As suggested in the first part of this post, not all platforms are digital. In fact, analog platforms are the older siblings. Its digital counterparts are undoubtedly distinct, their calling card usually being their multisided nature—operating in more than one two-sided market. However, analog multisided platforms have also existed for a long time . And, of course, digital two-sided platforms are out there as well. The best examples are Uber, Netflix and Airbnb, which operate exclusively within traditional economic sectors, competing with analog incumbents and other digital outfits. In that light, the digital domain is a critical differentiator.

Moving from the analog world into this new, virgin territory demands developing tools and technologies that enable humans to enter it. Not surprisingly, access was the first challenge. Closing the “digital divide” soon became the clarion call. But once we are in, we need additional tools to poke around virtually and do what we frequently do (and more) in the now-seemingly-obsolete analog world. Here, the diffusion of the World Wide Web proved decisive. Once a critical mass of digital inhabitants was reached, with hundreds of millions on board, investments in the digital domain took off, leading to the emergence of digital platforms and the seemingly inevitable enclosure of the digital domain.

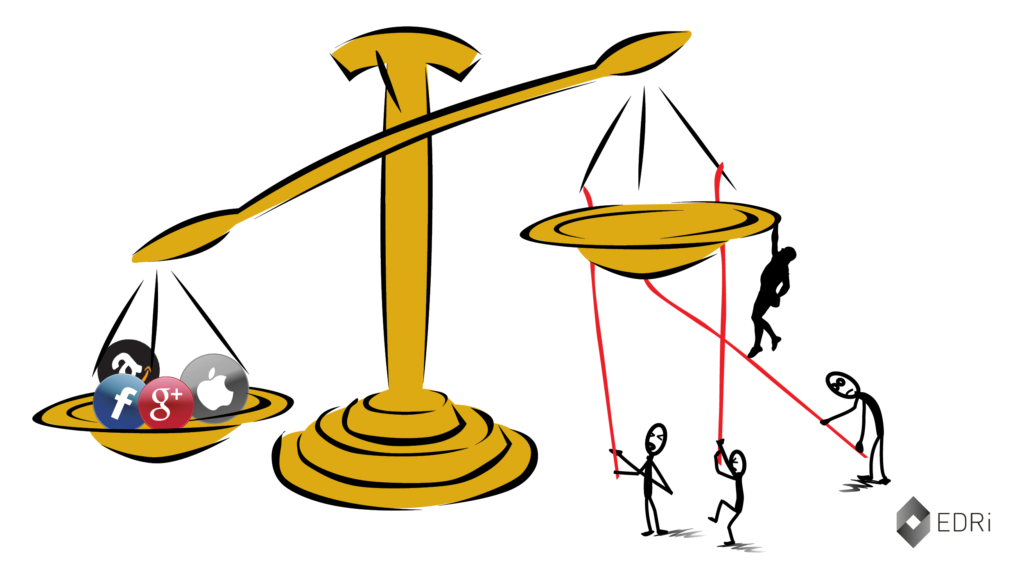

These platforms are sophisticated beasts, constantly developing and deploying the latest digital tools while promoting incessant innovation, whereas analog platforms do not necessarily need to do so in the short term. They are slow pokes, indeed. The new beasts also own and control large slices of digital real estate. While they can compete intensively with analog counterparts, they tend to centralize intermediation across many markets while simultaneously allowing new digital intermediaries to operate within the confines of their exclusive, almost infinitely extensive digital haciendas. What is really new, then, is not the business models per se, but the fact that they operate within a unique domain.

Facebook/Meta is a great example here. Its “new” business model is the good-old advertising model, which accounts for 98% of its billionaire revenue. Granted, Meta has a very sophisticated advertisement model that piggybacks on a global audience of roughly 3 billion people. The scale and sophistication of that advertisement model are unparalleled, thanks to digital technologies. Cannot beat that yet, for sure. Contrast such an “innovative” business model with that of Uber or Airbnb, which undoubtedly look like the analog two-sided markets they are trying to disintermediate at all costs. I will submit that they also lack “new” business models. But they are playing the game in a very different field, which they happen to own or control.

Indeed, not all digital platforms are the same. It is a new subspecies comprising different breeds. However, just like in the case of platform definitions, consensus on the number of breeds is yet to happen . It all depends on the microscope we use to examine the various specimens. Certainly, one could take different paths here. That is precisely what has happened so far. I believe an approach that centers on the overall production process digital platforms embrace and sustain should do the job.

Any production process comprises four phases: 1. Production itself. 2. Distribution. 3. Exchange. And 4. Consumption. And let us not forget that these are tightly interconnected and can overlap. For example, productive consumption should not be confused with consumptive production. The former simply consumes raw materials and inputs effectively during the production phase. The latter occurs when a consumer contributes to the other production spheres. On some platforms, this continually happens, as users’ actions and even personal details are captured semi-automatically and then immediately fed into the production environment. Moreover, all users/consumers who share information and click on like or similar buttons are integral to the distribution process. Distribution requires adequate infrastructure and equipment to ensure the product or service circulates widely and reaches consumers everywhere. Exchange occurs in the market, where both platforms and consumers can purchase the products and services they seek to satisfy their consumption needs, including productive consumption.

With this in mind, we can ask three basic questions to differentiate and classify platforms. First, what exactly are they producing? Second, what are they actually selling? And third, what is the degree of digitalization of the overall production value chain? So, let us look back at Facebook/Meta. It all starts with algorithms and patents, which give the company an immediate competitive advantage while creating insurmountable entry barriers that deter the competition. Since its creation in 2004, Facebook has amassed over 9,000 patents. Production is thus totally geared toward putting its core algorithms into action. In this light, the company produces a range of digital tools that help consumers use the platform optimally, aiming to improve the effectiveness of the algorithms, old and new, working closely together. However, Facebook does not sell what it produces. Upon registration, users are more than welcome to use its tools for free. Instead, the company sells attention spans, just like any other media outfit, to companies continually looking for more customers and, thus, are more than glad to have a global audience at their disposal. The apparent gap between production and exchange is because the overall production value chain is highly digitalized. Unlike newspapers and similar examples, Facebook does not sell tangible products to end users or advertisers. Distribution and consumption are 100% digital and do not require intervention from the exchange sphere.

Contrast that with Amazon—the store—or its world-leading cloud services. In the latter case, the company clearly sells what it produces, even though most of it comprises intangibles. There is no gap here since the overall production value chain can only be digitized to a point. Infrastructure and hardware of all sorts are indispensable requirements the cloud behemoth needs to deliver a plethora of digital services. There is no escape from that, just like regular brick-and-mortar operations. Nevertheless, there is no real counterpart of cloud services in the analog world. Note that Facebook probably has similar infrastructure and hardware requirements. But the difference is that their production is a means to an end: to maximize eyeballs and increase ad sales.

Limiting the analysis to the top digital platforms, we can suggest an initial classification scheme that will surely need further refinement. While certainly different from Meta, Google falls into the same category. It has a tightly digitalized value chain and does not sell what it produces—web searches being the core product. Apple is much closer to Amazon as it also has its own cloud services and sells its own hardware products to consumers. Microsoft is between the two groups, albeit closer to Amazon and Apple. It primarily sells software licenses, which is what it produces. But it does not sell tangible products, so its value chains are more digitized than the former two, but certainly less than Meta and Google’s. Companies such as Uber, Netflix, and Airbnb play in a different league—the second division—where two-sided market platform teams are enrolled without much hope of being promoted to the premier league. In any event, they all sell what they produce and have their value chains comparatively minimally digitalized.

As multi-sided platforms, Big Tech companies are active in multiple two-sided markets and even compete in them. Cloud computing and mobile phones are the best examples here. In that light, the overall production framework described above should not be applied directly to companies but to the markets in which they operate, without ever losing sight of what is most profitable for them. The same advice applies to policymakers preparing to unleash the regulatory lash.

So how does all this happen in practice? In the next post, I will take a peek at the EU’s Digital Services Act to explore that.

Raúl

References