First published in 2017, Stanford’s AI Index Report provides extensive AI information covering a wide range of topics. Take no prisoners seems to be its implicit motto. The latest 2024 version is the most voluminous yet, with over 450 pages. Areas such as the economy, health, policy and governance, and diversity are part of the proceedings. However, an AI index that ranks countries accordingly is not part of its many outputs. That said, responsible AI (RAI) quickly gets its chapter. RAI is delimited to privacy, data governance, transparency, explainability, security and safety, fairness, and electoral processes here. Working with Accenture, the report conducted a “global” RAI survey comprising almost 16,000 responses covering 19 industries and 22 countries (that’s why global is in quotes!). Country names and selection criteria are not spelled out in the final document.

Developing AI indices in the age of big and mega data is a core staple. I have previously reviewed two such efforts that, unlike Stanford’s, did not survive the implacable advance of AI and its noisy accomplices. The latest attempt arrived under the guise of the Global Index on Responsible AI (GIRAI) just over a month ago. The project received financial support from the Government of Canada, USAID, and IDRC. It covers 138 countries and territories in all regions. Data was collected via expert surveys comprising almost two thousand questions. Local and regional teams of researchers were engaged to ensure optimal data collection and representation. Undoubtedly, local researchers know their environments better than survey companies sitting in their white towers in the Global North. Global quality assessors were also recruited to ensure conceptual and data accuracy and consistency across the various nations. GIRAI thus has a much larger footprint than Stanford’s. The word global works in the former case.

While a unique RAI definition is not yet available, GIRAI offers its own. RAI is conceived as AI that “respects and protects all human rights” and champions the principles of AI ethics. That is undoubtedly a broad definition, unlike Stanford’s seemingly minimalist one. UNESCO’s ethical AI recommendations, perhaps the most widely acknowledged as over 190 countries have officially endorsed them, guide the report’s ethical approach. The “all” preceding human rights is probably the most interesting as, more usually than not, human rights are limited to civil and political rights, with Article 19 of the UN Declaration dictating the agenda — while economic, social and cultural rights frequently fall through the cracks. If AI is to be really “responsible,” then it must consider all human rights regardless. Of course, the devil is in the implementation details, especially when dealing with indices and data that must capture qualitative components.

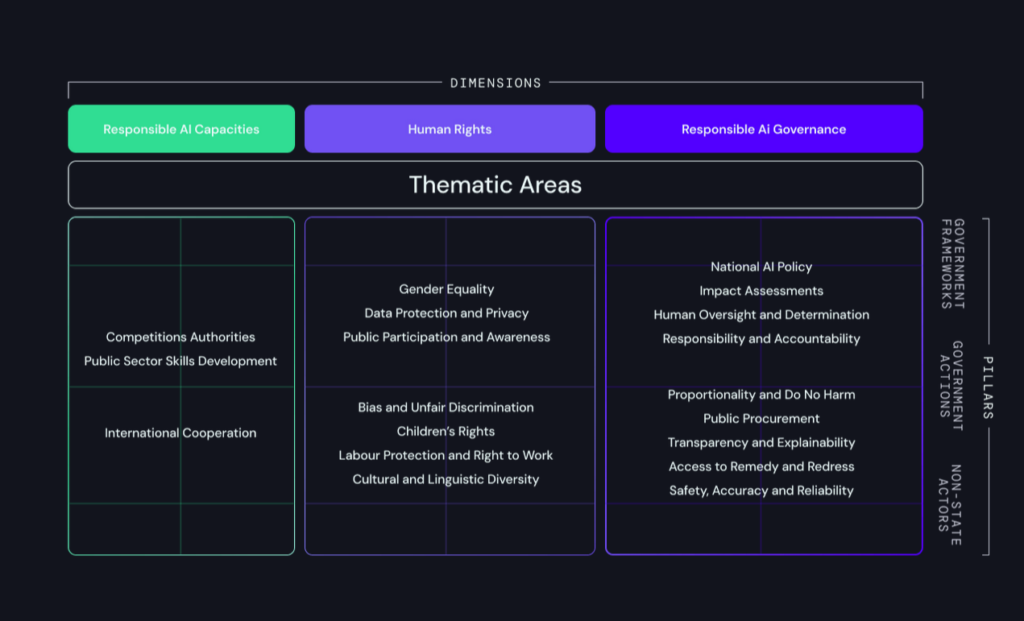

Getting there is a function of the conceptual framework the research develops. GIRAI has undoubtedly created a sophisticated framework comprising 19 areas classified under three distinct yet related dimensions or clusters. These are complemented by three pillars, essentially the agents or actors of the so-called “AI ecosystem” that interact with the 19 areas in various ways and set them in motion. The figure below, directly taken from GIRAI’s report with an unavoidable black background, neatly summarizes the approach.

I assume the three dimensions comprise what GIRAI calls “the AI ecosystem.” Nevertheless, details on how they were identified and developed are not part of the report. On the other hand, the three pillars seem more evident as they cover all societal actors involved in AI — and in many areas, too. In my view, the choice of language could lead to some ambiguity. For example, government actions include the development of government frameworks, etc. I would have instead used government policies and strategies and government-led implementation to sharpen the boundaries and facilitate the identification of indicators for each. Moreover, linking and sequencing the pillars is also possible. For example, from experience, we know that government “actions” without government policy or framework usually lead to failure. Additionally, involving non-state actors in either or both government pillars demands policies and actions from governments to make participation binding and thus meaningful.

The cluster distribution of the 19 thematic areas also seems problematic. The rationale for the above classification has not been shared so far. For example, I could argue that public procurement is a capacity feature many Global South governments lack. Moreover, capacity is a cross-cutting “dimension” needed to set off the other two clusters. Again, linking and sequencing clusters is essential. Another critical issue is the relationship between AI capacities and governance and most nation-states’ existing capacity and governance structures. AI capacity and governance do not exist in a vacuum. Instead, they should build on on-the-ground structures that could be refurbished or disrupted to master the new technologies. The same goes for human rights, which, at the country level, depend on national human rights institutions and machinery that oversee their implementation. The report briefly mentions that governance and human rights data from the World Bank and Freedom House were used to create additional coefficients to refine the estimations. Finally, data on state capacity, degree of digitalization, and digital government development, among other perhaps critical indicators, are missing. However, note that labor and cultural and linguistic protection pop up on the human rights side. Still, the rights to social security, free education, health, and an adequate standard of living, all part of economic and social rights and oft-cited AI targets, are conspicuously absent.

Statistically, asymmetrically allocating thematic areas might end up privileging the cluster containing the most significant number. In GIRAI’s case, the AI governance cluster encompasses almost 50 percent of all thematic areas, while the capacity dimension seems underrepresented with three indicators. As mentioned, capacity is usually a general-purpose driver needed to undertake any action by any agent, especially in the South of the Global South, so one should expect precisely the opposite. While such a distribution does not impact overall GIRAI scores, it can introduce bias in the scores on AI capacity, governance and human rights the report provides. One way to counterbalance this is to introduce weights per cluster, as the index has effectively done for the three pillars (see second part of this post). In any case, sharing a theoretical framework or a change theory could help connect all the framework dots.

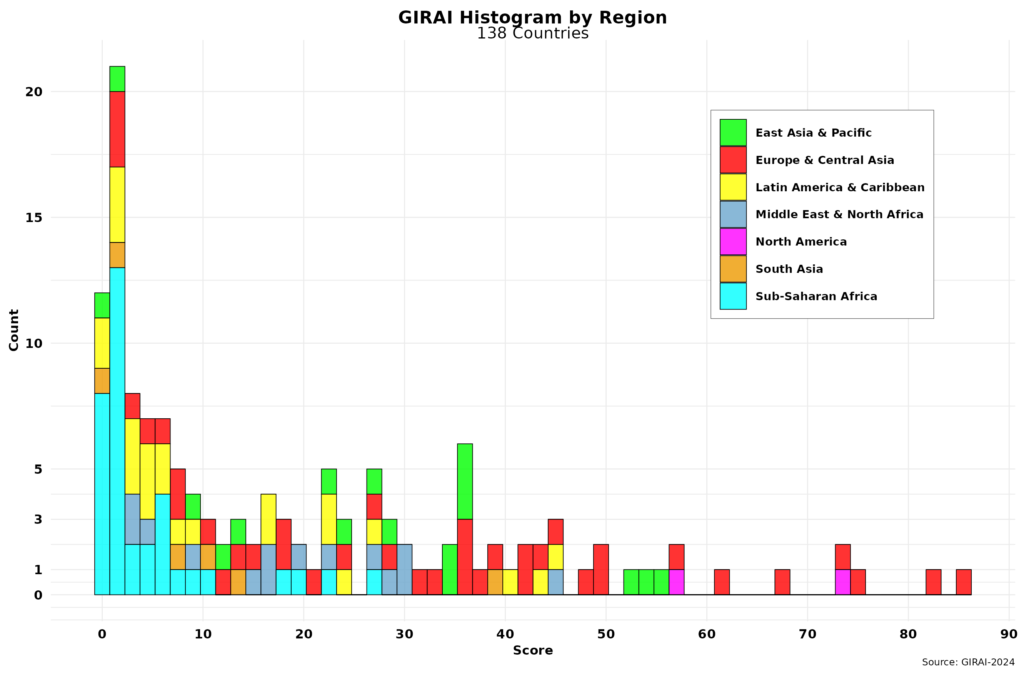

While covering many nations and territories, country selection seems to have been opportunistic, depending on the research contacts and partners the GIRAI team and funders had at the time. As a result, geographical coverage tends to overrepresent a few regions and subregions (sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean) while underrepresenting others (East Asia and Pacific and Central Asia).

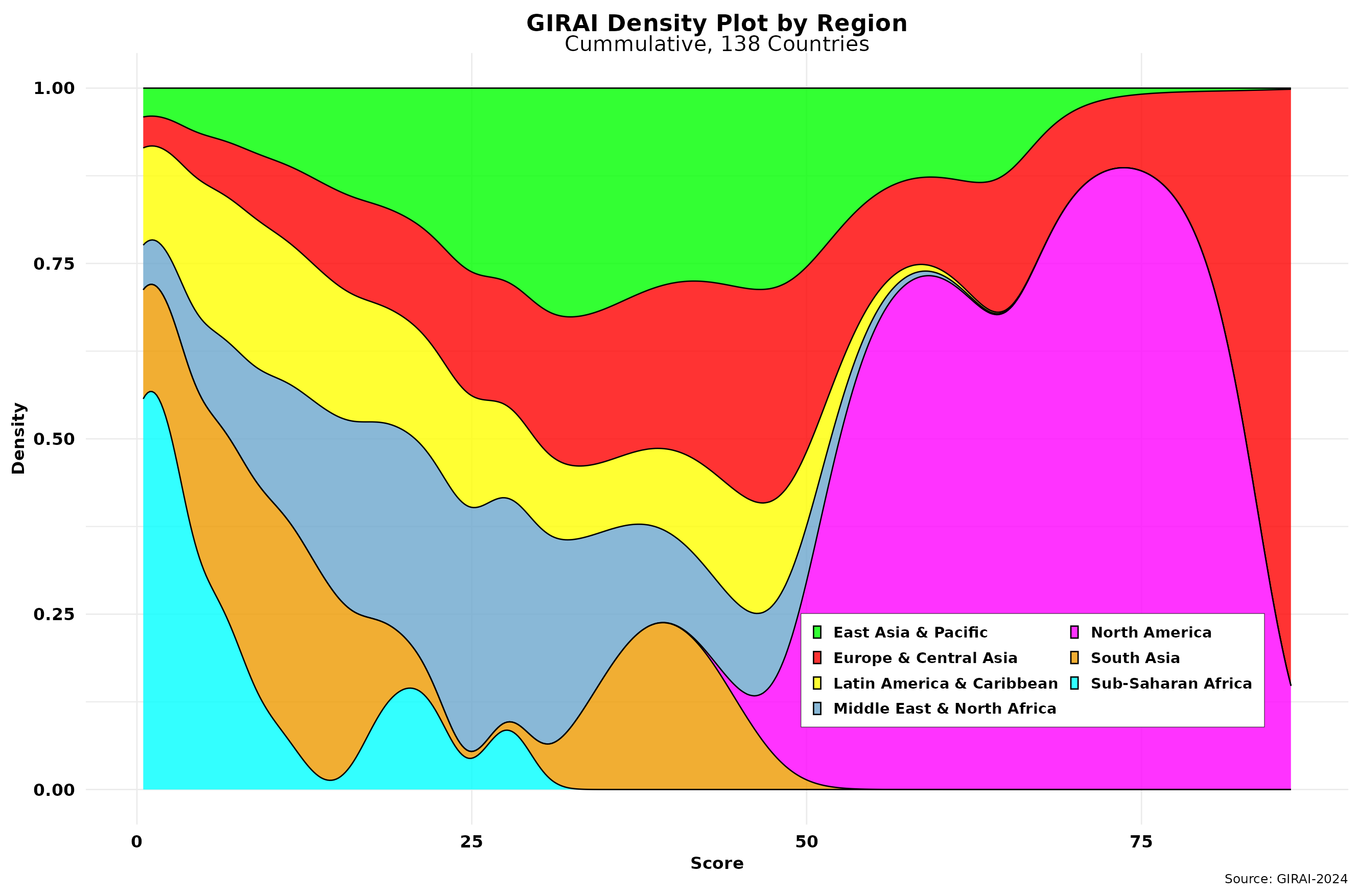

If GIRAI scores were spread out following a normal or Z distribution, that should not have raised any issues. However, most countries score surprisingly low, as shown in the histogram below.

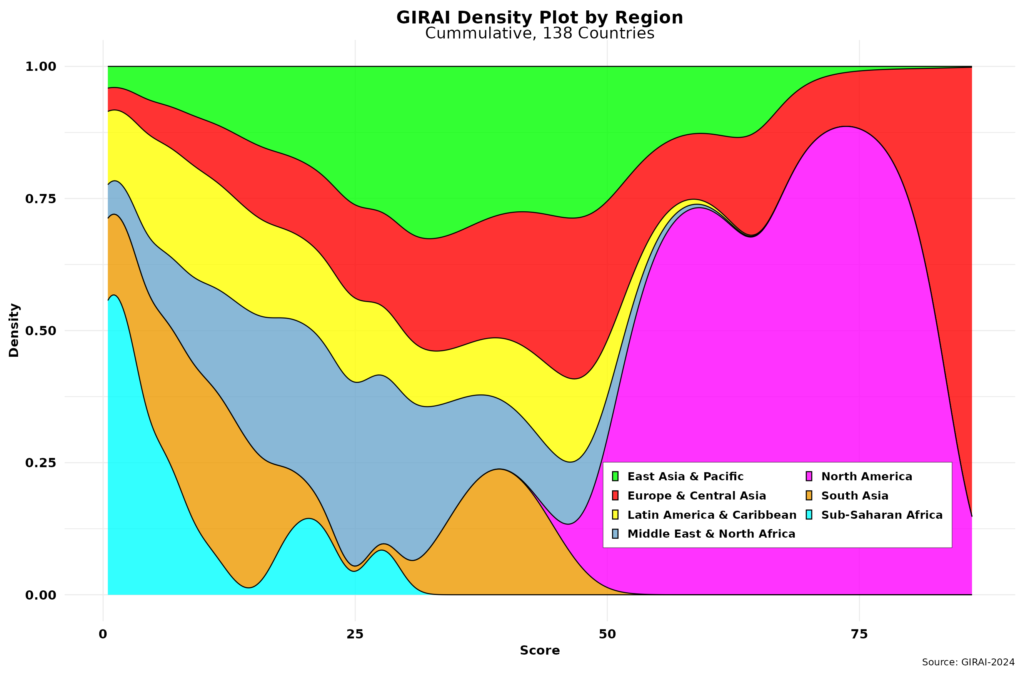

Indeed, 47 percent (65) of countries score below 10. On the other hand, only 12 countries (8.7 %) cross the 50-point barrier. Brazil is the top upper-middle-income country (UMC), ranked 18 overall, while Ukraine and the Philippines have somehow beat China (ranked #2 in the Global Vibrancy Tool). In addition, almost 40 percent of all countries are either low-income or lower-middle-income, where we should expect a relatively slow and paced dissemination of AI, responsible or otherwise. In any case, GIRAI’s score dispersion reflects a power law distribution usually associated with winner-takes-all approaches. The cumulative density plot below depicts the situation in relative terms.

Indeed, 47 percent (65) of countries score below 10. On the other hand, only 12 countries (8.7 %) cross the 50-point barrier. Brazil is the top upper-middle-income country (UMC), ranked 18 overall, while Ukraine and the Philippines have somehow beat China (ranked #2 in the Global Vibrancy Tool). In addition, almost 40 percent of all countries are either low-income or lower-middle-income, where we should expect a relatively slow and paced dissemination of AI, responsible or otherwise. In any case, GIRAI’s score dispersion reflects a power law distribution usually associated with winner-takes-all approaches. The cumulative density plot below depicts the situation in relative terms.

Next, I will examine the index and showcase some data.

Raul