Policy Evolution

Comparatively speaking, AI national policies and strategies have evolved much slower than other digital strategies such as ICT, Digital Government, and Open Data. That might seem paradoxical given the systemic benefits and risks of the revived and now resurgent technology, undoubtedly more significant than any previous innovations. Nevertheless, in the early days, skepticism and even open opposition to policies and regulations (two very different animals indeed!) prevailed, based on the well-known argument that innovation should not be controlled in any way or form.

The tide changed once AI’s dark side became tangible, already harming the lives of thousands, if not millions. The debate then switched to identifying the policies that could be set to navigate the gamut of risks. Unfortunately, that did not stop the big push by Big Tech to promote “ethical and responsible AI” as a last-ditch attempt to enshrine self-regulation as the only way forward, thus avoiding any sort of public policy development. Making policy a synonym for regulation did not help. However, public policies do not set regulations. Instead, they establish an overall strategic direction. On the other hand, regulations set the behavior of actors and agents. So, self-regulation can still slip through policy interstices.

The best example is the OECD principles and recommendations for trustworthy AI, already endorsed by over 50 countries and the G-20. Its five principles touch on at least three of the four AI policy areas depicted in our framework. The principles mainly focus on the fair use and implementation of AI systems, thus having a significant ethical component. Moreover, they call for governance mechanisms that involve all stakeholders but assume self-regulation as the ideal model to reach the final outcomes.

The development of AI public policies first started in 2014, when a selected number of countries endorsed ad hoc policies to handle the advent of autonomous vehicles while welcoming the arrival of the newly coined Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). While limited in scope, such policies and specific regulations of actors involved in that space open the door for broader thinking within the confines of the nation-state. More so if the potential negative impact of the 4IR on national economies was factored in a global context where two giants, the US and China, were well ahead of all others, even without having national AI policies.

Policy Development Status

Determining which countries have already approved a national policy is not straightforward. The best resource here is the OECD AI Policy Observatory, which includes 62 countries plus the European Union (last checked on 20 October 2021). However, the data is not just limited to AI policy development. Expect to find additional information on Digital Transformation and Data strategies too. Moreover, the data does not provide a clear marker for countries that have already approved national policies and differentiate them from those still in the policy design phase. Finally, downloading the data for analysis is not simple as the data set is not part of the well-known OECD data sources accessible via its own APIs. And the observatory does not offer the option to download all country data in one shot. Not all countries are covered, so additional research was needed to ensure full global coverage.

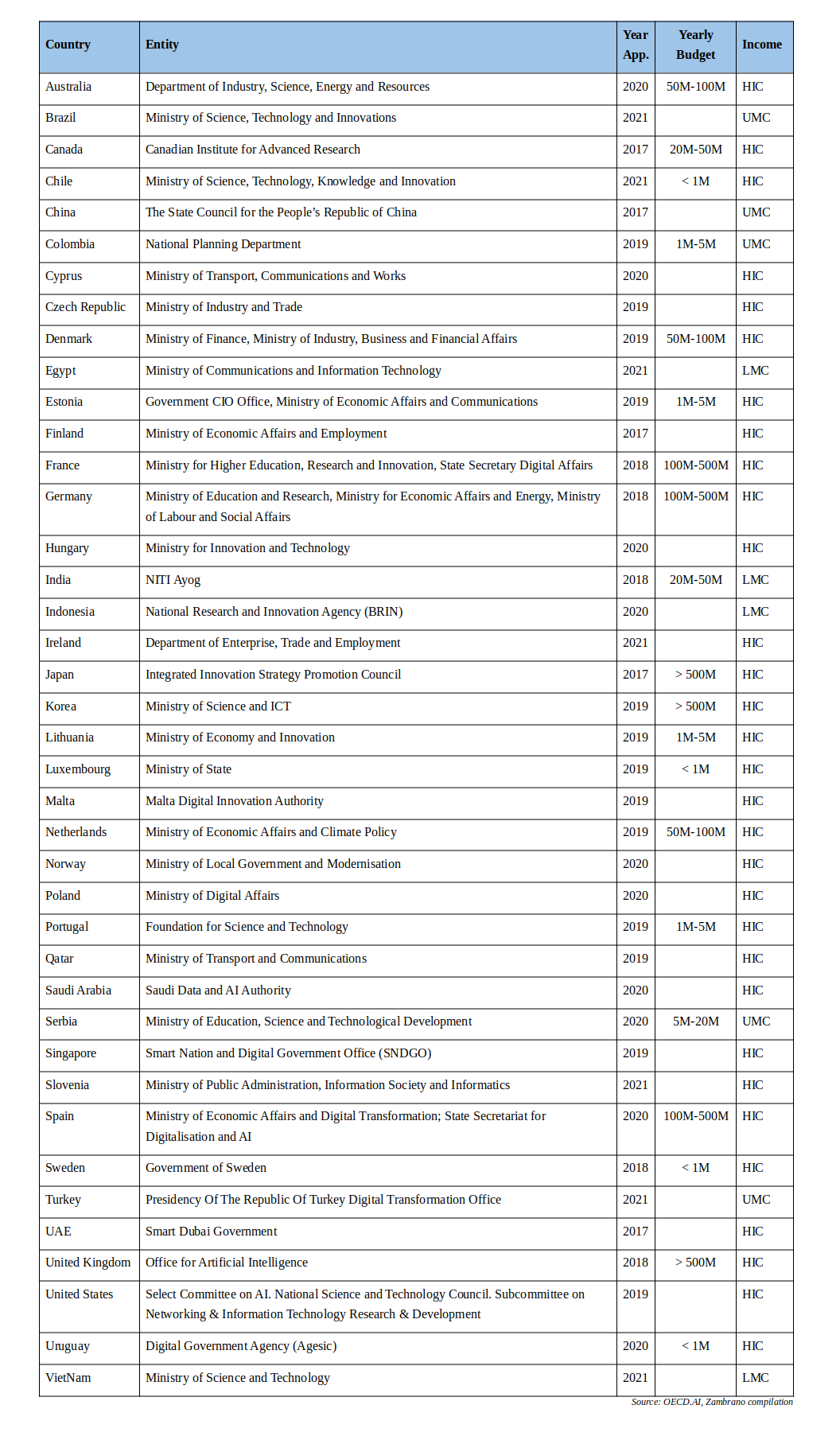

As of the end of last month, 40 countries had approved AI national strategies, while at least 23 were in process. Canada was the first country to complete its national strategy in 2017. Egypt, Turkey, and Vietnam are the latest additions. The table below lists the countries in alphabetic order and offers an overall summary.

As expected, most countries with approved AI national strategies belong to the high-income category, as defined by the World Bank. The other nine are either upper-middle or lower-middle-income. On the other hand, low-income countries are conspicuously absent, while no country from Sub-Saharan Africa made the cut. Two of the four lower-middle-income countries, Egypt and Indonesia (downgraded by the WB, thanks to COVID-19), recently joined the exclusive club. Most probably, more will be doing the same in the medium term.

Moreover, 50 percent of all countries are in Continental Europe, and 29 are part of the so-called industrialized nations. Recall that countries can be classified as high-income and still be considered “emerging.” A high correlation between country income levels and AI policy development is at work here. That should not surprise us, as this pattern is found in other policy processes, digital or not.

Policy Typology

Using the framework shared in the previous post to study the various AI national policy documents provides the tools to develop a typology of AI policies. Not all policy documents are available in English (Indonesia, for example), so the analysis is limited. The critical link is between AI readiness and the localization and contextualization of the four policy dimensions. In this light, three cohorts of countries are identified.

- Behemoths. The U.S. and China are the only members of this cohort. They have comprehensive AI policies backed by large public and private resources. They also have geopolitical ambitions and compete for global supremacy, with national and digital sovereignty as flag bearers. While the US is still far ahead, China seems to be catching up. As with any other sector, competition benefits all of us – as long as military conflict does not get in the way. In any case, the AI field is far from being a level one. These two nations are far ahead, and catching up with the rest might be a pipedream in the best-case scenario. Developing partnerships and alliances seems more feasible here.

- Scramblers. Here we find most high-income countries and all 29 industrialized ones. While most policies touch on “ethical and responsible AI” deployment, all seem geared towards preserving and hopefully increasing competitive advantages that support internal social structures and living standards. They also want to develop local AI sectors that propel the former, thus seeking a relative degree of digital sovereignty to sustain the existing state of affairs. However, not all have the same ambition. The Stirrers subgroup comprises countries that want to remain close to the Behemoths while being realistic about their chances of catching up. Included here are France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the UK, all of which have allocated necessary public resources to support AI development, as shown in the above table. The Loungers comprise all other nations going through the policy motions closely following OECD guidelines and crossing their fingers to prevent others from eventually eating their lunch.

- Climbers. Included here are most emerging and developing nations, aware of the magnitude of the challenges they face in this arena but need to take action now to seize short-term opportunities. The AI readiness level is far below the two other cohorts, while gaps in the policy dimension are vast. India is a good example here, suggesting that helping other developing countries is also an opportunity. On the other hand, Dubai, representing the UAE, is mainly focused on the public sector, as is Uruguay, but also has global goals to attract external talent and become an AI global hub in 2030. That is the same model used in the Emirate to become a financial hub. All in all, countries in this cohort show less interest in digital sovereignty, as they see themselves more as filling gaps others have yet to address. They are thus climbing a very steep hill. Nevertheless, reaching the summit might have significant rewards if they find the right path.

AI national policy development is yet another critical symptom of the immense disruptive potential the resurgent technology might have in the medium term. Countries that have so far ignored such policies and strategies need to wake up soon before the last slice flies off the table.

Cheers, Raúl

These three posts are based on a paper I wrote with a colleague on AI Policies in Latin America, which the ACM will soon publish.