An Intergalactic Computer Network (ICN). That was the first Internet Imaginary in the early 1960s, used to depict the endless possibilities of the then-emerging network of networks. The ICN Imaginary was thus born several years before the first four academic computer networks were interconnected in 1969, thanks to the pioneering groundwork of IPTO and the ensuing ARPANET. While ICN has yet to materialize, efforts to build such a network are ongoing via the Interplanetary Internet initiative. Regardless, the crucial point is that the ICN Imaginary had a strong infrastructural perspective where hardware and software were dominant players, a far cry from the current “virtual” or “digital” Internet Imaginary. The latter was probably kick-started by Barlow’s Declaration of Cyberspace Independence.

1983 proved to be a seminal year for the emerging Internet. First, the few hundred interconnected networks adopted the recently developed TCP/IP protocols. Second, the military networks part of ARPANET declared their independence and moved to MILNET. Last, the Domain Name System (DNS) saw the light of day to handle the growing number of IP addresses and names on a distributed, nonhierarchical, resilient basis. That sounds a lot like modern blockchain technology. At any rate, TCP/IP and the DNS were technological innovations designed and developed to improve the effectiveness of the network’s ever-growing primordial computing infrastructure.

The importance of the DNS in the overall network architecture should not be underestimated. As the number of network hosts grew, the need for dedicated and specialized server capacity to cater to the continuous and rapidly growing ARPANET traffic became apparent. The first DNS root server was deployed in 1984, while the other 12 became operational within the next 15 years or so. Importantly, DNS root-servers are logical, as interconnected servers distributed around the globe and working in sync support each other. If one server or instance fails, another on the same root network will pick up the slack. The 13 logical root servers are designated by letters, from A to M.

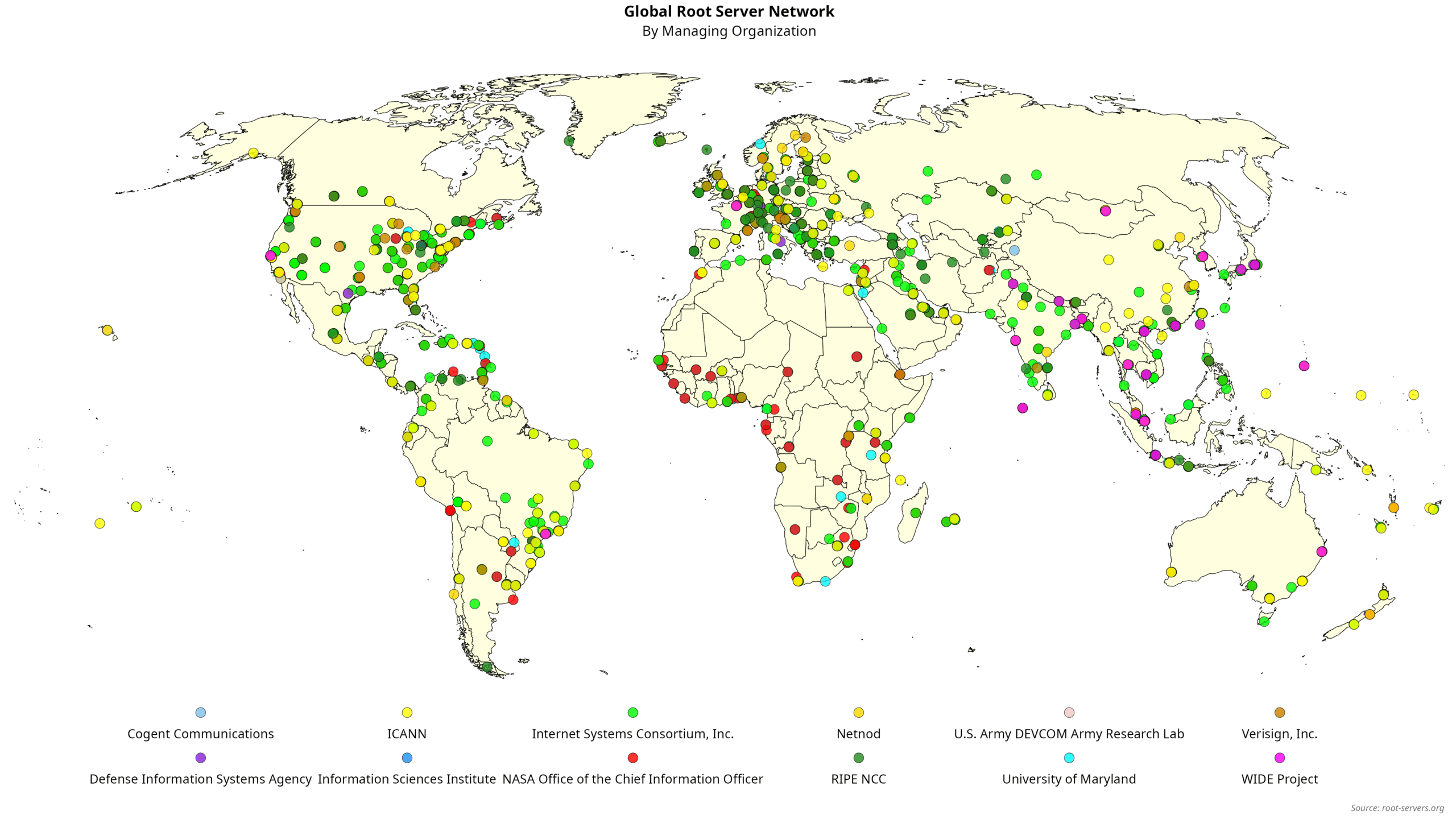

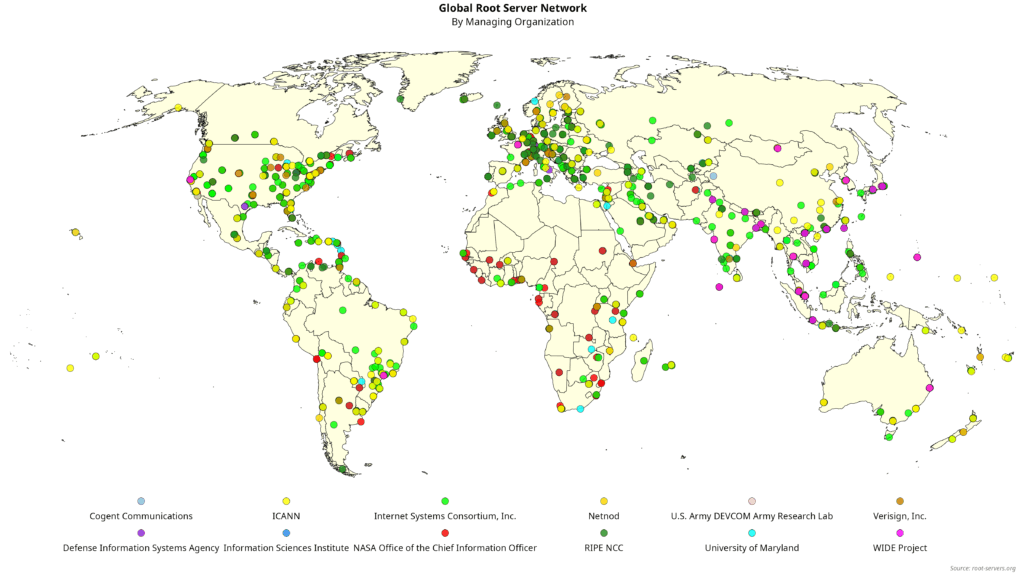

The map below depicts the global DNS root server network by the end of March 2025 (click to enlarge).

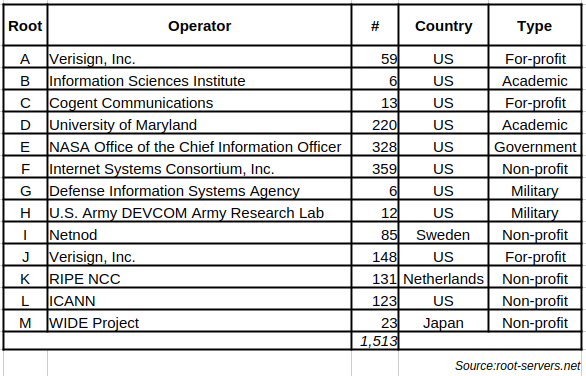

The latest data show that 1,513 servers (or instances) are part of the sophisticated root-server network distributed across 172 countries worldwide. The 13 logical root servers are supported by 12 operators. Verisign, a US company created in 1995, operates roots A and J. The table below summarizes the distribution of instances by operator, host country, and type.

Thus, US-based entities handle 86 percent (or 1,274 instances) of all root servers worldwide. The Internet Systems Consortium has the most significant node share of all operators, with 23.7 percent, followed by NASA (21.7%) and the University of Maryland (14.5%). Roots G and H are for the exclusive use of the US military, while Root B is entirely focused on academic research. On the other hand, Root C is also relatively small, as its operating company is an ISP. Note that none of the operators is hosted by a Global South country.

Moreover, disregarding Root allocations, 19.4 percent of all instances are in the US. Brazil is a distant second with 4.1 percent, followed by Germany (3.11%), Canada (2.84%), and India (2.78%). For example, Brazil hosts 62 nodes, and 73 percent of them are managed by the Internet Systems Consortium and ICANN. Interestingly, the US Army Research Lab has its own node in the country. Only 18 countries have a server share above one percent. That said, hosting an instance in a country other than the operator’s does not mean local entities get to run the show. While some flexibility is feasible, locals running such instances often do not have access to the servers, but are most welcome to reboot or decommission them.

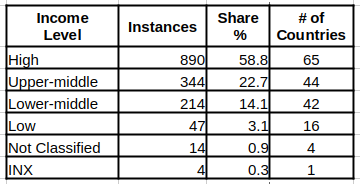

We can also examine the global distribution of root servers using the World Bank’s country income level classification, as shown in the table below.

Indeed, almost 60 percent of root server instances find a home in high-income countries, regardless of region (INX is the code the Bank gives to unclassified Venezuela, in case you are wondering). Thus, a positive correlation exists between a country’s GDP and its potential for becoming a root server host. This should not be a surprise, not at all. The same happens with the diffusion of most other digital technologies.

The non-profit Regional Internet Registries (RIRs), whose core function is to allocate IP addresses and Autonomous System Numbers, could be seen as a way to counterbalance the uneven global distribution of root instances. The existing five cover all continents, each based in its respective region. However, potential market size and income levels pose challenges for those catering mostly to middle—and low-income countries. Indeed, LACNIC and AfriNIC report the lowest levels of revenues when compared to the other three. The latter in particular seems to be facing daunting challenges. And recent geopolitical changes might not be the best of friends.

Raul