Having been trashed for the last forty years or so, Governments have unexpectedly taken back center stage thanks to the Covid19 pandemic. The virus does not need a passport to travel around the world, nor any tough immigration legislation has managed to prevent it from freely crossing national borders. No country will be spared seems to be its harsh mandate, in a world where technology and globalization permeate most human interactions. Highly contagious, the only way known today to decelerate its spread is by minimizing direct human contact. In the absence of a global governance mechanism, only national governments can take effective action.

When China first opted to completely shut down Wuhan earlier in the year, the usual suspects immediately criticized the action as “authoritarian” and “typical of a communist regime.” A month or so later, Western democracies started to take similar lock-down actions enacted for even more extended periods. In fact, most countries, including developing nations, opted for similar measures. Indeed, Covid19 has no political affiliation nor promotes a specific ideology. So far, the evidence shows that such steps work. The virus spread seems to be under control in many countries, at least for now.

However, not all countries jumped into the same boat. Sweden is perhaps the most touted example here, continuously highlighted by mainstream media alongside those who look at the past as the only way forward – the future is the past if you can believe that. The government did take some action, such as limiting mass congregations and asking seniors to stay home, among others. But primary schools, restaurants and bars, for example, remained open on the assumption that locals were smart enough to avoid risky situations.

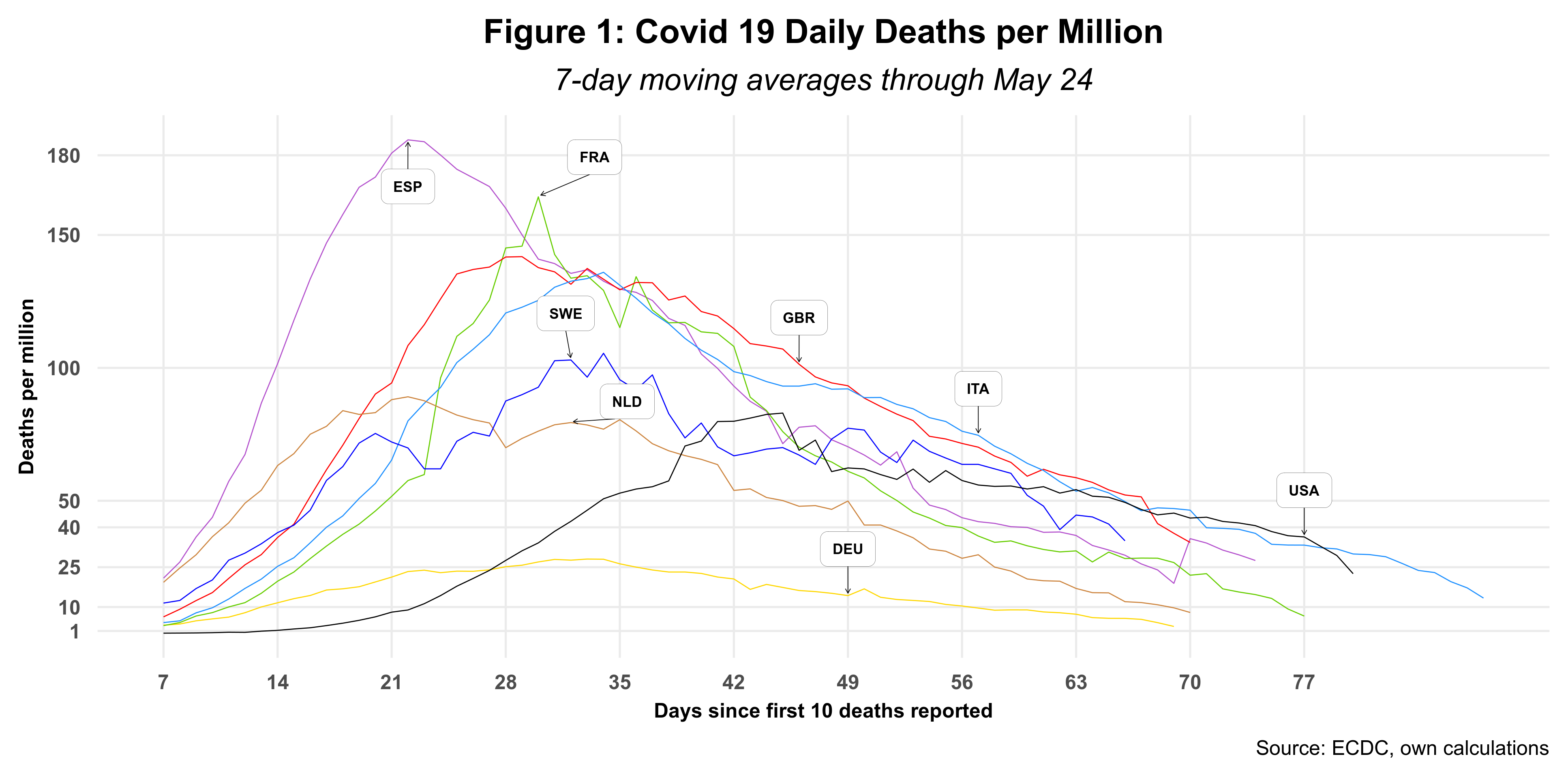

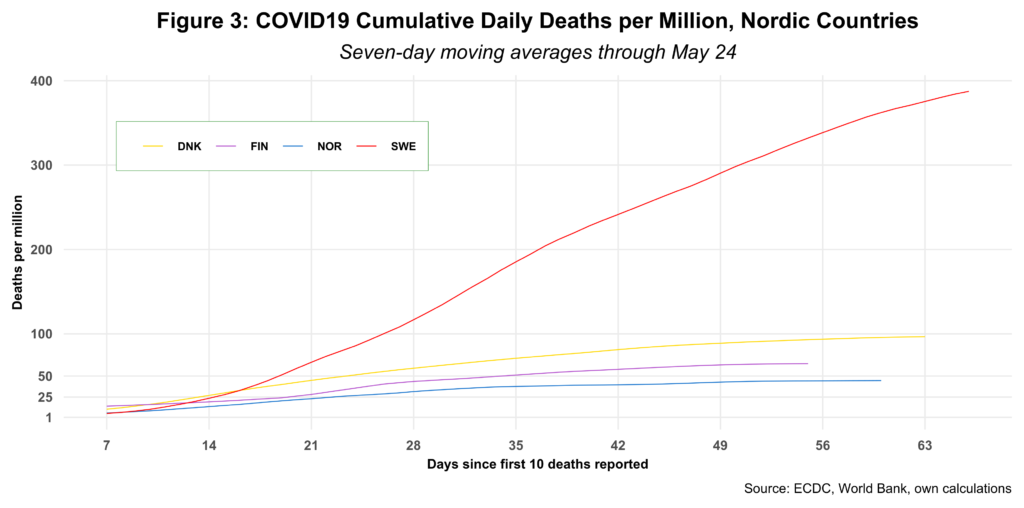

Is it working? Let us look at the data. Figure 1 below depicts the evolution of daily deaths per million inhabitants for eight industrialized countries.

Normalizing the data by population size is essential if the goal is to compare countries. Sweden has a population of 10 million that is eight times smaller than Germany’s and 1/32 of that for the US. A rapid upswing in deaths followed by a rather slow decline is the typical pattern for all these countries. After three weeks since the first ten deaths were recorded, Spain, the UK, the Netherlands and Sweden reported the fastest acceleration. By week seven, Sweden had already overtaken Spain and was just behind the UK and Italy. And by 24 May, Sweden had surpassed all other countries reporting the highest daily mortality rate – all now in decline. Germany, on the other hand, has had a unique evolution characterized by consistently low rates of mortality throughout the pandemic.

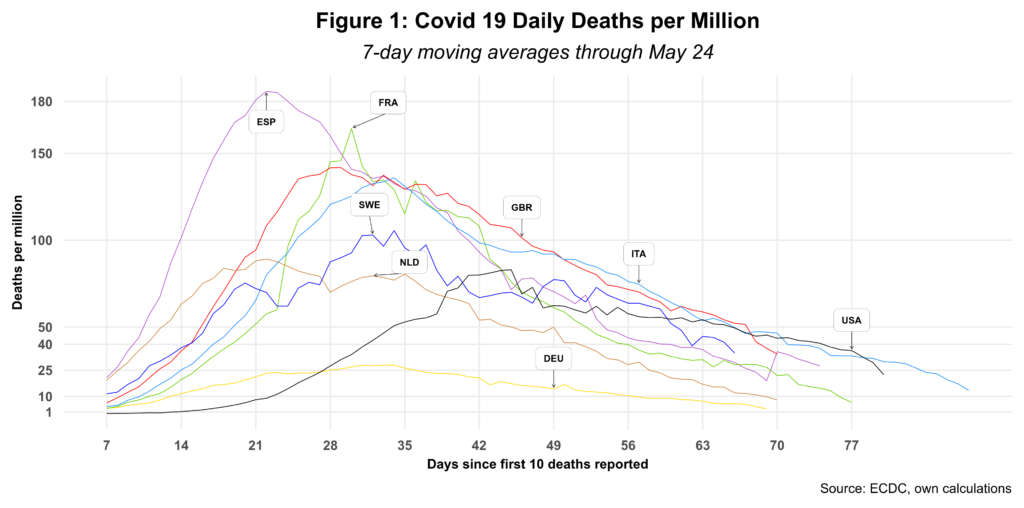

Figure 2 looks at the evolution of cumulative daily deaths per million inhabitants.

Clearly, Sweden is not the champion with the lowest death rate. That spot belongs to Germany. In fact, Sweden is about to overtake France for the 4th spot. Moreover, Sweden’s mortality rate deceleration is much slower than that for all other countries. Something is thus not clicking here, given Sweden’s government Covid19 policies.

Clearly, Sweden is not the champion with the lowest death rate. That spot belongs to Germany. In fact, Sweden is about to overtake France for the 4th spot. Moreover, Sweden’s mortality rate deceleration is much slower than that for all other countries. Something is thus not clicking here, given Sweden’s government Covid19 policies.

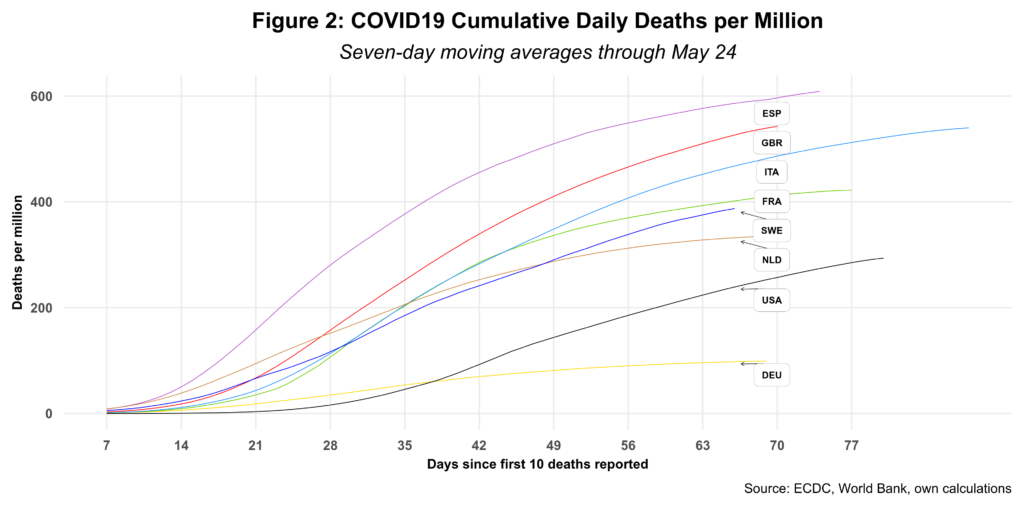

Figure 3 compares Sweden to three other Nordic countries, all of which adopted lock-down measures. The graph speaks for itself.

Compared to Norway, Sweden’s death rate is eight times higher (or 800 percent, to make it more dramatic). And Denmark’s it’s just one-fourth. Note also that these three Nordic countries are all well below the death rates of the countries depicted in figure 2 above, except for Germany. So perhaps we could speak about a German or a Norwegian model.

Compared to Norway, Sweden’s death rate is eight times higher (or 800 percent, to make it more dramatic). And Denmark’s it’s just one-fourth. Note also that these three Nordic countries are all well below the death rates of the countries depicted in figure 2 above, except for Germany. So perhaps we could speak about a German or a Norwegian model.

The other argument used to support Sweden’s “model” uses economics. In the medium-term, they say, Sweden will not experience a deep economic recession, unlike all others that adopted tougher Covid19 measures. Sweden’s economy is heavily reliant on exports, mostly to Germany, the US and the other Nordic nations. Now, all of the latter are currently undergoing a profound economic contraction. The demand for goods and services from Sweden (and all other countries) has thus dwindled to a minimum. Those working in these sectors will suffer. How about local small and medium enterprises that cater to locals? They might do better in the short-run than their counterparts in key trading partners but will eventually be hit by decreasing demand as the export and import sectors shrink thanks to the upcoming global recession.

Sweden is not racing ahead of anyone at this point. There is thus no such thing as the Swedish model. But If I had to choose a “model,” I would select Germany, Norway or New Zeland. A no-brainer for sure.

Cheers, Raúl