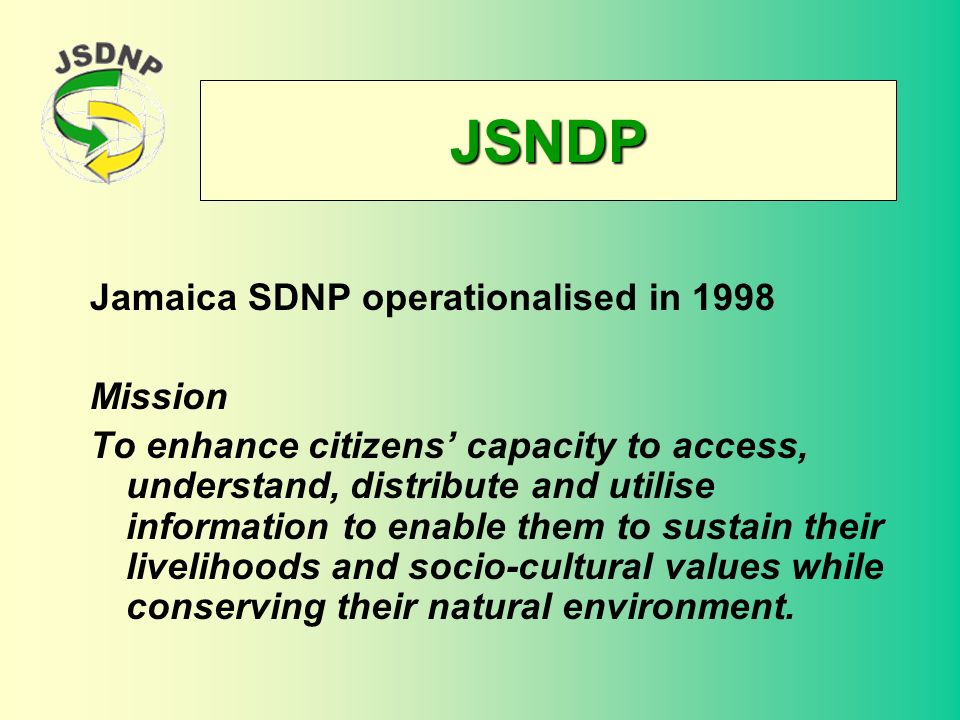

The last time I visited Jamaica was in the early 2000s. A few years before, we had launched the national node of the old and now defunct Sustainable Development Networking Programme (SDNP).  It was labeled JSDNP and did quite a bit of work locally fostering digital technologies and creating and disseminating local content. Unfortunately, JSDNP ended operations sort of unexpectedly in 2006. Now I am playing catch-up with the island’s digital evolution. And thanks to COIVD-19, I was not able to travel. Virtual will never beat the good old analog thing, that is for sure.

It was labeled JSDNP and did quite a bit of work locally fostering digital technologies and creating and disseminating local content. Unfortunately, JSDNP ended operations sort of unexpectedly in 2006. Now I am playing catch-up with the island’s digital evolution. And thanks to COIVD-19, I was not able to travel. Virtual will never beat the good old analog thing, that is for sure.

The pandemic unexpectedly struck the world amid yet another wave of digital technology innovation, thus adding seemingly insurmountable obstacles to an already crowded set of development challenges. Jamaica has not been spared by either. By mid-October, the Government reported over 7,200 cases and just under 150 deaths, women comprising 55 percent of all infections. The virus has gained traction since mid-August, infections growing almost 700 percent since.

Jamaica’s Government embraced ICTs at the beginning of the century. Indeed, digital technologies have been part of Vision 2030, the overarching national development plan, since its inception. A comprehensive ICT plan was first crafted in 2009, and the first national ICT policy approved in 2011, Digital Government being one of the priorities. In 2016, the Government completed a blueprint for deploying ICT in the public sector but fell short of designing a comprehensive eGovernment national strategy.

Despite important gains, ICTs have yet to take off fully. Over 45 percent of the country’s population still lacks access to the Internet. And only 10 percent of those connected have much-needed broadband access, which in turn is relatively costly. The development of Digital Government is also lagging. The latest incarnation of the UN e-Government Development Index (EGDI), covering 193 member states, finds Jamaica in slot 112. Within the region, the island is in slot 24 out of 33 nations.  Back in 2010, the EGDI’s country ranking was higher in both geographical contexts, 89 and 19, respectively. Not that Digitial Government is moving backward. Other countries are, in fact, growing at a much faster pace, thus leaping ahead of Jamaica.

Back in 2010, the EGDI’s country ranking was higher in both geographical contexts, 89 and 19, respectively. Not that Digitial Government is moving backward. Other countries are, in fact, growing at a much faster pace, thus leaping ahead of Jamaica.

The pandemic has shown the critical role governments must play to ensure countries are fully prepared to respond to crises and shield human development gains. Strategically deploying digital technologies within governments to foster responsiveness and effectiveness is not an option but a sheer necessity. Providing essential public services and information via digital technologies is paramount if direct human contact is minimized. It requires a cohesive and synchronized approach to achieve such a goal sustainably.

Jamaica’s Digital Government policies have been historically subsumed under the over compassing umbrella of ICTs with the implicit expectation that the latter’s coattails will hopefully trigger a virtuous cycle in the former. A new national ICT policy is currently under development in the country, and the same perspective has once again conquered the policy territory. Current evidence stemming from both the UN EGDI and leading Digital Government countries such as Denmark and South Korea and Chile and Uruguay in the region pinpoints that public sector digital transformation demands policy-makers undivided attention more so when crises hit. In fact, national Digital Government strategies are the perfect complement to national ICT Policy development, particularly if governments are called to facilitate the latter tout court. Middle-of-the-road approaches will not cut it.

A Digital Government strategy is also the ideal vehicle to reduce institutional fragmentation, augment human and institutional capacities, by-pass technology-driven approaches and minimize ad hoc digital technology public investments, all very relevant to the Jamaican context. The provision of digital public services and information demands the concerted action of key public institutions. The same goes for the creation of one-stop shops that provide such services from a single source. Centralizing common and shared services (infrastructure, applications, security, and so on) across all public entities while decentralizing the public sector’s sectoral digital transformation is at the core of the process.

Hopefully, policymakers will soon turn their full attention to the public sector to embrace digital technologies strategically. The pandemic provides the perfect opportunity for taking this step.

Cheers, Raúl