By all accounts, the regulatory tide, constantly receding for so many years, is finally returning to the digital realm’s now extensive and arid shores . Indeed, digital platforms are now under the policy microscope, especially the well-known global giants whose names I do not need to echo here. These behemoths are carrying the day with little sweat, thanks to their innumerable and yet tenaciously robust tentacles reaching most, if not all, corners of the globe while encountering little resistance and certainly no competition. They are undoubtedly hosting a billionaires-only ball, with invitations going to a few selected. I certainly did not get one, but I was not expecting otherwise. In any event, I do not like to attend such frugal festivities.

Regulation, a dirty word in many circles and several countries, has been conspicuously absent from the digital domain. The most usual and almost immediate response used to justify such a glaring lack of action is that it kills innovation, period. Never mind that such an alleged fact cannot be corroborated historically . At any rate, researchers have identified three digital domain regulatory stages , the first commencing around 1998 when the Internet was still in its infancy and most countries were not yet connected to the emerging internetwork. Yes, there was not much to regulate. The nascent digital space was a “free for all,” awaiting to be conquered by digital versions of pilgrims and conquistadores alike. It was still a heavily decentralized space where those attempting to control it were public enemies lacking any understanding of how the new, open, infinite space worked. In other words, old farts with tiny brains. Cyberspace was a free territory that had its own Declaration of Independence. And it was propelled by unique dynamics that did not require government intervention or regulation .

Ten years later, the situation was dramatically different, thanks mainly to the emergence of social media platforms that began to enclose the previously open and free digital space, centralizing resources, networks, data, information, and users. Cyberspace was starting to look like the old analog world of the 20th century. Nevertheless, its modus operandi was substantially different due to its digital nature and the much-touted “network effects” . Self-regulation was the only way forward, as platform owners and managers were the only ones capable of really understanding how the new digital economy worked . For the rest of us, ignorance was instant bliss.

The third phase started in 2019 when policymakers and regulators finally acknowledged that the new giants had become economically and politically powerful and thus needed to be tamed. The question was no longer “if,” but “how.” Here, the European Union (EU) took the regulatory lead , building on the relative success of the GDPR, approved in 2016 and enacted in 2018. By 2022, the EU had already agreed on two core regulatory policies, the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA), both razor-focused on digital platforms. These policies will fully expand their regulatory wings next year. Other countries, such as Australia, Canada, China, India and the UK have followed suit with similar and complementary legislation. In the US, at least seven draft bills targeting platforms have been submitted to Congress. Approval, however, seems unlikely, given the current political context. In any event, welcome to the age of digital platform regulation .

Note that these new legislations target digital platforms, not the overall digital space. In that light, ensuring we understand what kind of beast a digital platform is seems absolutely critical, especially if we are going to use the digital lash to tame it. However, here we start to swim in murkier waters, as conceptual agreement, academic and otherwise, is still in the works. A recent review uncovered well over 15 different platform definitions, ranging from matchmakers to sophisticated technological systems—with one author even suggesting that platforms do not exist . One of the best-known books on the topic suggests platforms are characterized by new business models that bring groups of people together. Note that its author was directly involved in the EU platform regulatory process. In any event, his initial definition of platforms needs an additional turn of the screw.

One way out of the platform conceptual swamp is to step back from the digital domain and examine the economics of platforms in general. Here, the idea of two-sided markets can be beneficial as it immediately introduces the concept of intermediaries, which the original Internet was supposed to eliminate once and for all. In a previous post, I showcased the three types of intermediaries one can run into. In theory, intermediaries that benefit from network effects operate on two-sided markets. That is, they directly connect businesses and consumers by bringing benefits to both while allowing differential costs and prices on each side. Credit cards are a classic example. I can get one of those plastic cards, perhaps without paying an annual fee, and use it at any business in the same network. If I fail to pay my monthly balance in full, I will be assessed a late penalty fee, plus interest, usually ten times the official rate. On the other hand, businesses are charged between 1 and 3 percent per transaction, which they can pass on to consumers, but they get more customers who can now use credit to buy things and pay later. That is indeed a new business model that brings groups of people together—and one that traditional intermediaries lacked. Note that the digital domain has yet to enter the scene.

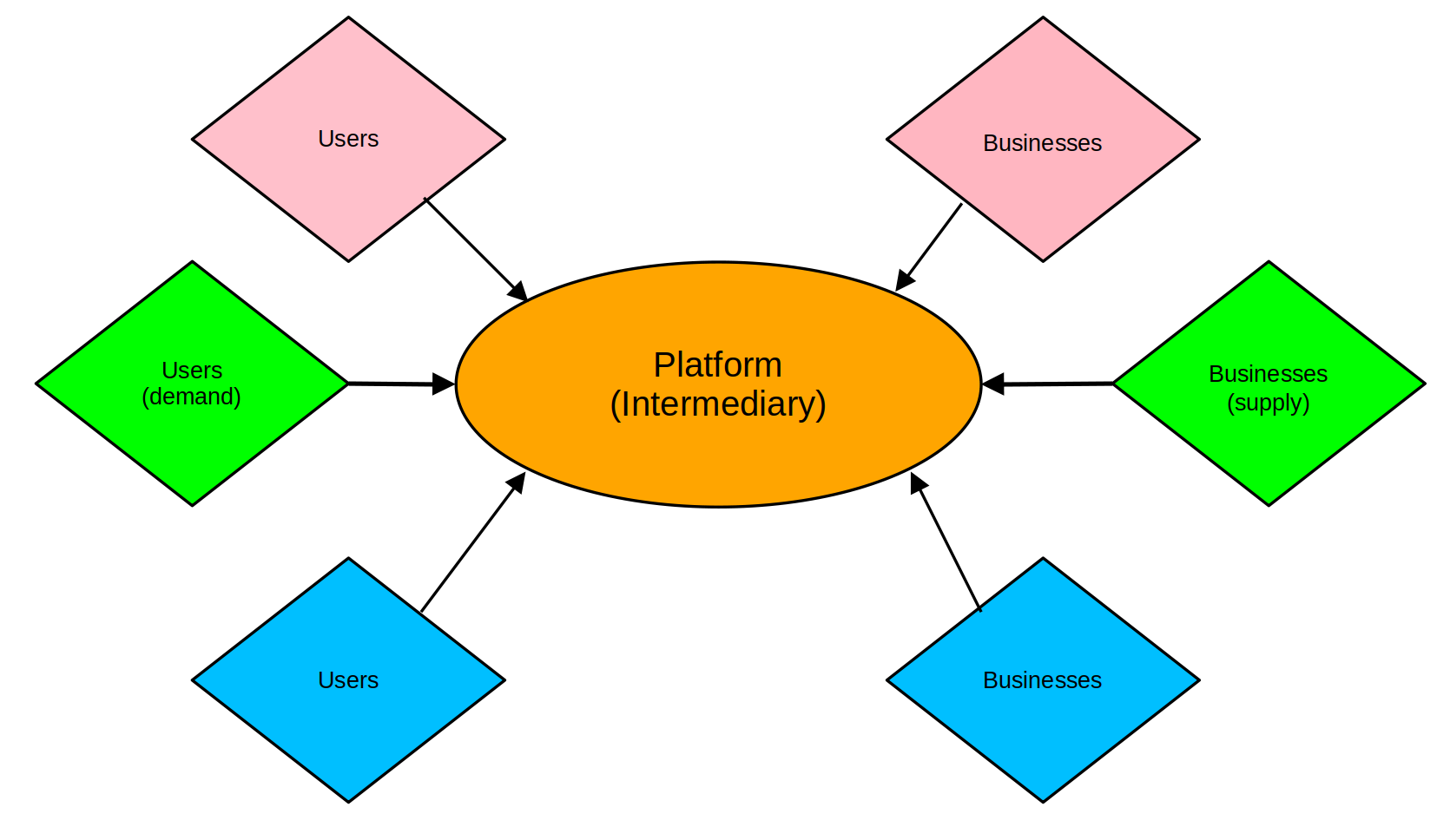

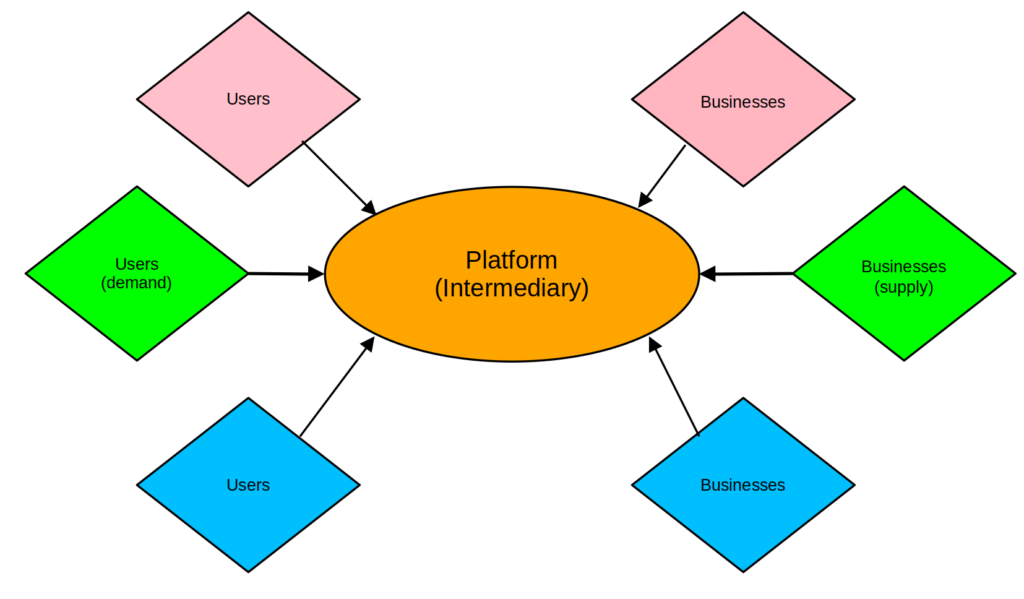

So what happens when we bring it in? At least three new elements emerged. For starters, businesses and consumers are forced to quit the analog world and migrate to the digital domain, where the new digital intermediaries make their living. That implies that digital platforms must create and provide access to software tools, networking channels, and mechanisms that allow users to interact effectively. My plastic credit card is useless if intermediaries do not allow me to use it securely online. Second, digital platforms can operate simultaneously in multiple two-sided markets, unlike poor credit card issuers stuck to just one—but they can still make super profits. Indeed, digital intermediaries are multisided platforms . If in doubt, take a quick glance at the digital behemoths. They resemble hydras popping up everywhere. That is a crucial regulatory issue, as policymakers should not directly target specific companies but rather the markets and sectors in which they operate. Last but not least, digital platforms disintermediate analog two-sided markets by shifting the playing field to a new domain under their full control, centralizing resources, and creating new digital intermediaries. The figure below depicts a multisided digital platform operating in three two-sided markets.

Moreover, unlike analog platforms, users and businesses must always be within the platform’s digital space and thus have the capability and means to access it. Another unique trait of digital platforms is the cost of switching between them. Platform interoperability is not one of its features, a fact that should immediately attract the attention of regulators.

Moreover, unlike analog platforms, users and businesses must always be within the platform’s digital space and thus have the capability and means to access it. Another unique trait of digital platforms is the cost of switching between them. Platform interoperability is not one of its features, a fact that should immediately attract the attention of regulators.

All in all, digital platforms are an exceptional case of traditional two-sided markets. And while they indeed have a new business model connecting groups of people, that is not enough to capture their actual specificities.

And yet, not all digital platforms are the same. I will look into that in the next post.

Raúl

References