As mentioned in the previous post, policymakers should skip over the dominant technology-centered AI perspective and instead position AI as a multi-dimensional structure cutting across all sectors. Indeed, national AI policy effectiveness depends, to a large extent, on the AI vision that policymakers adopt. Unfortunately, AI appears almost irrelevant for many policymakers in low-income countries, given its complexity and the dire human development gaps they face. In a way, they are 100 percent right. However, they have yet to grasp how some AI applications could play a role in addressing such gaps. It’s definitely not a panacea, but it’s also not useless. They should be able to find the middle ground here. As a result, national AI policy development is not a priority in that group of countries.

For newbies and first-time boarders, AI appears as a series of complex computer algorithms that only the selected few can handle and understand. Furthermore, from the software side, AI seems tightly connected to Free/Open Source software (FOSS), as many existing algorithms and platforms are available on the open Internet. However, using them effectively is another story, as access to relevant data and advanced capabilities and skills are required. The latter helps to start unveiling the essential nature of AI.

AI Pillars

AI comprises three interrelated pillars, each simultaneously a dynamic, sophisticated engine on its own. They include

-

- Data. Big data, alongside data analytics, are the core component of this pillar. The lion’s share of most Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms depends on the availability of massive data. Let us not forget the usually disregarded data cleaning and labeling component that demands human intervention, especially for supervised learning algorithms. Data labeling has become a rewarding business, leading to the emergence of so-called ghostwork. Note that big data and data analytics predate the latest AI resurrection. In fact, they both played a fundamental role in bringing back AI from death.

- Digital infrastructure. Telecommunications, connectivity, hardware and software are core elements in this pillar. Being power-hungry, AI algorithms demand advanced computing power and hardware. In addition, cloud computing and state-of-the-art data centers with adequate storage, security, and reliable broadband Internet access should be in place. Ubiquitous connectivity on the ground complements the above to ensure datafication increases exponentially and data flows are non-stop. Finally, developing new AI algorithms and continuously refining older ones is the final stroke in the infrastructure picture. Once again, I need to point out that, except for the latter, all other pillar components were in place before the latest AI boom popped up.

- Human and institutional capacities. Talent, a capable workforce, innovation ecosystems and institutional capabilities are core team members here. Gaps in talent and workforce are expected, especially for AI algorithm processing and implementation. A local or national innovation network can help close such gaps, but it is critical for multidimensional AI development. Administrative and organizational capacities are also required to implement AI initiatives. Public institutions must be able to harness AI, and governments should be able to design and implement AI policies. Moreover, organizations and businesses (big and small) that fund and run AI initiatives are part and parcel of the AI equation. Finally, governance issues and power distribution among all stakeholders are critical components of this pillar.

The interconnections among these pillars are almost self-evident. Human agency and institutional mechanisms are the main drivers poking into data and digital infrastructure to achieve specific outputs, planned or not. At the same time, note that each pillar can exist independently and does not depend on AI. The causality line here is the reverse if we look at the process diachronically. AI rebirth is essentially the result of the evolution of pillars 1 and 2, thanks to the specific innovative agency within a given institutional environment by actors and organizations in pillar 3. However, as AI has gained vast territory, it is now imprinted on all three pillars, thus becoming the driving force. The child has grown into a gigantic adult and calls all others to submit. That confirms the actual multidimensional structure of the resurrected technology.

Policymakers should know the various pillars of the AI structure and their complex interrelations. These pillars can thus be defined as essential policy inputs that any national AI policy should factor in. The trick is to specify how such pillars work (or not) within a given national context and their interlinks with the global economy.

AI could trigger profound overall change, impacting most sectors of society in unexpected ways, so AI policies should not be limited to their technological impacts. At a minimum, they must be linked to national and international development agendas, existing digital policies, and national innovation systems. Academic research on AI policy development suggests that such policies should guarantee AI benefits spread evenly throughout society while closing glaring socio-economic and political gaps. Moreover, they should also reduce AI’s inherent risks, misuse, and potential geopolitical weaponization to a minimum.

Policy Dimensions

That opens the door for identifying critical areas AI public policies should address. They include the following policy dimensions.

- Socio-economic dimension. Comprises a mix of economic and social elements, including impact on local production, productivity changes, effects on existing comparative advantages, job creation and destruction, talent management, inequality reductions, promotion of social inclusion, better and improved public and private services, and augmented social cohesion. Note that these elements have close interconnections, so steering one in a given direction will necessarily move the others unintendedly if such linkages are ignored.

- Political dimension. Includes privacy, justice, ethics, human rights, trust, transparency, and accountability. Many of these themes have been on the digital policy development radar screen for over twenty years now. Therefore, it is required to take stock of their status before moving onto the AI minefield.

- Technological dimension. This dimension addresses AI limitations, safety, security, robustness, and explainability. While AI is more than another digital technology, ignoring its technical advantages and constraints is not part of sound policy development.

- Governance dimension. Includes the governance mechanisms that mediate stakeholders’ power distribution and interactions. Remember that the power distribution playing field is far from level. A few actors usually wield more power than the rest. Therefore, creating new or innovative governance mechanisms should be considered the starting point in any context. In principle, governance instances should ensure all local voices can be part and parcel of the AI policy development process.

The governance dimension has a unique character and central role in policy development. Firstly, it is both input and output. As the former, governance determines who can sit at the table before the agenda-setting policy phase commences – the contested place where critical areas must be identified and prioritized. Furthermore, it plays a fundamental role in the way the three other dimensions should be tackled. On the other hand, most policy development processes create governance mechanisms to oversee policy implementation and facilitate future monitoring and evaluation. Thus, the governance dimension is critical to ensure that technology-centered perspectives do not overwhelm the policy agenda.

Policy Framework

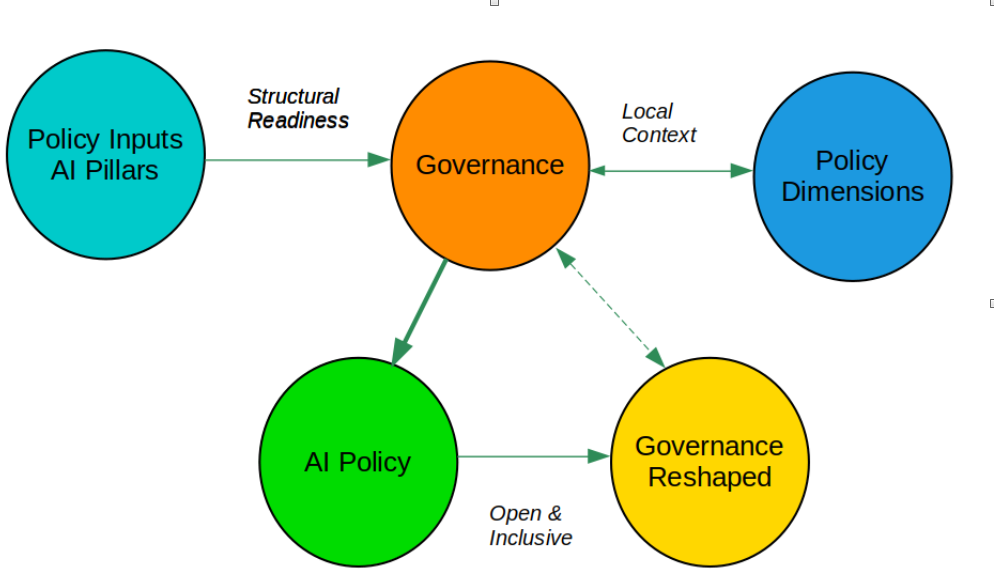

Linking the AI policy inputs with the above dimensions yields a comprehensive framework for studying AI policy development. Countries should determine their stand concerning the sophisticated AI multidimensional structure summarized by the policy inputs described above. Overall readiness (or lack thereof) is thus of paramount importance. Second, the four policy dimensions and their components comprehensively capture the local context. Indeed, they set the overall environment for developing a national AI agenda with clearly defined priorities. In principle, such critical areas should be interlinked and sequenced accordingly during the policy design process. Note that policy inputs and dimensions demand a wide range of expertise that should be readily available in principle. A multidisciplinary approach is best, and many countries already have expertise in core development areas. Additional AI expertise must be nurtured locally or imported in the short term.

The figure below depicts the policy framework.

In the next post, I will use this framework to review the status of AI policy development worldwide.

Cheers, Raúl

Comments

One response to “AI National Policies – II”