As previously suggested, the three core information categories proposed by the Information Disorder Framework (IDF)—disinformation, misinformation and malinformation—are not orthogonal. Indeed, a given message can change from one to the other as it rapidly flows through the Internet pipes, trying to feel at home in noisy, warm data centers. Clearly, what to an “evil” agent is undoubtedly misinformation might seem like plain and straightforward disinformation to me, as I might not know the agent or her hidden intentions. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that a plain falsehood is necessarily harmful. And so on and so forth. Such conceptual fuzziness leads to what I have called disinformation misinformation or misinformation disinformation disorder; take your pick.

Furthermore, translating these three categories into most other languages could be highly cumbersome and even impossible in some cases. IDF might then end reinforcing and even enhancing good old colonial mechanisms and neocolonial or post-colonial structures . By adding information layers and concepts unfamiliar to most people worldwide, IDF risks alienating most while adding pervasive random noise to an already polluted disinformation environment. We might end up moving from disorder to utter chaos.

IDF’s undeniable psychological traits open the door for deeming disinformation consumption as some sort of individual disease, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), for example. Not surprisingly, researchers have developed an approach to help “inoculate” consumers against unwarranted consumption. Here, “prebunking” takes center stage instead of the malicious intent of the information creator. The idea is to expose people to small doses of disinformation techniques to help them handle them better the next time and avoid manipulation. Prebunking is based on the so-called inoculation theory, and it offers an individual-based solution to a complex socioeconomic and political problem. I am not convinced that will work across the board.

Perhaps more surprisingly, media and communication academics have wholeheartedly embraced IDF. While that demands further research to explore possible rationales for such a bear hug, the experts I interviewed offered two possible responses. First, psychological approaches to propaganda and disinformation have dominated the field for almost a century, receiving strong endorsement at the height of Cold War 1.0. Alternative approaches, while available, have received much less support. Second, funding for disinformation research based on IDF seems to attract the most resources now. The latter brings us back to the question of how research agendas are established and promoted globally. However, that does not mean that we should not look for more elaborate analytical frameworks.

In fact, the IDF provides part of the answer and can thus be used as a departure point. However, it is standing on its head and thus needs to be inverted. Switching the focus from agents and interpreters to the macrostructures is vital. The framework’s three layers, each with three elements, can be simplified into three core components: information, actors and means. These, in turn, should be appropriately sequenced.

Information is the object that actors want to create, access, handle, and share for various purposes. In that scenario, disinformation is simply false information, regardless of whether the agent handling it is aware of this fact. Potential harm is a function of its diffusion across digital and analog networks. It thus depends on the degree of reproduction across the networks. Digital information can be reproduced at minimal cost and therefore diffused at accelerated rates. False information can thus easily spread globally in minutes in the digital age. GOFAD (Good old-fashioned disinformation) must be highly jealous of such wondrous capacities!

Actors or agents can comprise a wide variety of people or entities, public and private, who aim to generate and disseminate disinformation for specific purposes. In the digital age, critical is the creation of broad networks of actors and the subsequent emergence of networks of networks, or internetworks (of people, not computers and servers like the Internet). In most cases, disinformation is created and disseminated in such a way. Influencers are a great example here where one individual can have access to multiple networks globally, shape public opinion and set trends while making millions in the process . Spreading disinformation is also part of the job description if audiences increase as a result. More advertisement revenue comes their way.

In any case, such actors and networks must interact with existing information and communication means to achieve their goals, regardless of intent. In the case of digital disinformation, these means include the various networks and platforms, communication channels, and digital tools required to generate and disseminate it. Contrast that with GOFAD, where only states and a few private entities in the Global South could access such means. The monopoly over the means of information and communication was pervasive and strongly protected by high entry barriers and enormous costs. The Internet broke such a monopoly, removing many of them and massifying access—albeit creating quasi-digital monopolies along the way—thus triggering the so-called informational overload .

The essential point here is the interaction between actors and means, as that is the only way the former can generate disinformation and diffuse it efficiently. Focusing the research microscope on such interactions is crucial as they develop their own dynamics. This depends on the local context where specific political power distribution arrangements backed by well-established governance mechanisms are already in place, varying widely across Global South countries and regions. IDF touches on some of these elements but does not explore the interaction between agents and interpreters and the production and distribution of disinformation. It remains trapped within the micro level, constantly gazing at the behavior of the various actors, looking for all the answers there.

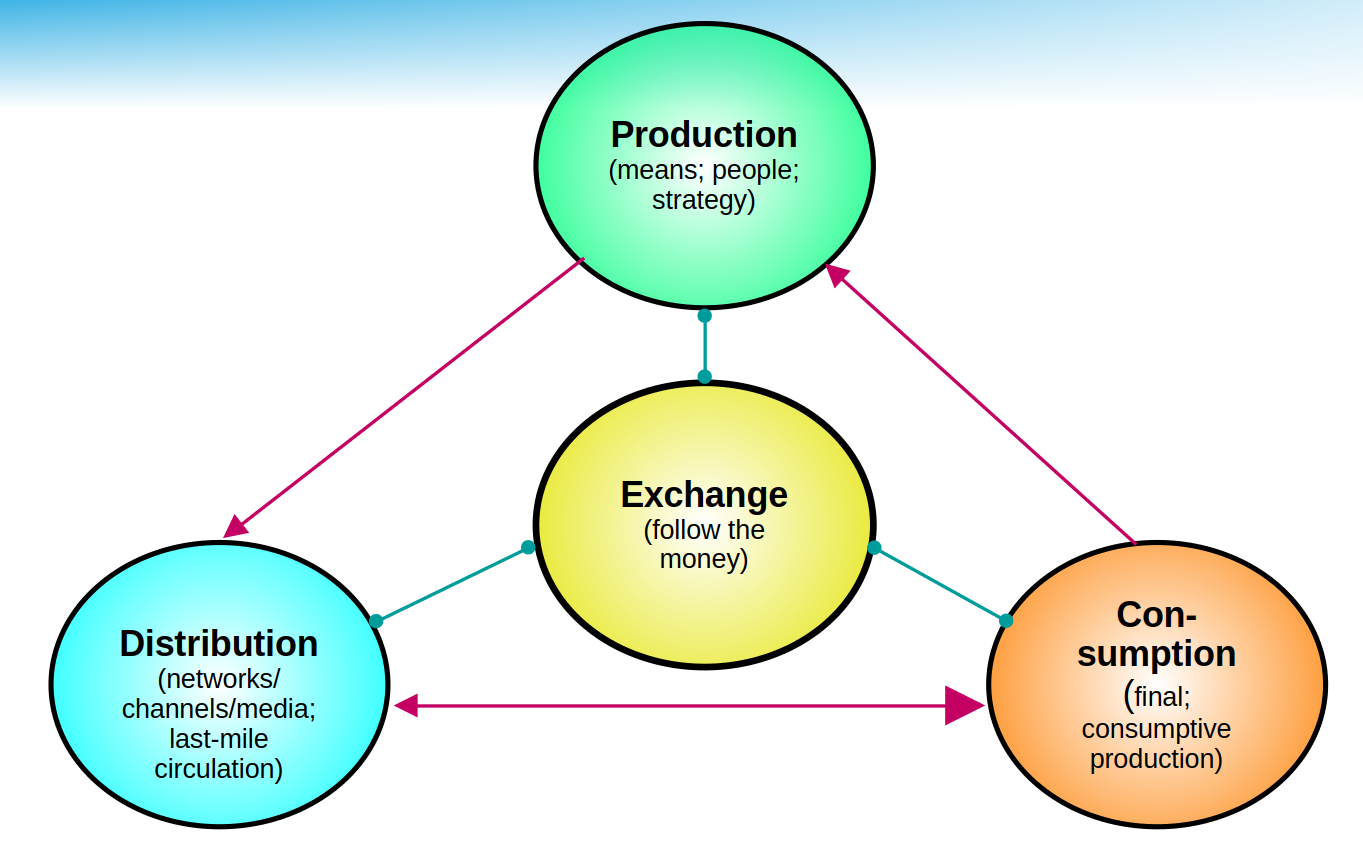

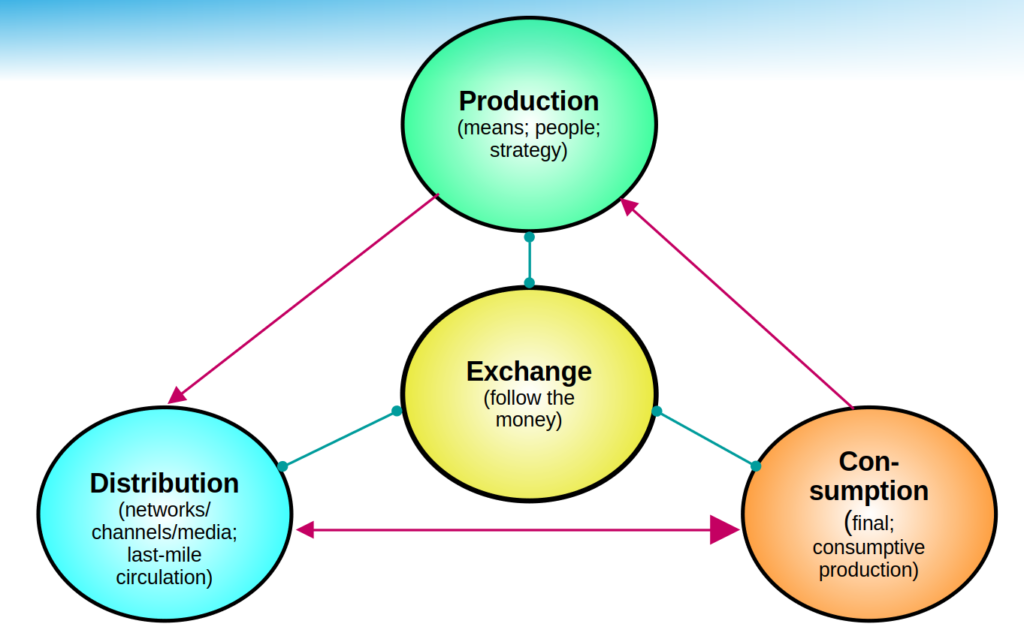

The political economy framework developed here takes the opposite approach. It focuses on the overall production process of disinformation, including distribution, exchange, and consumption, as well as production itself, operating within particular power contexts and governance structures. The latter usually precedes overall disinformation production but can also be heavily influenced by its diffusion. Indeed, successful disinformation campaigns might trigger the potential for power redistribution and governance reshuffles that those in power, with power or trying to gain it, often in intense competition, seek to achieve.

Production almost always demands investment in resources, including means of production (AI included if planned) and a team with a wide variety of skills. As with any information process, the strategic approach is vital, and disinformation strategists are a core part of it. Distribution has two components. First is access to the digital infrastructure that hosts the various platforms and communication networks that will help disinformation diffuse widely. Second is the circulation of disinformation, where technologies and actors such as trolls, influencers, and others ensure it travels quickly across networks and reaches final consumers—the so-called last-mile channels.

Consumption also has two interrelated facets. First, users who directly consume disinformation and take no further action on it. That is final consumption. The second is consumptive production, which has two components. On the one hand, passive consumers who click “like” or similar options to endorse disinformation, thus boosting bots, trolls, and influencers. Conversely, active consumers who redistribute disinformation to other networks, channels and platforms. The latter type of “interpreters” is crucial in this cycle. Exchange refers to the flow of financial resources within and between the other three layers of the production sphere. Figure 1 below depicts the structure of disinformation production described above.

Figure 1: Disinformation Order Production Structure

The actors, agents, and entities involved in the overall disinformation production process are embedded in local contexts shaped by power distribution schemes. They operate within the confines of well-established in situ governance structures and mechanisms, constantly exposed to unpredictable changes and systemic risks. Disinformation is a crucial catalyst here.

Entering the hidden abode of overall production unveils the Disinformation Order, conspicuously and comfortably living in the Information Disorder Kingdom. Undoubtedly, random disinformation is generated and distributed all around, especially regarding rumors, gossip, sarcasm, and humor (in many contexts, these might not even be considered false information ), and a few might even go “viral” and thus have a global reach.

But when it comes to big-ticket issues such as elections, public policy issues such as health and education, public opinion manipulation, climate change, racism and xenophobia, sexism and homophobia. They are usually supported by carefully planned and well-orchestrated networks of actors. They have ready access to the overall disinformation production cycle. Likewise, they can attract millions of “interpreters” and followers.

Indeed, the Disinformation Order reflects a governance disease that technologies alone cannot and will not solve .

Raul

References