From Noise to Signal

A couple of weeks ago, El Salvador’s CryptoPopulist President shared on social media news about an international “Bitcoin” meeting his country was hosting starting May 16. He also listed the names of the 44 entities participating in the event. Not surprisingly, key countries were conspicuous by their absence. Regardless, the Crypto hype press machine soon started making the usual high-pitched white noise, glorifying not only Bitcoin for the billionth time but also their populist friend, now a global ambassador. Some even stated that the ambassador would show Central Bank representatives how to successfully adopt Bitcoin, modesty apart. Unfortunately, the actual history behind the meeting was lost in the shuffle.

The Alliance of Financial Inclusion (AFI) is a non-profit policy organization promoting what its name says. AFI members comprise Central Banks and other relevant financial regulatory institutions. The website shows AFI membership currently includes 101 institutions representing 89 countries. The meeting in El Salvador was the first in-person gathering after a two-year-plus hiatus due to the pandemic. It brought together AFI’s working groups on Digital Financial Services and Small and Medium Enterprise Finance. Co-hosted by El Salvador’s Central Bank, an AFI member since 2012, the meeting explored the potential merger between the two groups mentioned above. This goal makes a lot of sense in my view, as this is ICT for development (ICTD) deja vu all over again! And while the AFI members eventually visited El Zonte, the overall purpose of the official meeting was undoubtedly not Bitcoin per se. Instead, it was just another regular AFI meeting studying innovative ways to increase access to financial services by those at the base of the socio-economic pyramid. This target is at the core of its institutional mandate.

Financial Inclusion and Digital Divide

Financial inclusion is a relatively new term, albeit the reincarnation of older ones killed by failure and disruption (see below). Expectedly, it has become the target of many developmental initiatives and programs. Needless to say, the Bitcoin brotherhood (women being an absolute minority here) uses it all the time to justify any of its divine interventions, amen. Bitcoin’s raison d’etre is indeed financial inclusion, we are repeatedly reminded.

For those of us working in digital technology and development, financial inclusion is conceptually related to the so-called “digital divide” of the 90s—an idea that has somehow endured for almost 30 years. One big difference between the two is right in their names. While the digital divide highlights a gap —the haves vs. the have-nots —financial inclusion also points to an outcome from the very outset. Working on the latter thus has a predefined positive effect. I know exactly why I am doing that stuff. On the other hand, the result of closing the digital divide is still under much debate. There is no real consensus here, and deploying blockchain will not make a difference. Multiple outcomes are indeed possible here. However, no outcome is also a frequently seen option out there.

On the other hand, the two share a similar theory of change that can be summarized in simple terms. Closing such gaps will inevitably lead to socio-economic development. In previous posts and publications, I have highlighted this issue within the ICTD field. While we have many economic and social development theories, ICTD seems to fall short when it tries to link its practice to any of them. On the other hand, financial inclusion is closely linked to mainstream economic development theory and suggests that eradicating poverty sustainably requires expanding markets. Financial inclusion provides the poor with access to financial resources, enabling them to propel the expanding market. The picture is a bit more complicated, as digital technologies can indeed be used to promote access to financial services and resources. That is why the two AFI working groups are planning a merger. They are playing catch-up for sure.

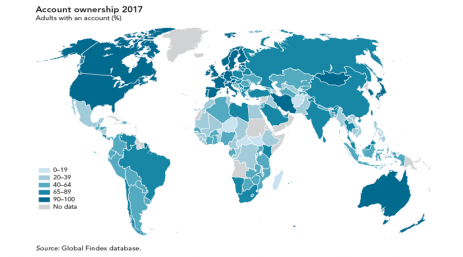

Their vanilla versions share a lot of ground by identifying access as the prime mover that can almost magically tear down most other socio-economic barriers. Give “them” an Internet connection or a bank account, and things will be cool. Provide both, and we are just a few millimeters away from the development nirvana. In any event, tackling access involves infrastructure investments of various degrees. In the case of the digital divide, that implies capital investments in backbone infrastructure and last-mile solutions. Once investments reach a certain level, relatively high costs become the main entry barrier for potential users with little income. On the other hand, financial inclusion infrastructure investments are fundamentally different and might require brick-and-mortar deployments to ensure physical access to branches and offices offering financial services. Here, digital technologies can make a difference, as physical access can be minimized as digital or mobile money spreads among disenfranchised populations. But once again, the main entry barrier is the cost of the network connection and the fees private entities charge for financial services. Regardless, such an example shows how digital technologies can amplify a given development target—financial inclusion, in this case —and thus seem to work best in such scenarios as an amplifier of that outcome.

Financial Inclusion Origins

A couple of years after Bangladesh became an independent nation, a young economics professor took his students on a field trip to visit a poor village. He discovered that the women producing bamboo stools were borrowing small amounts of money to support their operation but paying hefty interest rates. Their real income was thus minimal after paying all production costs and due interest. He then decided to use his money to support the women by charging them low-interest rates. Nine years later, he founded Grameen Bank (or village bank), which became one of the first financial institutions to offer microcredit to poor people. By the mid-1990s, Grameen Bank was also offering regular banking services to its poor clientele, thereby expanding into microfinance. And in 2006, its founder, Mohammed Yunis, and the Bank itself were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to promote social and economic development “from below.”

By then, his approach had already been replicated in over 50 countries, covering most regions of the globe. Grameen Bank’s potential impact on rapid poverty reduction, accompanied by substantial gains in education, health and women’s empowerment at the community level, was a mighty magnet. And still is today. However, current evidence suggests that such laudable impacts remain elusive. Still, I wonder if new technologies such as Crypto and its natural host, blockchain, could make a difference here, especially if the touted goal is to “bank the unbanked” already served by microfinance institutions. Statistically, at least, Grameen Bank beats Crypto by far.

Building on the successes and failures of microfinance efforts, financial inclusion began to gain traction at the end of the first decade of this century. It brought the whole gamut of financial services (equity, pensions, insurance, etc.) to the table. Furthermore, it enticed traditional financial institutions to partner with other entities, including microfinance institutions, and to cater to the poorest segments of the population. Indeed, financial inclusion is a target in eight of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It is broader than micro-finance and has now become one of the primary drivers of development interventions.

That is, in a nutshell, the mainstream history of financial inclusion. But this is not the whole story, as we will see in the next post.

Cheers, Raúl

Comments

One response to “Financial Inclusion and Democratizing Finance – I”