While competing theories on public services exist, two of the most relevant deserve special mention. In one corner is the French conception, which stems from the French Revolution and directly links public services to the state within a rights-based framework. It is thus very close to the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. On the other hand, the Anglo-American definition sees public service provision as exceptional only when pervasive market failures must be addressed, since the market alone can close service gaps. In the latter, public services tend to be conflated with “services in the public interest,” which include plenty of private services .

Agreement, however, exists on the fact that public sector interventions in society must generate public value . While consensus on an academic definition of public value is still in the works , the core idea is that public sector activities and investments should not be reduced to economic impact only. Instead, they should also target all core functions and thus factor in social, political, cultural and environmental outputs and outcomes, all of which should benefit the population in general.

Recent developments in public value theory have identified three interrelated areas that should be part of analyzing the public sector’s impact on society . These are: 1. Legitimacy. 2. Capacity (creation and deployment). And 3. Public value (creation and evaluation).

Legitimacy is closely related to the previous discussion of governance instances and mechanisms within the sector and embedded in specific power configurations and distribution. In theory, involving stakeholders and beneficiaries in public sector decisions to invest in public service provision can strengthen legitimacy.

Public value creation is usually associated with public service provision, one of its main outputs. However, its evaluation should instead focus on outcomes related to core public sector functions that enhance overall human development in the medium and long term. For example, an excellent digital platform delivering health services is necessary, but much more is needed to reach desired outcomes, such as increasing overall life expectancy. More often than not, the latter results from multiple public services and complementary policy interventions.

The capacity component of public value provides a springboard for introducing state capacity into the analysis. The vast academic literature on the topic has yet to generate agreement on a single definition (see, for example, ). The fact that state capacity is multidimensional is undoubtedly one of the barriers .

Given this note’s primary objectives, which look at the impact of AI in the public sector, introducing a simplified version of state capacity can go a long way . In that light, state capacity comprises three elements.

- Institutional capacity. The capacity to design and implement policies, provide public services, and the legal capacity to sustain the rule of law. A professional and qualified civil service operating within public institutions with clear “rules of the game” is part of the equation.

- Fiscal capacity: The capacity to sustainably capture financial resources via taxation and other sources, including external ones.

- Infrastructural capacity. The capacity to carry out institutional and fiscal responsibilities in all the territories under state control.

Global South countries must have the institutional capacity to harness complex technologies such as AI. That includes adequate technical knowledge and managerial and administrative capacities to run complex initiatives effectively and transparently. They must also access sufficient fiscal resources to finance AI investments and manage financial disbursements efficiently, including the usually mandatory competitive procurement processes. These processes, in turn, require the creation of complex documents, such as requests for proposals (RFPs), which require elaborate technical specifications. Finally, they should be able to implement service delivery nationwide, especially in rural and marginalized areas.

One crucial research warning is to avoid confounding state capacity and political regimes. It is frequently assumed that countries with minimal democratic credentials have high state capacity. However, as Tilly has pointed out , most advanced democracies in the world today have high-capacity states, a status most developing nations still lack . High state capacity is a feature of democratic regimes, not a bug. That is why low-capacity, non-democratic regimes resort to force to ensure social control and legitimacy, including frequent Internet shutdowns.

State capacity is largely absent from research and discussions on the deployment of AI and ICTs in the public sector. The implicit assumption is that state capacity varies little across nations, complemented by the idea that so-called “strong” states are invariably “authoritarian.”

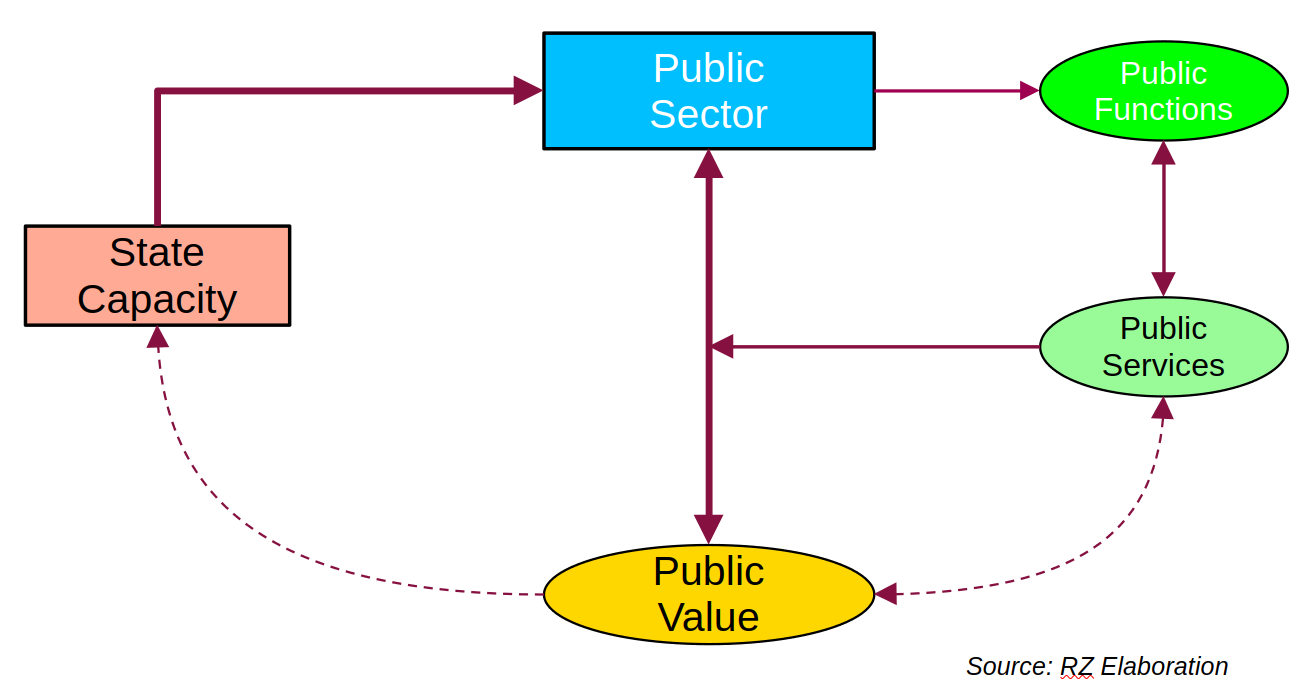

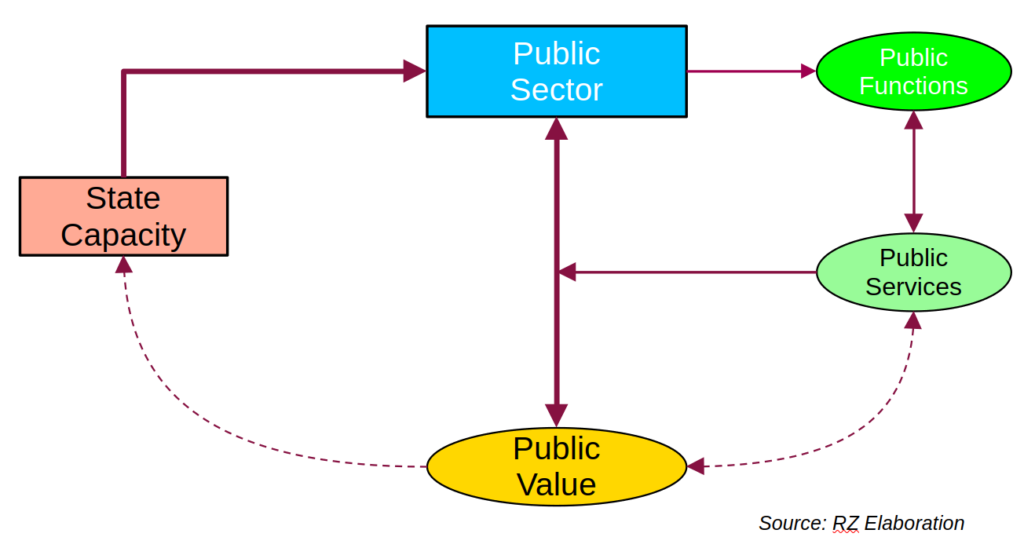

Undoubtedly, the scope of the public sector is complex, as a series of previously described interrelated factors must act in concert to effectively generate public value, which is its critical goal. The figure below depicts the interaction among such factors.

The key here is the feedback mechanism between public value and state capacity, as well as public value evaluation and public services. As noted above, most of the literature on digital technologies in the public sector ignores state capacity tout court, apparently assuming it is irrelevant. Furthermore, the evaluation and assessment of public service provision is usually limited to tangible outputs, such as the effectiveness of a given technology in delivering services. In that light, outcomes immediately fall off the radar screen. In any event, AI is subject to the same structural context, regardless of its level of “intelligence.” Nevertheless, the crucial research question is how much AI can help change these structures for the better—or worse.

The public sector should be further distilled to add more nuance regarding state capacity. Three interconnected layers can be highlighted.

- The macro layer encompasses the “whole of government,” where most, if not all, public sector institutions are expected to cooperate and act in sync to increase responsiveness and effectiveness. Policies, strategies, and regulations play a key role within this layer.

- The meso layer includes individual institutions with discretionary power to make public investment decisions, regardless of existing or planned government policies and strategies. Such entities usually devise subsector-specific digital strategies and allocate public resources accordingly. Importantly, this layer captures the uneven institutional capacities among public entities, with a select few leading the pack.

- The micro level comprises the units, divisions, or groups within a single entity that lead strategy design and implementation while maintaining overall oversight. In some cases, such units act independently, without the direct involvement of high-level officials or division directors.

In an ideal scenario, these three layers should be interconnected with the macro setting of the overall vision and strategy to determine public investments in digital technologies. From a technological disruption perspective, these layers provide entry points for those pushing state-of-the-art technologies, yet they miss their interconnection. The same goes for all those innovators in the public sector who need help understanding its layered architecture.

In the next post, I will examine AI, its deployment and its potential impact on the public sector more closely.

Raul

References