The Development of Development

In its beginnings, unmovable numeric rankings permeated the always slippery and bumpy development racetrack. Stuck in first place were a selected group of countries labeled as developed, even though many were still rebuilding their economies after the bloody World War II that killed 3 percent of the world’s total population. Led by their own hegemon, they were also pressing hard to stop those immediately below from rising up. In second place was yet another selected set of countries claiming right and left to be “socialist,” trying to outcompete those on top by all means under the misguided leadership of their own hegemon. Caught in this unwavering rivalry, the rest of the rest comprising most nations, filled the last slot, agglutinated under the Third World hierarchical rubric.

Coined in the early 1950s, the Third World concept was shaped along the lines of the French Third Estate, which represented the Commons at the onset of the French Revolution and demanded the same rights as the other two, allegedly smarter estates, the clergy and the nobility. Similarly, and navigating the seas separating the two global hegemons, underdeveloped countries, as they were called then, had little voice in the proceedings despite a total population size that dwarfed the other two “worlds” put together as one for a change. Moreover, their engagement with the top tiers acquired a geopolitical flavor, thanks to the ensuing Cold War 1.0 that pressured countries to pick a side or else. Bandung was a partial reply to such demands and quickly led to the emergence of the Non-Aligned Movement. However, the latter did not include all developing countries as many, especially in Latin America, opted to support the First World’s hegemon. Indeed, there was never a unified Third World. And, in any case, the Third World moniker survived all these vicissitudes, regardless of geopolitical choice and the avatars of the Cold War.

The demise of the so-called socialist countries during the 1990s triggered an unexpected promotion for the Third World and finally ended its existence. The Global South, first used in the late 1960s, emerged as a suitable replacement together with its indispensable counterpart, the Global North. Binary thinking started to prevail. While some claimed these new categories were less hierarchical, it is critical to not lose track of the differences between geography, geopolitical positioning and socioeconomic development. For starters, no country can change its geographical location no matter how hard it tries. It is thus an immutable concept closely tied to Nature. That is certainly not the case with the other two. In principle, any nation should be able to opt for a specific geopolitical position and do its best to improve its inhabitants’ overall quality of life while preserving the environment, hopefully. As a result, the North-South divide cannot be reduced to geography or be associated with geopolitics automatically. While some might use the Brandt line to push such interpretations, that does not reflect the main thrust of the report published under his name.

Global North and Global South Dialectics

Indeed, consensus on the very nature of such a divide is not universal. Some might want to add the political dimension, human rights included. Others will push for a more nuanced developmental approach encompassing health, education, inclusion and social justice, thus transcending the economic realm that still dominates the alleged North-South division. The literature covering all these arguments is vast and should be consulted. Nevertheless, my main focus here is to explore the dynamics between the Global South and the Global North, regardless of how we specifically define such a distinction.

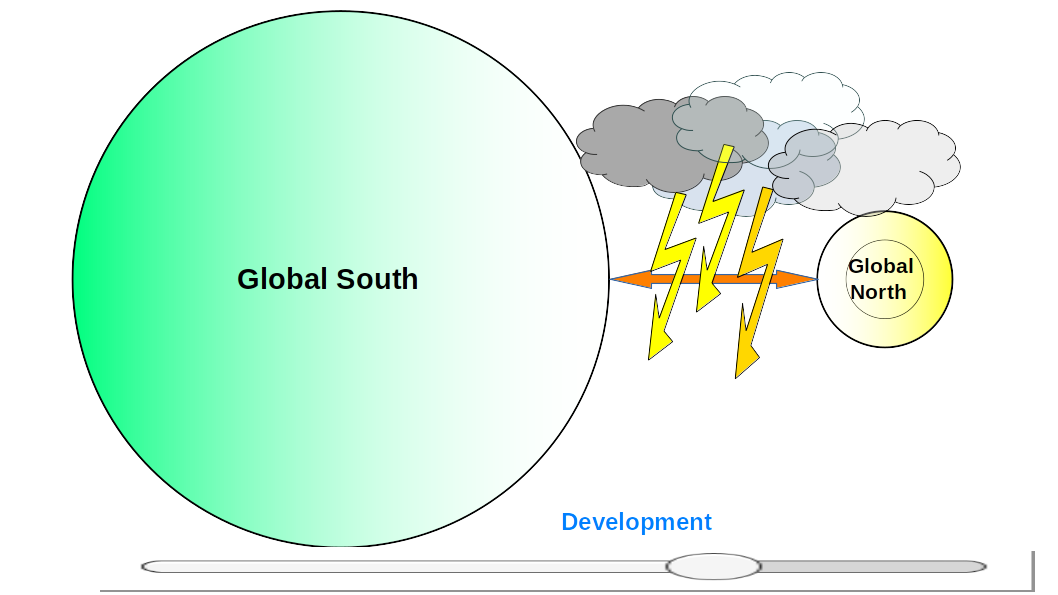

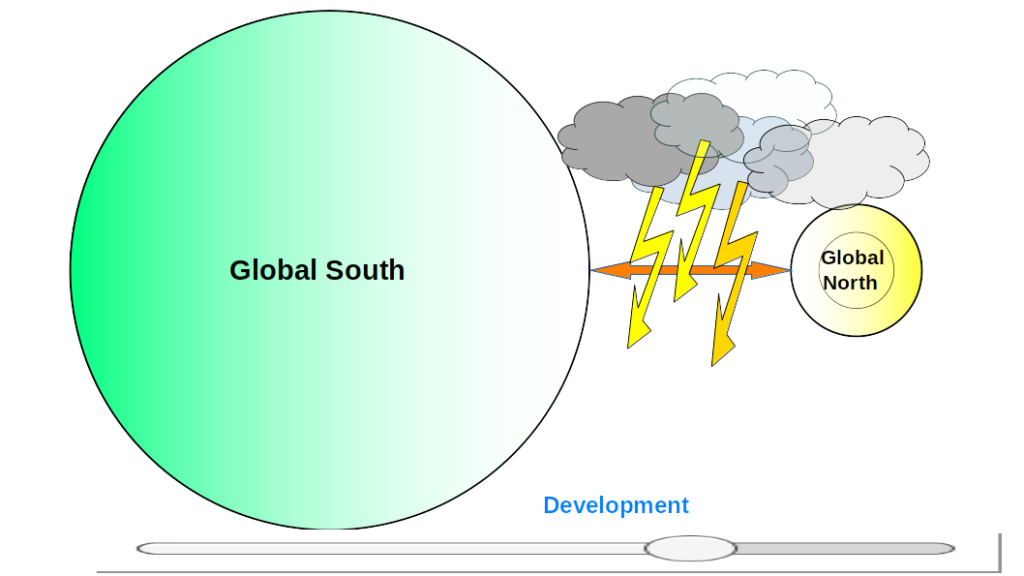

The first perspective here, and perhaps the most common until recently, is depicted in the figure above. Note that the bubble dimensions represent the population size of each camp nowadays. First, the two entities are sharp opposites, almost repelling each other. And moving from one to the other is very tricky, if not impossible. There is an intense and neverending hurricane one has to sort out to reach the other side. The development sliding bar can get stuck in the process and it is thus hard to move farther North. But once one reaches the much-sought North (alive, hopefully), it is also tough to go back – not that anyone is purposely trying to walk that path. Furthermore, both sides are relatively homogenous and thus usually treated as monoliths, sometimes allowing for minimal variations within. Interactions between the two sides are intense but traditionally seen as a zero-sum game where one side, the North, benefits from the other, leaving behind a few developmental breadcrumbs collected by the local elites for the most part. At this rate, the Global South will never be part of the Global North, nor has it been formally invited to join the exclusive club.

The 2008/09 Global Financial Crisis and the accelerated development of inequality in the Global North for the first time in a century started to challenge some core tenets of the above perspective. After all, developed nations also faced quite a few developmental challenges, the global hegemon included. However, I will argue that such challenges have been there all the time, conveniently disregarded by the powers that be and mainstream media, thanks in part to the Cold War 1.0 and the long tail of the “end of history” argument emerging after the end of the former. In any event, the differences between South and North are now blurry as several developing nations are already “emerging” while others have already graduated according to Nothern standards. Moreover, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have universal applicability, corroborate such an approach. The two sides entirely overlap in this view, so any separation is superficial at best. Granted, a few low-income countries (LICs) are still struggling, but it is just a matter of time before they start their inevitable ascend to the development heaven. In sum, this perspective is precisely the opposite of the abovementioned one. And a graph to depict it would add little as, after all, we are all in the same boat.

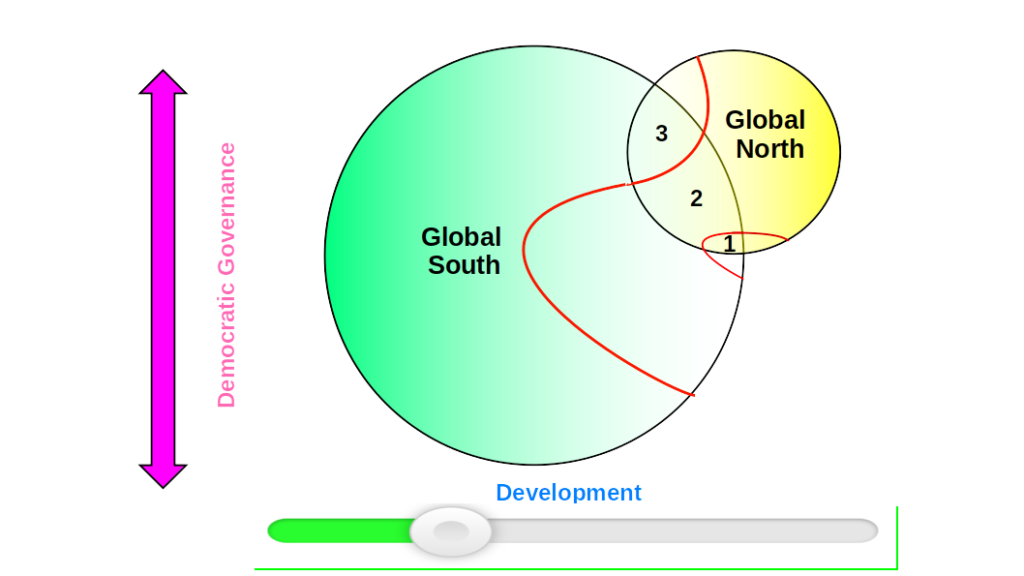

I will surmise these two seemingly antagonistic perspectives are limited and do not fully capture the complexities of development. Indeed, both include critical elements that must be interconnected to capture the dynamics of global development. Bringing them together, therefore, yields a much-improved framework. The figure below presents the results of such a merge. For the sake of presentation, bubble sizes do not match population size.

Indeed, the two sides overlap but only partially. First, its size is a function of the development dynamics driven chiefly by the Global North and, more recently, emerging giants such as China and India. Historically, it has increased thanks to the now infamous globalization process pushed big time by the North and its humongous private sector. It should also be clear here that we are talking about capitalist development that, in fact, can subsume non-capitalist regions under its aegis to expand markets and increase investment opportunities where profitable. Secondly, neither entity is monolithic. Rather, each comprises wide variations that depend on both the development sliding bar and the level of democratic governance (or lack thereof) advancement. A nation can be “democratic” but still lag big time in development terms, for example. On the other hand, a country can be a well-established member of the Global North but sliding down in democratic governance development. Uneven development is thus a common trait of capitalist development, regardless of team membership.

Third, the overall socioeconomic structures of each entity are strikingly different. In the Global North, the middle class (number 2 in the graph) is the largest. In contrast, the poor and marginalized (number 3) constitute the vast majority in the Global South, despite the relatively recent significant growth of its middle class driven by China, India, Brazil and other “emerging” developing countries. The ruling elites (number 1) are common to both but play different functions within each rubric, depending on the level of democratic governance development. Nevertheless, the ruling elites act in concert to secure financial support for implementing development policies in the Global South, designed mainly by the North, from Rostow’s “non-Communist Manifesto” and the Washington Consensus to the current global austerity dogma and its dire implications for the populations of both North and South.

This framework also allows for identifying development challenges within and between the two sides. The intersection between the two denotes the issues both sides share and where, for example, the SDGs could be helpful. But we can also see that the Global North has unique development gaps and would thus need special policy attention and social investment. The same goes for the Global South, with the difference that such unique developmental challenges affect most of the population. The SGDs might be useful in both cases if they can be appropriately localized and contextualized while specific development policies and investments find fiscal and political space.

Historical differences must also be accounted for. Many countries in the Global South were former colonies that slowly gained independence in the course of 150 years. Here we can find three cases. 1. Former colonies. 2. Countries or regions that were not directly colonized but were tightly linked to them for geographic or geopolitical reasons. And 3. Countries and regions of minor to no interest for the colonial powers and thus not exposed to capitalism early on. A common trait of the Global North is industrialization which started in the late 18th Century and peaked in the 1960s. Here we have two different situations. 1. Countries that experienced consistent industrialization process. And 2. Countries that did not directly industrialize but had strong backward and forward linkages to the former and were integral parts of expanding economic markets and regions. Much has been written about recent deindustrialization processes, which, in my view, have been greatly exaggerated. But perhaps the critical point here is that such countries will never slip back into “underdevelopment.”

In sum, the Global South has its own development dynamics like the Global North. However, to get an adequate global development perspective, we must combine the two and set them in motion. We can only capture the actual dynamics of global capitalist development in that fashion. The interaction of the two creates such a dynamic, while neither can exist without the other.

So whenever you run into yet another Global North vs. Global South discussion, keep all of the above in mind. After all, versus is only part of the whole story.

Raúl