The road that took me to Hegel was long and winding—to almost paraphrase the Beatles’ last album song. I first spent two-plus years studying engineering, trying to tame incommensurable, difficult-to-digest content under the headings of calculus, advanced mathematics, statistics, and physics. Sleeping was a luxury while staying alive was the goal, pace The Bee Gees. Stuff like polar coordinates, Taylor Series et al., non-linear differential equations, numerical methods, Einstein’s Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, among others, were part of an otherwise convoluted scene.

I must admit I learned a lot and particularly enjoyed physics, which I have been following since. What finally broke my (Hegelian?) spirit was Statics. I could not see myself spending days or weeks calculating the structures needed to design a stable, resilient bridge. How could that be fun? I painfully discovered engineering was not my thing. Almost on a whim, I decided to switch to sociology, its antithesis, according to my intuitive understanding—its negation, in Hegelian speak.

A subtle and almost imperceptible helping hand popped up from the most unexpected source. The engineering curricula required us to take non-technical courses to enhance our obviously limited knowledge frontier. Philosophy and World History were among the choices. I first opted for a class on the Renaissance, rather than Greek philosophy. I have heard quite a bit about the latter but did not know much about the former. Furthermore, I was very curious about what was resurrected then. I got hooked right after the first class, as the professor, Ramón Pérez Mantilla, a local philosopher, was beyond brilliant. How can someone know so much? I asked myself. His lectures were the absolute negation of boring. Indeed, I felt like watching a historical film where all the macro action was enhanced and refined with hundreds of tiny details that dynamized the story ad infinitum.

He recommended Jacob Burckhardt’s classic text and Alfred von Martin’s short book Sociology of the Renaissance, recently reprinted by Routledge. So there you go. My small library still holds these two books I bought over 50 years ago. Needless to say, Professor Pérez Mantilla went well beyond these texts in his very entertaining and inquisitive lectures. The following year, I opted for a class on the Enlightenment, taught by the same professor, yielding the same fantastic results. Philosophers from Picco della Mirandola and Machiavelli to Descartes, Diderot, and Vico became intellectual acquaintances. The latter deserves additional credit, as he was one of the first Enlightenment critics, thus beating Adorno and Horkheimer by two centuries, as they duly acknowledged.

Once I switched to sociology, despite my father’s open yet subdued disagreement, the road’s final stretch was a relatively more straightforward walk—or read. However, getting my eager hands on a Hegel book still required me to follow the academic curriculum. I first had to dive into the works of Machiavelli, Moore, Bacon, Descartes, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant. That took a few semesters. It was fun and enriching, unlike the tedious calculations for bridge structure design. I was more than confident I had made the right decision after all. Succinctly, I was unimpressed by the British empiricists and thought Kant did well putting them in their proper place.

I finally got to Hegel via his Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences, the text that the philosophy professor, a Jesuit who had studied in Germany, recommended. He was another great professor, but sadly, I do not recall his name. I still have the hardcover edition I bought back then and dust it off frequently. Hegel was undoubtedly not a poet. His writing style is indeed complex and demands lots of attention. I have read him in two languages (albeit not German, unfortunately), and the language complexity survives translations. In any case, I believe the two-plus years I spent serving my self-imposed hard-core mathematics sentence in the engineering jail helped me conquer such treacherous grounds.

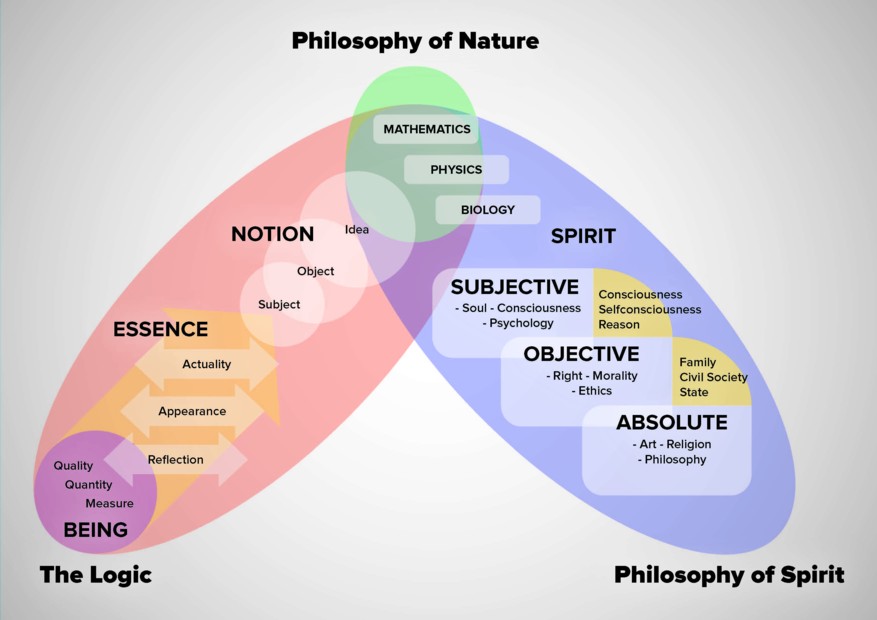

The main challenge in reading the German philosopher stems from his methodology, which differs from that of most previous philosophers: his dialectical method. Grasping it from the onset is thus fundamental. Looking at the table of contents of the Encyclopedia or the Science of Logic, for example, we quickly see a pattern where triads dominate the proceedings, and many are nested. Furthermore, everything seems to be connected and in motion simultaneously. In my view, that is the real challenge. Our Hegel professor spent the first few lectures on the Encyclopedia’s first part, the Science of Logic. I now understand the reasons for such an approach. That, however, can quickly become a chicken-and-egg issue, as one needs to distill the logic from the reading while simultaneously applying it to grasp the content in full. No one said it was going to be easy. By the way, Martin Hägglund’s This Life and Nancy Fraser’s Cannibal Capitalism implicitly use the same logic. And both are certainly very readable.

The text most relevant to my purposes here, Philosophy of History (PoH), follows the same logic, although it has four main parts. But each has three sections, and some are divided into three subsections. However, we are first and foremost interested in its contents. While Hegel’s text is perhaps the most comprehensive, Vico, that gentleman again, can be considered the field’s founding father. Research on the relationship between Vico and Hegel is available and should be consulted by those interested. That said, the language in Hegel’s ambitious undertaking is much simpler than in the texts mentioned earlier. That can be explained by the fact that the book is a compilation of his Berlin lecture notes, published only after his death. As a result, one can pick up the book and read it without first delving into the logic or phenomenology.

Reading the lengthy PoH introduction is a much-needed step. Hegel uses such real estate to present his views on history, summarize part of his philosophy, with emphasis on the Spirit triad, and share a geographical division of the world according to the Spirit’s developmental levels. I suggest paying particular attention to his idea of universal history, which is also presented in the Encyclopedia. The latter section is perhaps the most shocking and has, as expected, become an easy target for both friendly and unfriendly critics.

Hegel divides the world into new (the Americas) and old. While he praises the evolution of North America and claims it represents the “land of the future,” he proceeds to exclude the whole region from “universal history.” He then turns to the Old World, which he divides into Africa, Asia, and Europe. He dispatches Africa unceremoniously (“For it is no historical part of the World; it has no movement or development to exhibit.”) and argues that Asia is where the “Light of Spirit” arose for the first time. The world’s history thus travels from East to West “for Europe is absolutely the end of History, Asia the beginning … for although the Earth forms a sphere, History performs no circle round it, but has on the contrary a determinate East, viz., Asia.” The result is a teleological universal history that excludes a large portion of humanity by default.

I will argue that such views were pervasive in Western philosophy then—and still thrive in some quarters today. A good example is John Locke, the alleged father of liberalism. His views on Native Americans and the supposed “benefits” of settler colonialism fit perfectly into Hegel’s PoH. Locke, a staunch defender of private property, argued that expropriation, removal and ensuing oppression of Indigenous populations was fair game, given their “state of nature” (Hegel’s Spirit) and absence of political institutions (the state, for Hegel). That is certainly a far cry from good old liberalism. While Locke was a century younger than Hegel, the real difference between the two is that Locke’s home country had already embraced settler colonialism during his lifetime. On the other hand, Hegel’s nation, Prussia, was a relatively passive actor in such a devastating arena and did not become a colonial power for 40 years after his death. Locke was thus an active participant, while Hegel was a creative observer.

Not surprisingly, references to colonialism as a process in PoH are few and far between. My PoH English version has over 20 relevant mentions, but most address Greek and Roman colonies. So we have to look elsewhere. Fortunately, a recent academic article takes the issue head-on. The author reviews various of Hegel’s writings, including some that are still unavailable in English. She concludes that Hegel primarily saw colonialism as a necessary but insufficient solution to the critical dialectical contradictions between civil society and the state. That immediately reminded me of Rosa Luxemburg’s take on the subject that led her to actively oppose colonialism and militarism. Unfortunately, such a connection is missing in the article.

Instead, the article ponders Hegel’s relevance for postcolonial and decolonial studies. Of course, there are two opposing camps here, one being the negation of the other, to stick to Hegelian language. In one corner, those who call for him to be dismissed entirely, given his apparent support of colonization. Conversely, those who argue that Hegel’s attempt at creating a “universal history” from a philosophical perspective, alongside Vico, should be considered forward-looking and a game-changer in the field. The way the article resolves this contradiction is unsatisfactory, as the author seems to push for both at once. No need for Hegelian sublation here, apparently.

I was really impressed by PoH the first time I read it. It is a brilliant yet seriously flawed attempt to create a universal history. While I am certainly not a Hegel expert, I sympathize with the friendly view. Suppose the article is right about Hegel’s views on colonization. In that case, Luxemburg must enter the fray, opening the door to other schools of thought dealing with the topic from an emancipatory perspective. That sounds very promising, indeed.

What we really require, then, is a pluriversal world history without any “determinate” geographical reference. Curiously, many of these authors remain oblivious that such history has already been written, not yesterday, not last year, but over twenty years ago. Its author is Enrique Dussel, and his vast oeuvre, rivaling Hegel’s, speaks for itself. No wonder, then, why some call him the “Hegel of Coyoacán,” a geography Hegel dismissed as follows: “Of America and its grade of civilization, especially in Mexico and Peru, we have information, but it imports nothing more than that this culture was an entirely national one, which must expire as soon as Spirit approached it. America has always shown itself physically and psychically powerless and still shows itself so. For the aborigines, after the landing of the Europeans in America, gradually vanished at the breath of European activity.”

We already have a decolonial Hegel—spread the word throughout the pluriverse. And yes, “Spirit” eventually arrived, but not in the way the German philosopher predicted—not even close.

Raúl