By all accounts, the ChatGPT “revolution” has triggered a well-deserved resurgence of Free/Open Source software (FOSS) that, some argue, will allegedly challenge the dominance of Big Tech over LLMs. While I disagree with such a prediction, I think FOSS can still play a vital role, as it did over 20 years ago, when facing the wrath of powerful, wealthy proprietary software companies and their millions of friends. But before diving into the recently rediscovered thermal waters, we should revisit FOSS—yep, once again!

FOSS

The so-called “PC revolution” of the 1980s (personal computer, not political correctness) was the opening shot in the massification of computing. While PCs were initially expensive, costs began to drop rapidly, and innovative devices such as laptops and, later, mobile devices proved to be decisive drivers. However, hardware alone was a necessary but insufficient condition for such massification. Software development was as important, if not more.

In the early days of computing, when mainframes and minicomputers dominated the scene, software was usually provided for free alongside the much pricier, typically large hardware. We can assume that the total hardware price included the cost of software development, undertaken in-house or through very select providers. That changed dramatically in the 1980s as the new computer architecture lacked basic software applications. Enticing programmers to develop PC software was thus part of the equation. As a result, software development started to boom.

Three software development models emerged at that point. First in line was proprietary software development, perhaps the most pervasive. This software is licensed to end users for a fee, and the maker does not share the source code. For entities with multiple users, proprietary software firms offered volume discounts and unit costs depending on the total number of users. Regardless, this model offered no free lunches, and those seeking one were systematically prosecuted worldwide. Freeware (not to be confused with shareware) was the second option. In this model, users were welcome to use the software for free, while end-user licensing agreements varied widely, depending on the author’s goals. Freeware was usually developed privately, and its source code was, for the most part, publicly unavailable.

The third model emerged in the 1980s: Free Software (FS). Here, the source code must be available to all users, who, in turn, have the right to modify, enhance, copy, distribute, and redistribute it, as long as their contributions remain part of the enlarged code base. This model comprises four fundamental freedoms that systematically capture the above. While FS has developed various licenses, the software can be used without paying any fees. In this light, developers from all walks of life were welcome to join if they endorsed the four freedoms. While private entities were welcome to use Free Software and modify it in-house, they could not repackage and license the new versions in the open market.

Such a restriction eventually led to the emergence of Open Source Software (OSS) in the late 1990s, as companies capitalizing on the first Internet boom, such as Netscape, found the Free Software freedoms too restrictive, thus preventing wider diffusion. That led to the creation of new and alternative software licenses that allowed FS commercialization. In any case, OSS is similar to Free Software and thus keeps access to the source code as one of its core traits (for the most part). What changed were the licensing schemes.

FOSS Political Economy

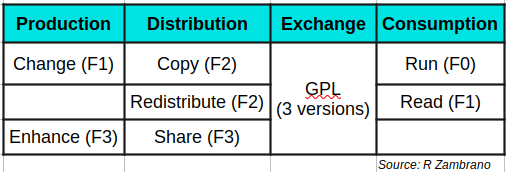

We can gain further insight into FOSS by using a Political Economy perspective centered on an overall production process framework—an approach I have previously shared. In this light, I mapped the four Free Software fundamental freedoms into the four core production process categories, as depicted in the table below.

Interestingly, the fundamental Freedom Zero (F0), stipulating that we have the freedom to use the software any way we want, falls under the consumption sphere. Access to the source code is not required. But perhaps its primary purpose is to allow end users to run the software for purposes beyond those initially set by its creators. And that probably requires examining the source code and doing a few coding tweaks here and there. Let us not forget that most end users cannot read computer code and are perfectly happy being regular consumers. That brings us to the fundamental Freedom 1 (F1), which allows us to read, study, and modify the code freely, thereby bringing consumption and production together. Here, reading should be considered productive consumption, as the objective is to understand the code and then change it in the production sphere. In F1, access to the source code is essential, with the caveat that most FOSS users cannot really read source code.

The distribution sphere is the target of Freedom 2 (F2), which allows users to copy and redistribute the original software. One could then distribute software executables (in binary format), the original source code, or both. In the consumption sphere, having the source code alone is insufficient to run the program. One must either compile the program locally, thus entering the production sphere, or obtain the executable files from another source via the distribution sphere. From the vantage point of consumption, F2 does not require access to the source code. The last fundamental Freedom (F3) brings together production and distribution. Unlike the production component of F1, here, we are free to add new features to the software, thus improving it. We must then distribute the new enhanced version to the whole community. These two steps are closely related and should not be separated unless the new coding is for private use only.

Note that the exchange sphere has not been part of the action, as the software itself does not have a price—albeit some might charge end users for associated distribution costs, including media, packaging, and shipping, for example—a common occurrence in the early days of the Internet. Nevertheless, unlike public domain software, Free Software has a copyright (called copyleft) that acknowledges creators’ contributions while preventing proprietary modifications to the code. It also offers a free General Public License (GPL) license that guarantees the four fundamental freedoms. These two fall within a peculiar exchange sphere where market prices play no role whatsoever. Instead, we get an exchange sphere for rights geared towards preserving freedom. In the case of OSS, we get an exchange sphere for benefits based on specific rights and responsibilities for software producers and consumers. But from the perspective of the consumption sphere, the difference between FS and OSS is zero.

According to mainstream economic definitions, FOSS can be categorized as a public good. Indeed, its consumption is open to all with no restrictions. Furthermore, actual end-user consumption does not reduce the pie’s size. The latter is a common trait of all digital goods that can be reproduced ad infinitum at almost no cost. The focus on consumption here matches FS’s first fundamental freedom (F0). So perhaps that is why it is first in the line of fire. However, by applying our Political Economy framework, examining the actual FOSS production process could yield more nuanced insights. I will suggest that FOSS is a public good because its actual production is open to all, with no barriers erected in principle. It resembles more “an association of free men (and women)” working together towards a single social goal that benefits society.

Nevertheless, to join the team of producers, I must have the necessary coding skills to read, study, change and modify the code. Most do not have such qualifications, nor are they eager to acquire them. So, in fact, only a few can join that team, thus potentially creating a gap between production and consumption. As FOSS consumers, we might receive software offerings that are irrelevant to our actual needs. On the other hand, coders are empowered and might even become benevolent dictators. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed person is king or queen.

Raúl