Is AI an ICT? It sounds like a straightforward question. But before we dive into those seemingly shallow waters, let us tackle acronym abuse. I hope to use four consistently: AI (Artificial Intelligence), Gen AI (Generative AI), IT (Information Technology), and ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies) – while adding a few more along the way. Historically, IT is the oldest. It saw the light of day in the 1940s when the first electronic (albeit analog ) computers emerged. Over a decade later, AI was born. Its history has been retold millions of times, so I do not need to repeat it here. Besides, I have already provided my own version. ICTs had to wait until the 1980s to enter the scene, while GenAI is still in its infancy in terms of years, but certainly not in terms of computing power and human-like skills.

Having a clear idea of what ICTs are before attempting to provide an answer seems prudent. However, that requires knowing what IT, the older but surely not wiser sibling, stands for. Simplifying, IT comprises the tools (software and applications) and infrastructure (hardware and networks) required to produce and distribute information within a given entity. The emphasis is on successfully managing such tools and infrastructure, not the actual content. An IT expert’s core job is to ensure that the information flows smoothly within a given domain on a 24/7 basis. The information produced by users is beyond her job description. ICTs are ITs on steroids as they add the telecommunications and media realms to their purview. Connectivity, internetworking and interactivity are thus core features. In that context, how users communicate and exchange information is central to ICT. In this event, it is now clear that IT is a subset of ICTs as tools and infrastructure are still much needed for its critical operations.

Needless to say, defining AI before we proceed is critical. As mentioned, agreement on an AI definition is still in the works. Having read my fair share of academic papers on AI and development, I have seen many use precious real estate to suggest one. I will have to do the same here—albeit my real estate is undoubtedly less valuable than theirs—for the time being. In a nutshell, AI’s primary focus is the creation and development of semi-autonomous computational agents that can successfully undertake a plethora of human activities. Achieving such a magnanimous goal demands access to sophisticated tools (AI algorithms and data management platforms) and infrastructure (computing power, reliable networks and storage capacity). Deep Learning (DL, another one of those!) and GenAI, in particular, are the most demanding. In that light, we conclude AI is part of the IT team. But at the same time, it is more than that, as we will see below.

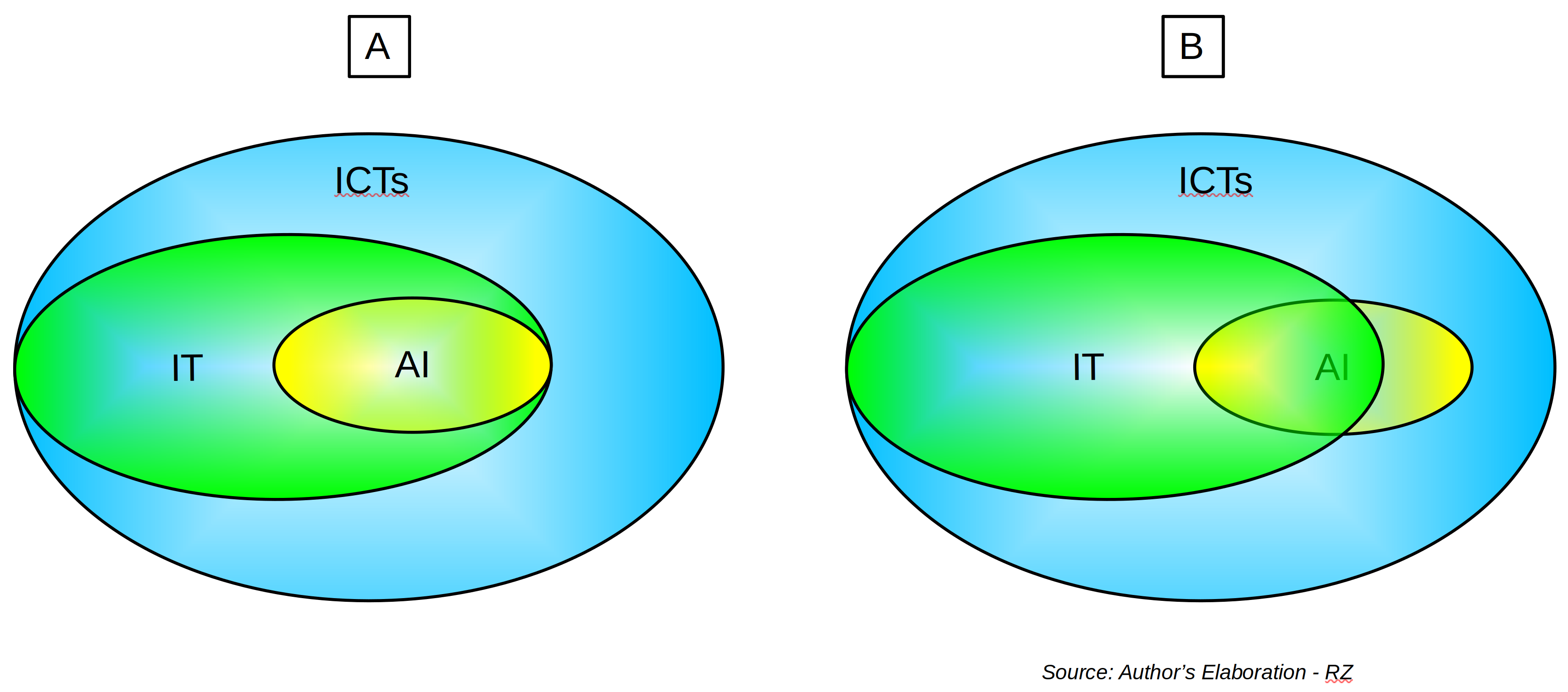

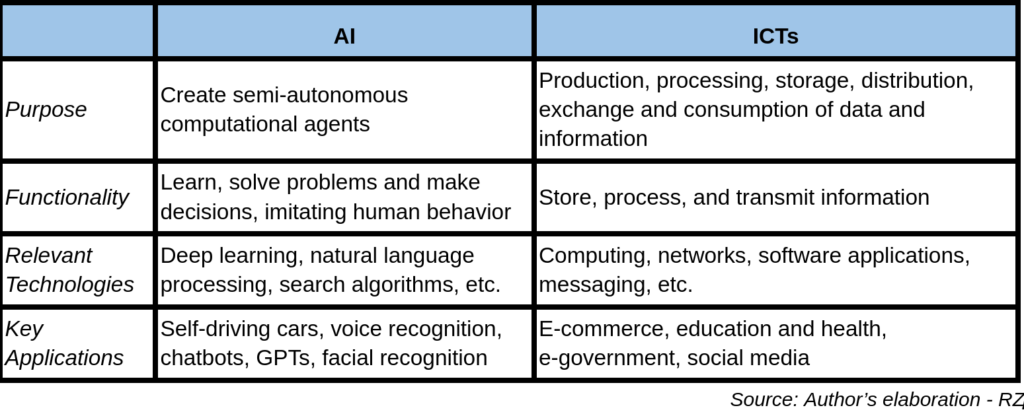

In any event, we can immediately conclude that AI is also part of the ICT team using good old Aristotelian logic (“AI is an IT; ICTs comprise IT; AI is thus an ICT”). However, we could depict these relationships using Venn diagrams in two ways, as shown below.

That’s right, AI is a movable target. In Exhibit A, AI is trapped within IT. However, in Exhibit B, much of its territory has migrated to the ICT domain. I will surmise that both are correct if we introduce the AI production process into the analysis. In the case of Good old-fashioned AI (GOFAI; addicted to acronyms!), AI seems to hit the target dead center. Not only were ICTs incipient at best back then, but the AI approach (also known as Symbolic AI) was following rules-based programming, similar to all other IT software and applications. Modern AI is a different beast, and its production relies heavily on ICTs. Consider areas such as data (big or not), data centers, internetworking, and so on. In fact, modern AI would not have been possible without the rapid development of ICTs on a global scale since the 1990s.

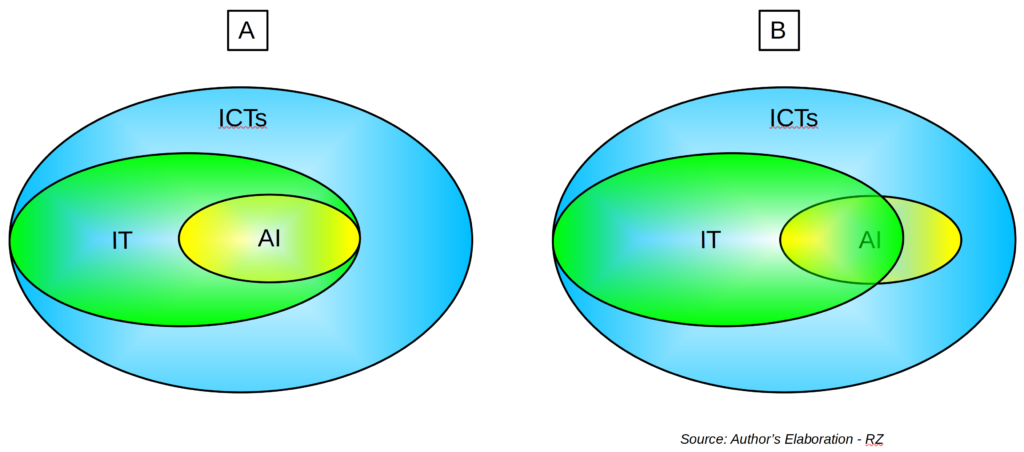

That said, we can now conclude that AI, old and new, is part of ICTs, albeit in varying degrees. However, that raises another question: What is the difference between ICTs and AI? The table below summarizes some critical differences, focusing only on modern AI.

Evidently, AI is a particular type of ICT that not only depends on them but, perhaps more importantly, its computational agents can dramatically transform them. Looking more closely, we can intuitively perceive how AI could change the functionality, technologies and applications that define ICTs. Indeed, modern AI can be used to optimize, automatize and increase the effectiveness of all ICT layers, from information production to critical public services such as education and health.

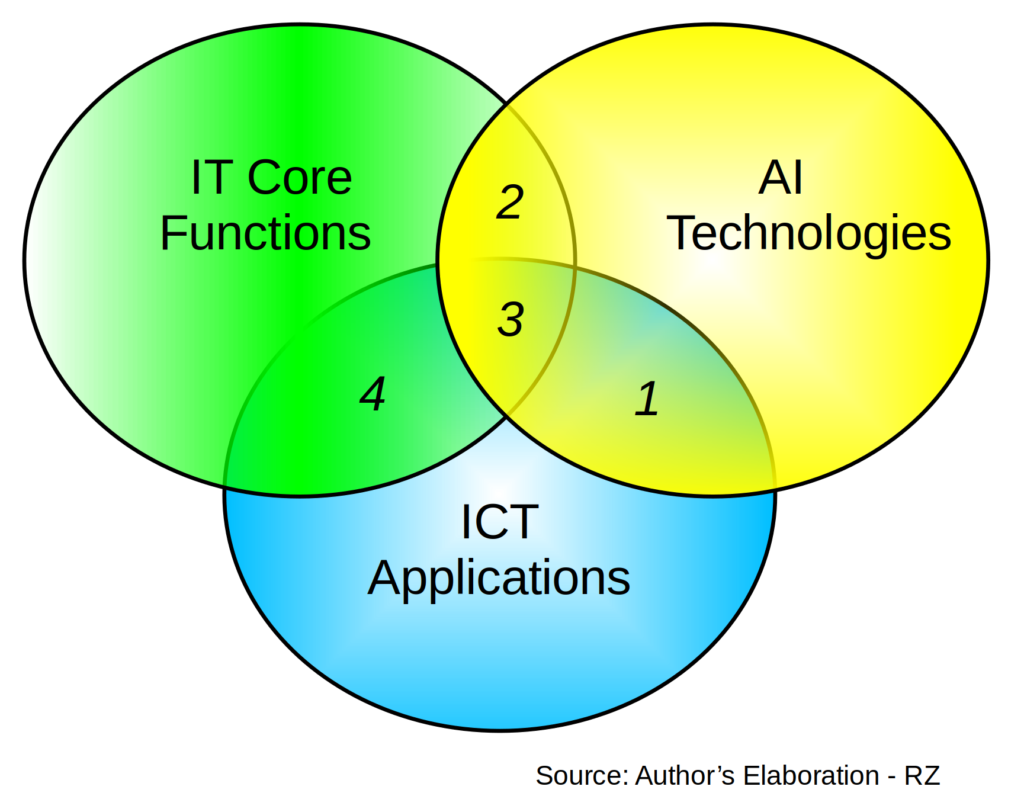

That suggests examining the interactive dynamics between IT, ICTs, and AI. The figure below depicts such dynamics.

For our purposes, intersections 1 through 3 are the most relevant, as they show AI’s impact on both IT and ICTs. First, AI can optimize and thus increase the efficiency of existing IT and ICTs. For example, deploying AI in data centers can reduce redundancies. In any case, further automation is the expected outcome here. Moreover, AI can also replace and thereby eliminate some of the older technologies and platforms. In addition, AI can transform their internal architecture by introducing new semi-autonomous capabilities. Finally, AI can augment its effectiveness by increasing scalability and reach in areas such as health and education. How deep can encroach into the other territories is a question that needs further research. We should expect the AI set to increase over time. At the same time, we should not expect AI to completely eliminate the other two. That could be suicidal, indeed.

GenAI provides perhaps the best example of AI’s limited ambitions vis-à-vis ICTs and IT. Its heavy dependence on ICT/IT tools, infrastructure and communications is undeniable. For example, data centers are now planning to expand capacity to cater to the demand for GenAI applications, regardless of their well-known environmental impact, which is much larger than just CO2 emissions. At the same time, data center managers are still skeptical about the potential use of AI for business management. Moreover, developing and training the most successful models depends on having access to sophisticated infrastructure and advanced computing power where GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) rule.

Perhaps much more relevant is the fact that GenAI can also directly impact older AI applications (but not older than 10/12 years!) in addition to IT and ICTs. It can then do to non-GenAI what the latter is doing to ICTs in general. The best example is chatbots, many of which were also deployed in the public sector. ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude, to name a few, are much more effective and powerful than any of the older versions of the technology. In principle, deploying them is relatively easy if we ignore privacy, confidentiality, and security issues.

In any event, the dynamics between all these technologies will become more complex in the short run. So we have our work cut out for us.

Raúl