Cyberspace Mansions

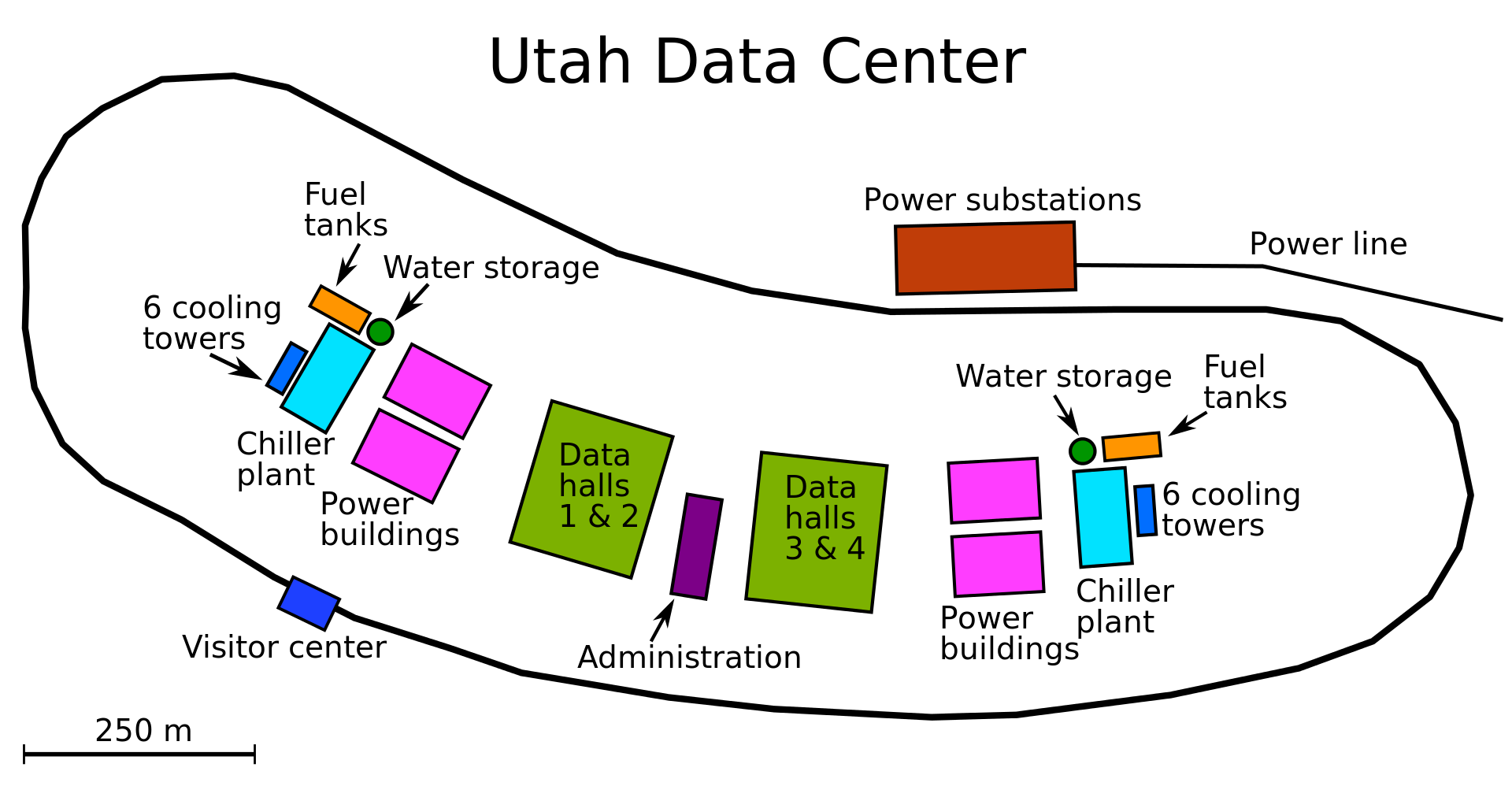

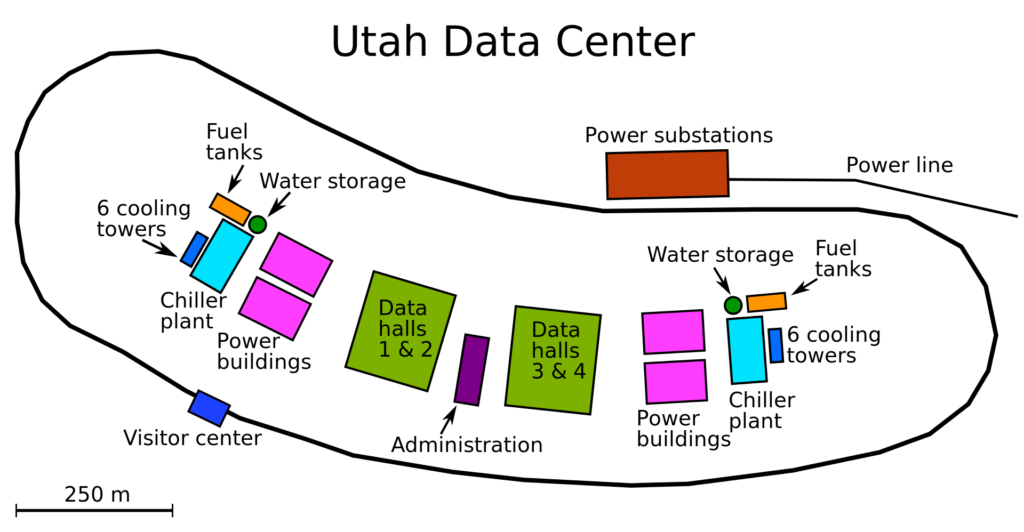

In 2009, amid the Global Financial Crisis, the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) announced plans to create a 1.2 billion dollar data center (DC) in Utah. Indeed, surveillance once again proved it is immune to economic disasters, regardless of magnitude. In any case, actual construction began only in 2011, after government approval. The project was finally completed in 2014 – after the Snowden revelations- having experienced several delays and demanding an additional injection of 300 million dollars.

Full DC details are not readily available for the usual “national security” reasons. Nevertheless, we know the Utah facility occupies almost 100k square kilometers, with 10 percent allocated to data storage alone (racks, servers, routers, hubs, etc.). It requires 65 megawatts of electricity and 1.7 million gallons of water to sustain daily operations, allegedly employing 10,000 people. The facility’s actual data capacity is unknown as officials will not reveal it but are prompt to pinpoint it, which could quickly expand it. However, the NSA has implicitly acknowledged that the Utah DC could store thousands of yottabytes (1 x 10^24) of data. In 2021, 79 zettabytes (1 x 10 ^21) were created globally. So, in theory, the NSA Utah behemoth could store all that – and more.

While the Utah center is certainly not the typical Internet DC, it illustrates the tangible and real requirements such facilities must consume to sustain the digital world. It is also an example of the demands such centers can place on the environment, which are not just limited to energy consumption alone. Of course, storing zettabytes of data also requires producing the hardware and software to store and manage it adequately. Undoubtedly, physical devices provide the oxygen that allows digital data to breathe and live a happy life, short or long; it does not care. DCs are where the so-called Cyberspace resides, in very tangible and real locations churning bits and bytes incessantly, releasing lots of heat and generating plenty of loud noise.

The Hidden Abode of Digital Data Production

Demystifying the alleged “immaterial” nature of digital technologies is not complex if we direct our gaze toward the production processes required to generate the trillions of trillions of trillions of bits that are integral parts of the so-called digital economy. Like oil, data demands significant capital investments that, in principle, could challenge environmental sustainability. The best example and ideal proxy here are the ever-growing numbers of DCs, albeit unevenly distributed around the globe. Needless to say, the recent pandemic accelerated their growth, given the hefty increase in demand.

DCs come in five flavors, Colocation, Enterprise and Hyperscale being the most popular. Recently, the so-called Edge DC has popped up. In this case, smaller DCs are placed closer to end users to reduce latency, a must for applications such as autonomous vehicles. These relatively small beasts are expected to drive DC growth in the short run in partnership with Colocation and Hyperscale deployments. Advanced cloud services are optimally provided by Hyperscale and Edge DCs, with Enterprise playing a minor role.

According to reliable data sources covering 110 countries, over 8,500 DCs were in operation in the first half of 2022. Over 30 percent of them were located in the U.S. alone. Germany, the U.K., China, and Australia, none having more than 6 percent of the global share, were distant followers. Demand for DCs varies by country. For example, the UK’s DCs support financial services, while those in Germany are geared towards industry and manufacturing. On the other hand, China and the U.S. face a more multisectoral demand. Regardless, a centralization process is already at work, at least in the case of Hyperscale DCs, where three companies (Amazon, Google and Microsoft) own 50 percent of them.

DC’s growth in recent years has been driven by an investment shift to emerging markets and regions. Such a change partly stems from energy requirements in a context where sustainability issues take center stage in dominant countries and regions. Note that Edge DCs are an excellent alternative in this case. A 2020 report predicted that by 2025, the sector will have over 2.3 million full-time employees, up from 2 million in 2019. The pandemic will probably provide a solid boost to such numbers. At any rate, compare that to those working in Facebook or Google (both under 120k globally). Again, colocation and Cloud DCs are the main job magnets, the latter being the core engine. DC’s capacities and skills include over 230 job roles, many requiring university or technical degrees – albeit mechanical and electrical engineers are the most sought. On the other hand, women are seriously underrepresented, as expected.

Revenues, investments and rates of return are also on the increase. A 2022 report targeting 55 markets and just under 2,000 DCs shows that Hyperscale cloud providers had revenues amounting to almost 125 billion dollars, 50 percent going to U.S. companies alone. A 2022 survey of DC providers indicates that total investment doubled in one year, reaching a peak of almost 60 billion dollars. At the same time, internal rates of return increased an average of 50 percent over the same period. Again, the pandemic-triggered data tsunami is clearly at work here. DC power capacity is a crucial indicator to attract new investors to the sector. The Washington D.C./Virginia Hyperscale DC market, comprising many centers, is at the top of the list with a capacity of almost 1,700 megawatts. It is expected to accelerate its growth shortly.

So What Else is New?

The above DC overview shockingly resembles the inner workings of traditional industry and manufacturing. Most of the traits and trends associated with the latter are part and parcel of the former. Agreed, DCs are a far cry from the cotton factories typical of the first Industrial Revolutions. Undoubtedly, they are much more sophisticated and in the same league as modern manufacturing enterprises. However, one of the most significant differences emerges when we look at the distribution sphere of DCs. Their final output does not require any traditional means of transportation. We do not hear the noise of trucks and trains loaded with containers full of commodities desperately seeking markets to be sold to anxious customers around the world as soon as possible. Here, what happens in DCs stays in DCs.

In fact, customers are the ones doing the “walking” via high-speed telecom infrastructure that allows them to enter the digital domain, the wonderfully wild world of Cyberspace. DCs are the gateways to the digital realm, and unlike other industries, users do not need to spend any time choosing which DC they need to access. In fact, they might not even know that DCs are doing most of the heavy lifting. Here, the so-called Platforms appear to them as the primary intermediaries, the actual entry points to Cyberspace. But in all cases, the cloud is a factory.

Perhaps more shocking is that pundits and many researchers tend to ignore the “materiality” of DCs. It probably started in the late 1990s when Negroponte published his best-selling book. I do agree with the research that argues he got it all wrong. Being a bit more generous, one could say he got it half right, at best. On the other hand, many academic papers attempting to determine the impact of digital technologies on the environment use the number of Internet or mobile phone users as critical indicators. And from there, they run their sophisticated econometric models to make their point, for or against. If we had to choose one indicator, the most relevant would probably be the number of data users use and generate over time. Indeed, people can be connected to the Internet, but given access costs and broadband limitations, they might use or create small amounts of data stored in one of the eight thousand-plus DCs.

Any assessment of the impact of digital technologies on the environment must factor in the relatively simple production process that converts keystrokes, clicks, images and sound into digital data. Anything else is just analog noise.

Raúl