The last time I visited Eswatini was in late 2019, three months before the COVID-19 pandemic almost brought our collective imagination to a halt. Digital government support was the excuse for the business trip. I had been there a couple of times before and was thus familiar with the territory. Elections held the previous year had reshuffled the government. A new prime minister was now calling the shots and had appointed the eldest daughter of the King as ICT Minister.

Young and dynamic, the Princess Minister generated plenty of expectations, still at their peak when I arrived. Interacting with the key players on the ground was part of the job. A planned meeting with the ICT Minister never materialized, so I had to settle for catching up with the ministry’s Principal Secretary. He informed me she was out of the country, but that did not impede further collaboration with the ministry.

Among the many meetings on the agenda, one yielded a surprise. The CEO of Eswatini’s Royal Science and Technology Park (RSTP), which was formally launched in 2012 (note: the website does not support secure connections), invited me to visit the recently launched National Data Center (NDC). I was completely unaware of its existence, but I gladly accepted the invitation to see the infrastructure firsthand. At the time, the data center, already at the Tier-III level, was offering colocation and basic cloud services to clients. The RSTP location I visited was a state-of-the-art building with nothing to envy in the developed, high-income world. The data center facilities were not as impressive, comparatively speaking, but they provided much-needed services.

My first question was about financial sustainability, as Eswatini is a small and lower-middle-income country (LMIC). In any event, the country was already ahead of many others in this regard. And DCM (datacentermap.com) has a record for NCD. However, NCD is run more like a state-owned enterprise, encapsulated within RSTP, whose core goals are focused on R&D. That is certainly unique in this profitable environment. What about all other data center operators?

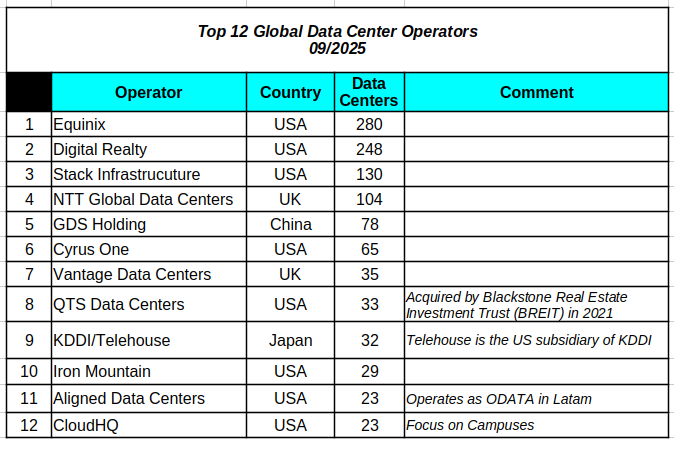

The top ten global data center operators are listed in the table below, compiled from a 2024 report, DCD data, and my research. Note that I am distinguishing between cloud providers and data center operators, as I did in previous related posts. Cloud hyperscalers are thereby not part of these proceedings.

Most of the data center numbers are from DCM. Other information, as well as host country and comments, is from either company websites or the business literature. I have excluded operators with a U.S.-only focus, as the U.S. has the largest data center market in the world. Assessing operator size is a function of the number of sites, the square meters their sites occupy, and the energy capacity they can offer while keeping the humming factories running 24/7. The table uses the number of locations as the primary indicator, as access to the other factors is not always readily available. The implication is that operators running smaller facilities in large quantities in less profitable markets may rise in the rankings.

In any event, what is perhaps more surprising is that no operator has a commanding market share location-wise. Take Equinix, which, with fewer than 300 facilities, does not even reach 3 percent of the total number of data centers globally (10,725, as of the time of this writing). Moreover, the top 12 companies together account for only 10.1 percent of the total. These are hardly indicators of sheer centralization, indeed. Note, however, that except for GDS, all operators are based in advanced capitalist countries, with eight of them rooted in the U.S.

So, it looks like these outfits are primarily interested in the most profitable markets in the developed world, with the U.S. being the most attractive place for investors, given its current data center market share (almost 40 percent of the total). They can then take on the most profitable ones in the developing world, as competition among them intensifies. But that also opens the door for smaller operators that can supply services in markets the big guys deem unattractive for now. That can partly explain the relatively large number of operators worldwide, well over 250 by some accounts. Centralization does not mean competition ceases to work. Not at all. Here we have a case of segmented competition. Those at the top are looking for superprofits, not just average profits, and thus focus on the largest markets to maximize revenues. However, average profits are sufficient to attract new investors and operators to smaller, less profitable markets. In that context, my early prediction is that concentration and centralization will accelerate in the short run as the data center market continues to grow at the speed of light. The much-anticipated AI tsunami will undoubtedly be a critical driver in this process—assuming the AI bubble will not suddenly burst any time soon. And hyperscalers will probably start acquiring data center outfits in lucrative markets to expand capacity, in addition to launching new sites.

In any event, who are the leading data center operators in the developing world? The business literature often offers valuable insights, including top-ten lists for various regions, including Africa, Latin America, and Asia and the Pacific, among others. For example, while the Africa list conveys helpful information, we then read that the top-ranked operator is actually majority-owned by Digital Realty. Moreover, many of the top 10 operators in Latin America are actually U.S. companies. And the Asia Pacific mapping is missing India-based operators.

I do not have access to the DCM data that provides detailed information on data center operators. My pockets are not that deep and already have a few irreparable holes. One way to answer the question is to use a proxy calculation.

In the previous post, I highlighted the top 20 data center cities in the developing world, excluding China. According to UNCTAD’s country classifications, the DCM data set comprises 55 developed economies and 114 developing countries; Kosovo is excluded because it is not classified. Accordingly, developing economies sans China host 2,043 data centers, roughly 19 percent of the total sample. Adding China increases that percentage by just over 3 points, which does not make a substantial difference in the end. In any case, 81 percent of data centers comfortably reside in the developed world—or 78 percent, if we exclude China.

Regardless, the top 20 data center cities in the developing world account for 31 percent (630) of all sites in that economic category. We also know that in many of them, data center diffusion is sharply uneven. Indeed, usually one city, ordinarily the country’s capital, is the strongest magnet, while the rest struggle to get off the ground. In this light, we can use such cities as proxies to identify the leading data center operators in the developing world.

According to the data (DCD sourced), there are over 216 operators in the top 20 developing country cities, excluding China. That implies that the average number of locations per operator is almost three. However, that is slightly misleading, as more than half of them (130) only run one instance. Indeed, the median of the data sample is 1. In fact, only 25 operators run more than five data centers. This corroborates my initial hypothesis that small operators can enter the market as long as they target its lower segments, where securing superprofits is more challenging. And yet, they can still make a buck.

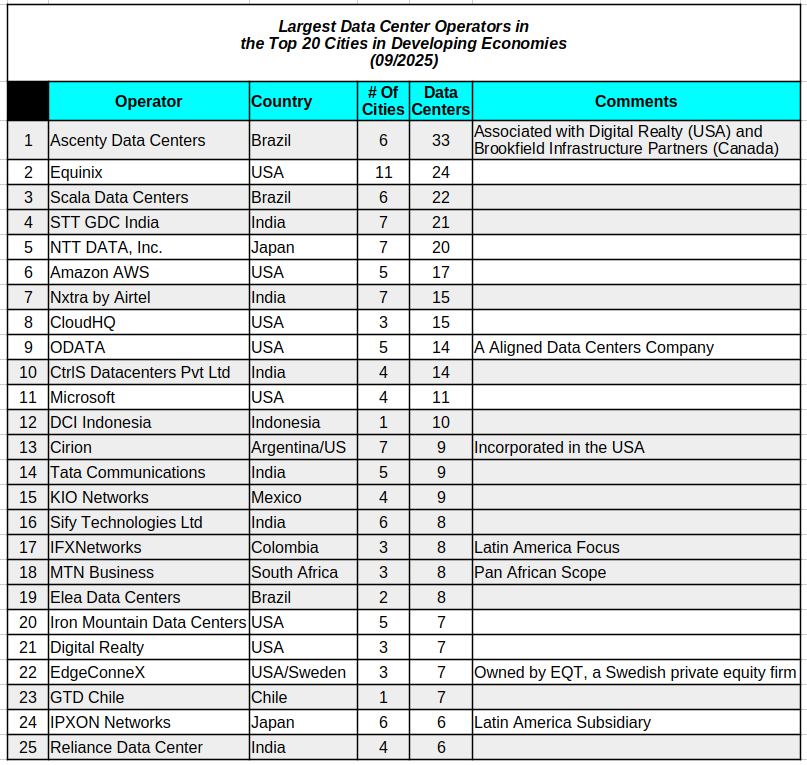

The table below lists the top 25 data center operators. It includes the company’s home country, the number of cities it operates in, and the total number of data centers it runs in the top 20 developing economy cities. Operators from those countries are highlighted in gray.

U.S. companies lead in the number of operators, with eight, followed by India with six. Brazil is next with three, while Japan captures two spots. We subsequently have 10 countries, each represented by one. Five operators are based in Latin America, while Africa only has one, MTN Business—not Africa Data Centres, as assumed by top-10 listings. Indonesia is the only additional developing country representing Asia and the Pacific. Fifteen of the 25 operators are based in the Global South. These companies are most likely the top 15 within the developing world.

Regarding city coverage, only 13 have a presence in 5 or more cities. Equinix leads in this rubric. It is the only operator to cover more than half of the cities in the data sample, serving Latin America, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and South Africa. In contrast, all five Latin American operators are regionally bound, except for GTD Chile, which only operates locally. The same goes for the top Indian companies; Nxtra, STT GDC, Sify, and Tata are entirely focused on India—albeit Nxtra recently opened a data center in Lagos. Such a difference uncovers another crucial difference across operators in developed and developing country data center firms: capital mobility across regions. Many reasons could explain this, ranging from international capital investment costs to local competition in potential destination sites. More research is needed in this regard.

In sum, intense competition still prevails in the data center operator space. Such a space is still relatively new and has developed unevenly around the globe. One country is the leader by far in both data center geography and data center operators. Other developed nations follow from a distance. As expected, most developing nations lag far behind. And yet, we can identify a very dynamic data center geography and relevant operators within the latter group of countries. They thus have an opportunity to grab the bull by its horns. But for that to happen, they need to act in sync with other actors and sectors. The accelerated development of AI should be a catalyst here and not an excuse to sit on the fence, sipping wine endlessly.

Raul