While still prone to seemingly unpredictable dynamics, Bitcoin’s price seems to have found a new center of gravity in the last year. Since February 2021, the Cryptocurrency has oscillated around 4ok per unit, give or take. It peaked at 67.5k last November and then went down to 35k just a couple of months ago. At the moment (March 15), it is hovering around 41k. But the real big news of the last year has been the emergence of CryptoPopulism, spearheaded by the populist and authoritarian government of El Salvador. Copycats have already popped up all over the place, albeit much less successful on the P.R. front. Now even some U.S. states are considering similar policies. Confounding Crypto as legal tender and Crypto as a precious financial asset seems to be a typical pattern. Moreover, the business model undergirding such proposals is undoubtedly murky. But on the other hand, populists are not distracted by such petty nuances.

Being that as it may, the question I want to address here is the impact of these new developments on Bitcoin inequality, a topic I have previously explored. Based on existing U.S. income inequality research, I will be making the same assumptions as in my previous post (Bitcoin at 40K, one wallet, one user, three classes only, etc.). In Bitcoin, we cannot speak about income – except for the miners who get new Bitcoins and charge transaction fees when adding a new block to the chain). Here, wealth inequality seems a more appropriate term. We can dive into the most recent data pool with that in hand.

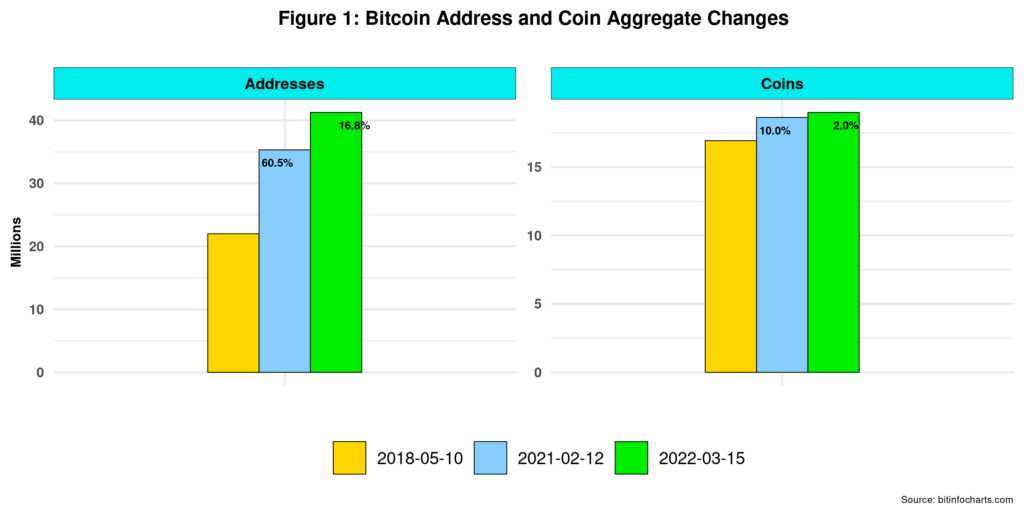

Figure one shows the overall aggregate changes. This time around, I have not included Bitcoin prices as they have changed little on average in the last 13 months.

As we know, the production of Bitcoins declines as the number of blocks increases and will stop for good once it reaches 21 million coins. So do not expect dramatic changes in its growth rates. As of today, we have 18.990 million Bitcoins inhabiting the digital realm. Address changes are a totally different story altogether. They grew almost 17% in the last 13 months, from 35.3 to 41.3 million. While undoubtedly significant, that number pales compared to Facebook users (over 2 billion) or people connected to the Internet (over 4 billion nowadays). Nevertheless, such growth shows increased interest in Bitcoin – as a scarce financial asset prone to high speculation, but not necessarily as preferred tender. The average number of Bitcoins per address or wallet is 0.46, equivalent to roughly 19k USD today. If Bitcoin were a country, the Word Bank would classify it as a high-income nation.

As we know, the production of Bitcoins declines as the number of blocks increases and will stop for good once it reaches 21 million coins. So do not expect dramatic changes in its growth rates. As of today, we have 18.990 million Bitcoins inhabiting the digital realm. Address changes are a totally different story altogether. They grew almost 17% in the last 13 months, from 35.3 to 41.3 million. While undoubtedly significant, that number pales compared to Facebook users (over 2 billion) or people connected to the Internet (over 4 billion nowadays). Nevertheless, such growth shows increased interest in Bitcoin – as a scarce financial asset prone to high speculation, but not necessarily as preferred tender. The average number of Bitcoins per address or wallet is 0.46, equivalent to roughly 19k USD today. If Bitcoin were a country, the Word Bank would classify it as a high-income nation.

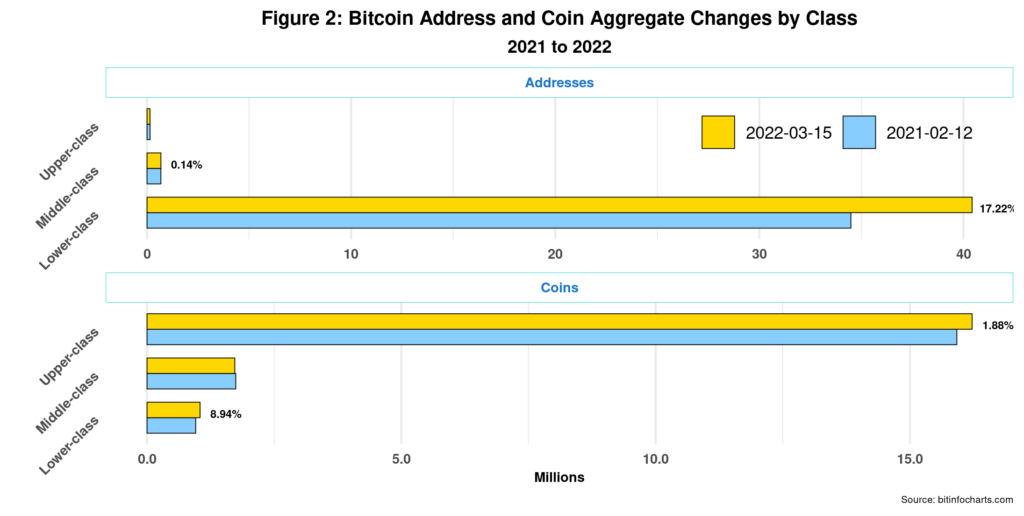

Figure 2 compares social class changes since last year. Again, the lower class (those holding 1 or less Bitcoin) has propelled the growth in addresses. This is because most new users enter the network at the lower levels of the social structure. Indeed, the absolute number of lower-class members increased from 34.5 to 40.4 million, out of 41.3 million total (98 percent!).

Changes in middle-class wallets were almost negligible, while the upper class (accounts holding 10 or more Bitcoins) experienced a decline of 2.1 percent, thus getting leaner (not sure if meaner, though). Economists have a name for such a process: concentration and centralization.

Changes in middle-class wallets were almost negligible, while the upper class (accounts holding 10 or more Bitcoins) experienced a decline of 2.1 percent, thus getting leaner (not sure if meaner, though). Economists have a name for such a process: concentration and centralization.

Coins experienced a similar pattern, with the lower class making the most significant gains overall, growing from 0.957 million to 1.04 million coins. While the middle-class lost some ground here (a 1.1 percent decline), upper-class holdings increased from 15.9 to 16.2 million. Note that for the lower class, address growth is much more significant than coin holdings, which translates into a reduction of almost 20 percent of the average coin holding per user. It now stands at 0.026 per wallet, nearly 40 percent below the average. If we check the U.S. 2021 poverty guidelines, Bitcon’s lower class would be covered. Bitcoin is then a high-income country with pervasive “poverty.”

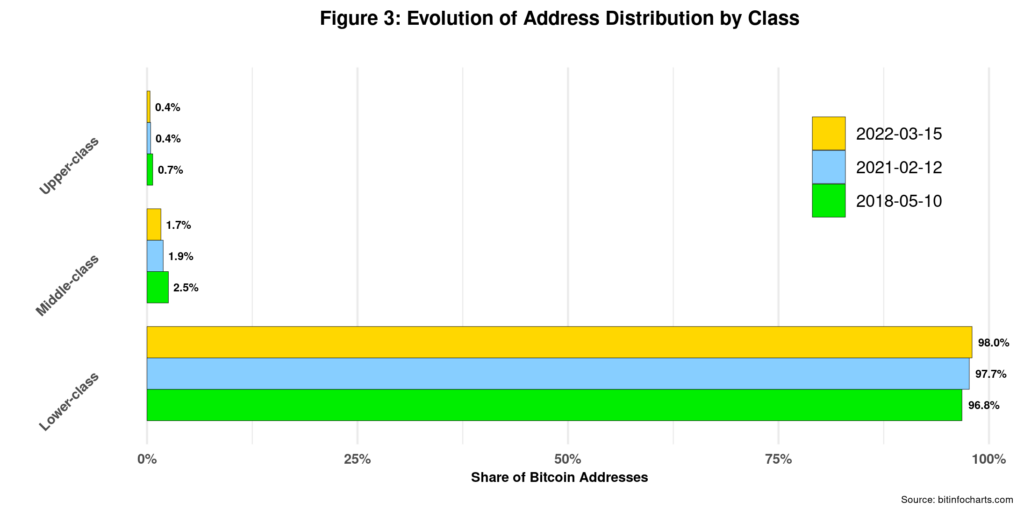

Figure 3 shows the changes in addresses by year and class. Again, the lower class is the only one reporting continuous growth, while the wealthiest class seems to be converging to a local and concentrated minimum.

Looking closer at the internal composition of the lower class, we note that while the number of addresses in its brackets (from 0.00001 and 1 Bitcoin) grew quite significantly, the lower rubrics experienced faster gains. That confirms that most new users are getting access via the lowest rubrics. The evolution of the various address balance brackets within the upper class denotes a particular trait. They all lost ground except for the 100k – 1 million coins bracket, which grew 33 percent. Actually, there are only four addresses in such a group. So a new billionaire has been crowned, joining the ranks of the 0.0000001 (1 x 10^-7, no typos here!) percent of Bitcoin’s population. The big loser in all this is the middle class that only recruited roughly 1,000 new members, thus feeling the pressure from both the top and bottom echelons.

Looking closer at the internal composition of the lower class, we note that while the number of addresses in its brackets (from 0.00001 and 1 Bitcoin) grew quite significantly, the lower rubrics experienced faster gains. That confirms that most new users are getting access via the lowest rubrics. The evolution of the various address balance brackets within the upper class denotes a particular trait. They all lost ground except for the 100k – 1 million coins bracket, which grew 33 percent. Actually, there are only four addresses in such a group. So a new billionaire has been crowned, joining the ranks of the 0.0000001 (1 x 10^-7, no typos here!) percent of Bitcoin’s population. The big loser in all this is the middle class that only recruited roughly 1,000 new members, thus feeling the pressure from both the top and bottom echelons.

People can join the Bitcoin nation in at least three ways. First, they can become miners and/or join a mining pool. While competition is tough and entry barriers are relatively high given hardware and energy requirements, expected profits are also very high. Successful mining nowadays means a reward of 6.25 Bitcoins or approximately 260k USD – plus transaction fees (currently at roughly 2 USD per transaction). Second, they can purchase Bitcoins via exchanges and so-called DeFi entities in the financial market. That is probably the path institutional investors take to put their hands on the “my precious” financial asset. That is also how El Salvador’s Government has been acquiring Bitcoins. And third, sellers of commodities and services that accept Bitcoin as a means of payment. Remember that the first Bitcoin commercial transaction occurred in 2010 when someone paid 10K Bitcoins for a pizza. Regardless, the growth in Bitcoin’s lower class population probably stems from options one and three.

Regardless, Bitcoin’s social structure resembles a developing country where the middle class is usually incipient. Instead, most people are sitting at the fat and ample bottom of the wealth pyramid. And those new members joining the economy can only do so at the lowest wealth levels, where they can remain trapped for life as upward social mobility is almost impossible given the high financial requirements. Bitcoin nation is thus a high-income developing country in terms of social structure.

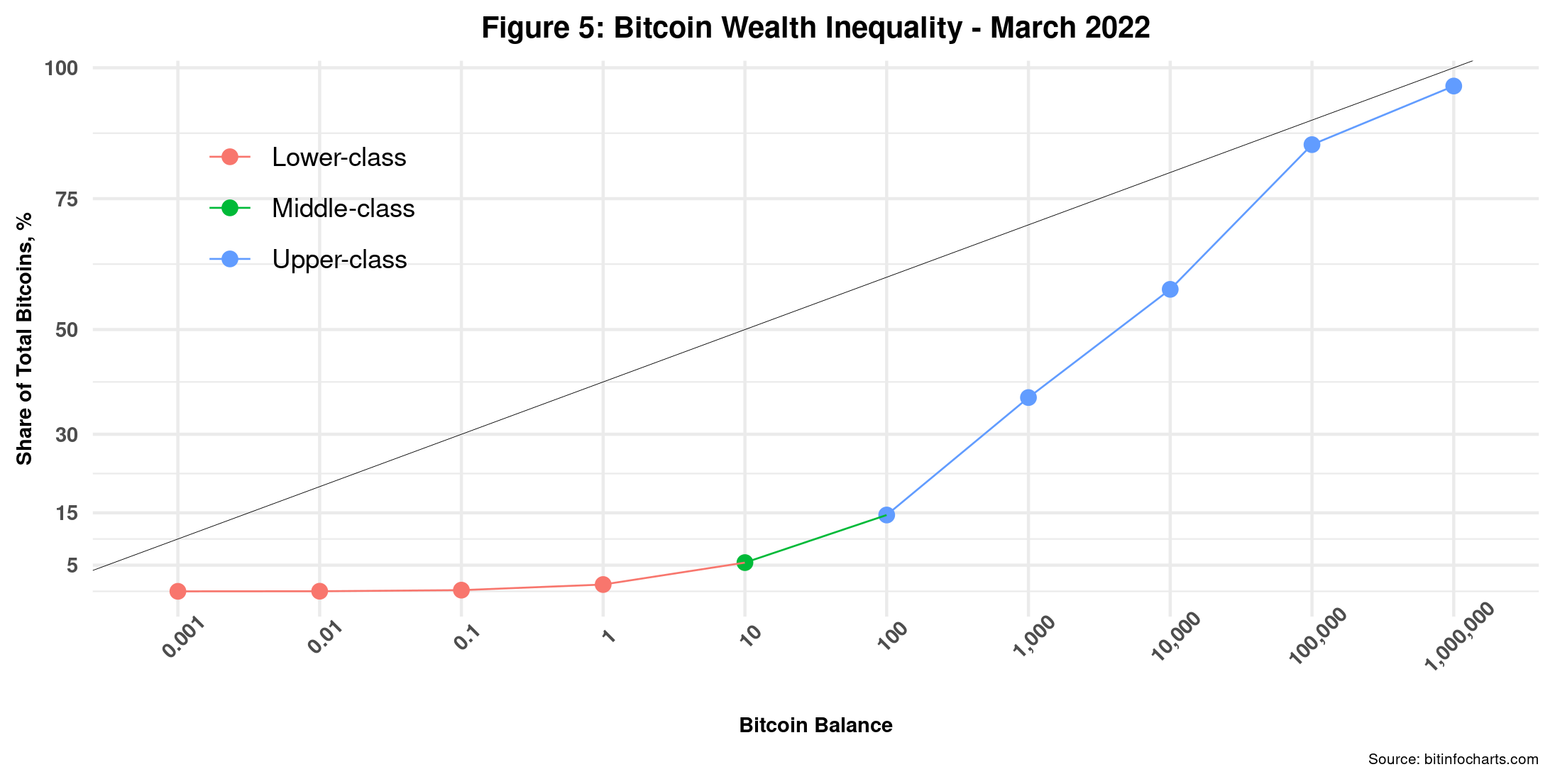

Figure 4 above is similar to the previous but details the evolution of Bitcoin shares by class. Here, we get an inverted wealth pyramid with the upper class occupying most of the Crypto territory, despite some relative losses since 2018. Bear in mind that a relative decline does not imply a reduction in absolute size on these graphs. It just says that other classes are changing faster. In 2022, both the upper and lower classes increased their Bitcoin holdings, the latter at a faster rate. The middle class experienced a relative and absolute wealth decline, thus confirming the squeeze mentioned above. No country for the Bitcoin middle class.

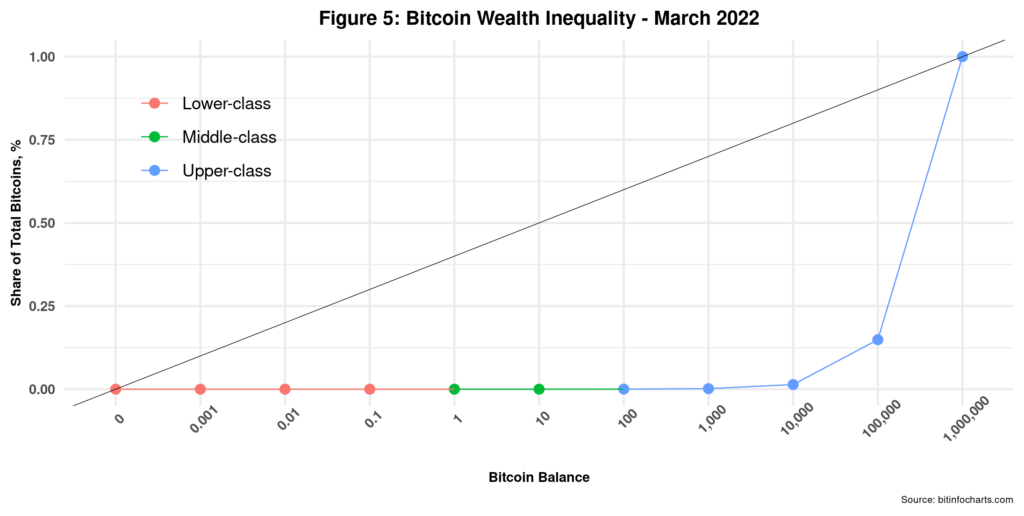

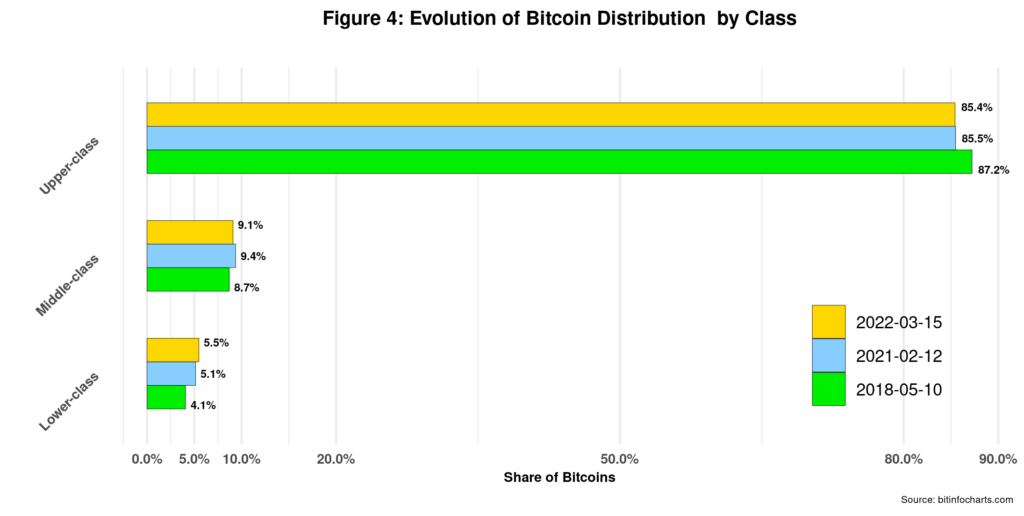

Comparing the two previous graphs allows us to see the contours of a very uneven distribution of wealth in Bitcoin nation. Here is where figure 5 below can be of most help.

I have reintroduced the balance brackets and drawn a 45-degree line that can be used as a reference to perceive the degree of inequality. In fact, this is the unweighted Lawrence curve. The lower class is the farthest from such a line, while the higher balance brackets of the upper class quickly pull towards it. But perhaps more revealing is the fact that the upper class owns over 97 percent of all Bitcoin wealth while representing only 0.4 percent of the total population. Compare that to the U.S. 2021 wealth distribution, where the top 10 percent of the population owned 70 percent of all wealth. Not even close. Bitcoin is the undisputable global inequality champion. Never mind Mr. Gini (close to 0.9 in Bitcoin nation). By the way, that is also the case for most other Cryptocurrencies. However, there is nothing in Bitcoin’s nature that propels such an uneven distribution of wealth.

I have reintroduced the balance brackets and drawn a 45-degree line that can be used as a reference to perceive the degree of inequality. In fact, this is the unweighted Lawrence curve. The lower class is the farthest from such a line, while the higher balance brackets of the upper class quickly pull towards it. But perhaps more revealing is the fact that the upper class owns over 97 percent of all Bitcoin wealth while representing only 0.4 percent of the total population. Compare that to the U.S. 2021 wealth distribution, where the top 10 percent of the population owned 70 percent of all wealth. Not even close. Bitcoin is the undisputable global inequality champion. Never mind Mr. Gini (close to 0.9 in Bitcoin nation). By the way, that is also the case for most other Cryptocurrencies. However, there is nothing in Bitcoin’s nature that propels such an uneven distribution of wealth.

In the end, it is essential to understand Bitcoin’s dynamic drivers. I have previously argued that the dialectics between Bitcoin as financial assets and Bitcoin as tender is one of the main engines of its peculiar evolution. I am sure its original creator would be bitterly disappointed to see how his beloved Cryptocurrency has essentially become an innovative Crypto asset that, in turn, has propelled the creation of many other digital financial assets – in addition to the emergence of many new Cryptocurrencies.

The financialization of the World Economy, which started in the 1980s, has played a crucial role here. It is now encroaching on many sectors of the economy and is calling the shots in many of them. Moreover, since the last Global Financial Crisis, Central Banks in developed countries have used Quantitative Easing (QE) to pump additional cash and capital into the global economy via private banks (securities) and national governments (bonds). So there is plenty of financial capital sitting around, looking for investment opportunities. And Information and Communications Technology (ICT) has been one of the best allies in these processes. Bitcoin first saw the light of day in such a speculative environment.

As a digital financial asset, Bitcoin’s price is determined by supply and demand, regardless of its intrinsic value – which could be zero. Large holders of Bitcoin thus play the financial speculation game, hoping its price goes up and up in the medium-term – which is what has happened so far. On the other hand, if the price is heading South, their best option is to weather the storm, buy more if they first purchased at a higher price or sell if they bought at a lower value. In all these scenarios, the incentive to use Bitcoin as tender is thus minimal simply because coin owners can lose money on the spot and/or forgo future profits. Therefore, bitcoin as a financial asset is the negation of its life as currency, as Hegel would say. That is why Bitcoin as a store of value, a vital function of any legal tender, is missing in action. Bitcoin price is all over the place, despite recent stability around 40k. That might change anytime. Here, uncertainty trumps risk.

Nevertheless, that does not entail that an interplay between its financial asset and currency personalities does not exist. On the contrary, Bitcoin owners are keen to promote it as legal tender as this might lead to price increases. Look at the support they have loudly provided to El Salvador’s adoption of Bitcoin as legal tender. Such a promotion is geared toward enticing third parties that have yet to join the network to use it primarily as a means of exchange. Having a central government saying that “all agents must be able to accept Bitcoin as a means of payment” does the job neatly – and legally. Recall that Bitcoin’s price went up at the time and reached its highest value ever soon after that. That strategy might also increase demand for Bitcoin as a financial asset, thus increasing its price. Such a strategy seems to be working for now, but it is probably unsustainable in the long run.

In any case, the real challenge for Bitcoin is to prove itself to be a reliable and efficient (speed, scale, convertibility) currency. If not, then another Cryptocurrency is needed. Meanwhile, Central Banks are already planning to issue Crypto versions of their national currencies, which, by definition, will be as stable as their fiat counterparts.

More turbulence is ahead, indeed.

Cheers, Raúl

Comments

One response to “More Bitcoin Inequality”