literature, the public sector is chiefly considered a facilitator for developing national or sectoral AI policies or designing regulatory frameworks, which often faces strong pushback from those married to self-regulation . AI deployment in the sector has only recently garnered increased attention . In this light, revisiting the overall scope of the public sector’s core operations can help elucidate AI’s opportunities and challenges.

For starters, it is critical to consider the conceptual difference between state and government. Simplifying, modern nation-states are political entities operating within defined geographical borders, comprising a gamut of institutions operating within the framework of a social contract or constitution. A government consists of people who control, run, and manage state affairs for a given period and diffuse state power within its territory. The legislative and judicial branches of the state provide much-needed checks and balances to the government’s actions. In that context, the public sector refers to the state institutions mentioned above. Thus, Governments in power run and manage such institutions according to specific political agendas and alliances.

The public sector’s institutions, such as ministries and specialized agencies, have clearly defined mandates established by law and operate based on public resources the state captures via diverse mechanisms and manages following pre-established legal procedures . Note that public enterprises are also part of the public sector but operate on a profit-making basis. Thus, they are relatively independent of state finance and can cover areas beyond the public sector domain. Moreover, not all public institutions provide public services. Indeed, some are geared towards facilitating the operations of the state and the public sector.

Public entities’ legal mandates include the governance mechanisms through which those in charge make policy and public investment decisions, including discretionary powers they could use to change or eliminate specific governance instances. That is a critical point; in principle, any AI investment decision must navigate such waters safely. Thus, its deployments also depend on the power structures embedded within the political environment of the public sector.

The public sector has a wide range of tasks. According to the OECD , the sector has ten critical functions: 1. General public service. 2. Public order and safety. 3. Defense 4. Economic affairs. 5. Environmental protection. 6. Housing and community amenities. 7. Health. 8. Recreation, culture and religion. 9. Education. And 10. Social protection. It is, however, possible to aggregate such functions under six structural categories: 1. Infrastructural. 2. Economic. 3. Social. 4. Political. 5. Cultural. And 6. Environmental. In any case, such functions or structures make their social appearance via the delivery of public services.

Public services comprise a wide variety of services deployed in the public interest or for the public good with the support of governments. Services, including tangible products, can be directly provided by the public sector or indirectly by businesses and non-profit organizations, usually funded at least partially by governments . The provision of public services does not directly rely on markets or prices. Instead, it is determined by policy and political considerations. At some point, an entity or a group of individuals must use existing governance mechanisms embedded within the public institutions under their management to make such decisions. Therefore, knowing how decisions to allocate public resources are made is crucial from a governance perspective.

Unlike private services, public services have policy and political objectives and cater to stakeholders, not customers or shareholders. Moreover, stakeholders can simultaneously wear different hats—for example, they can be direct beneficiaries while participating in policy design, service provision implementation, and overall oversight. Their political nature allows countries to designate public services in different ways. For example, in many countries, health is usually a public service. However, others define it as private and thus implement it accordingly.

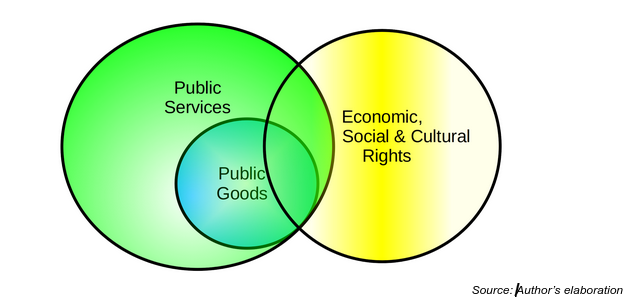

Public services are not identical to public goods. The mainstream definition of the latter stems from how access and consumption impact the good or service. Suppose access to a particular good is universal and cannot be limited in any way, and one individual’s consumption does not diminish its quantity for all others. In that case, the good is public. The best examples are national defense, knowledge, public broadcasting and Open Source software. While the traditional definition is still pervasive, the alternative of Global Public Goods might be more relevant for the Global South, including the option for countries to identify their own public goods . Again, governance structures play a fundamental role in such a process. Regardless, public services and goods are distinct; in principle, the public sector should provide both directly and indirectly.

Public services should also be framed within the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights , usually placed on the back burner when human rights are invoked to support long-term development interventions, including digital technologies. As in the case of public goods, the Covenant scope does not match public services one-to-one. However, it provides critical legal backup for governments to ensure economic, social and cultural rights linked to public services are on policy and political agendas.

The overlap between public services, public goods, and the Covenant’s scope should be the gold standard for policy and public service delivery. It should be considered a powerful magnet attracting other equally essential public or private services. The figure below depicts such an overlap.

Indeed, from a Global South perspective, linking public services to public goods and human rights can provide a grounded framework for prioritizing their provision while factoring in local context specificities, including the all-important governance structures and power distribution mechanisms.

I will examine state capacity and public value creation in the next post.

Raul

References