Out of the five usual suspects frequently fingered as Big Tech gang members, Microsoft (MS) takes the top spot, time-wise. Indeed, the company turned 50 last April, beating Apple by almost one full year. Many will associate such advanced age with dinosaurs, especially if we use Internet time as a benchmark. However, MS shows no signs of slowing down—quite the opposite. Those half that age or thereabouts might not be familiar with 20th-century MS. That is certainly not my case. In fact, I had my fair share of direct interactions with the firm.

Envisioned initially as a software development company, MS serendipitously found itself in the right place at the right time. In 1980, it secured a contract with IBM, which was about to release its first personal computer (PC), to develop its operating system (OS). The company licensed an existing OS and hired a programmer to port it to the new IBM architecture based on Intel chips. The PC came out with a PC-DOS OS, while MS had its own version called MS-DOS. A couple of years later, several other companies entered the PC market, which was about to experience explosive growth. MS licensed MS-DOS to them, while PC-DOS remained confined to IBM machines.

That promptly led to the Wintel duopoly, which dominated the market for over 20 years. IBM was the big loser and eventually had to transform itself to survive into the 21st Century. In any event, trying to buy a PC or, later, a laptop without having Windows was almost impossible. I still recall arguing with PC vendors in the late 80s about getting a computer without Windows. Some even told me it was illegal, as “unbundling” was prohibited. There was no way they could ship one without having MS-DOS and, later on, Windows installed. Once Linux appeared in the early 90s, things only got worse. MS saw Open Source as its worst enemy and frequently called it communist when it was not a deadly cancer. My development project, which was to connect developing countries to the Internet, relied on Linux. We all became communists overnight, while aggressive chemotherapy could not save us!

The project soon caught the company’s attention. Sharp exchanges ensued, with MS directly addressing top UNDP managers, who, of course, had no idea about Linux or any other OSs. I was called to the front lines to defend the fort. I deployed a public goods perspective, arguing that Linux was a public good that supported UNDP’s core mandate: to enhance public goods provision in developing countries and augment human development. Moreover, using private goods like Windows or any other private OS would require us to launch a competitive public procurement process, like with any other private good, such as computers. However, if a matching public good were readily available at no cost, there would be no reason to start such a complex and unnecessary procedure. We also had project budget constraints.

MS had no response whatsoever to such an argument, but that did not stop them. In the mid-2000s, when we partnered with the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) initiative, which did not use Windows by design, MS’s CEO advised the head of UNDP to end the partnership. I was then asked to write an official response note explaining why that was not feasible or convenient for UNDP. Soon after that, MS made a 180 and started supporting Open Source. If you cannot beat them, join them, déjà vu.

By then, MS was already active in the gaming, hardware, mobiles, messaging, advertisement and cloud markets. Thus, it had evolved quite a bit in about 35 years. More recently, the company played a pivotal role in the success of ChatGPT by investing heavily and providing much-needed cloud access. That gave it an early advantage in the AI market.

The latest SEC K-10 annual report reveals that much, if not more.

“Microsoft is a technology company committed to making digital technology and artificial intelligence (“AI”) available broadly and doing so responsibly, with a mission to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more. We create platforms and tools, powered by AI, that deliver innovative solutions that meet the evolving needs of our customers. From infrastructure and data to business applications and collaboration, we provide unique, differentiated value to customers. We strive to create local opportunity, growth, and impact in every country around the world … As a company, we believe we can be the democratizing force for this new generation of technology and the opportunity it will help unlock for every country, community, and individual. We believe AI should be as empowering across communities as it is powerful, and we’re committed to ensuring it is responsibly designed and built with safety and security from the outset.”

Hyperbole aside, the company has clearly positioned AI as the driving force behind its operations. Thus, it follows the same path as its competitors—or gang members, as others will argue. Still, the company is razor-focused on two key offerings: cloud and related services such as consulting and support, and products including software (OSs and a wide variety of software applications, including games) and hardware (PCs, tablets, consoles, and accessories). The latest SEC report (2024) gives an initial glimpse at such a portfolio, as depicted in the table below.

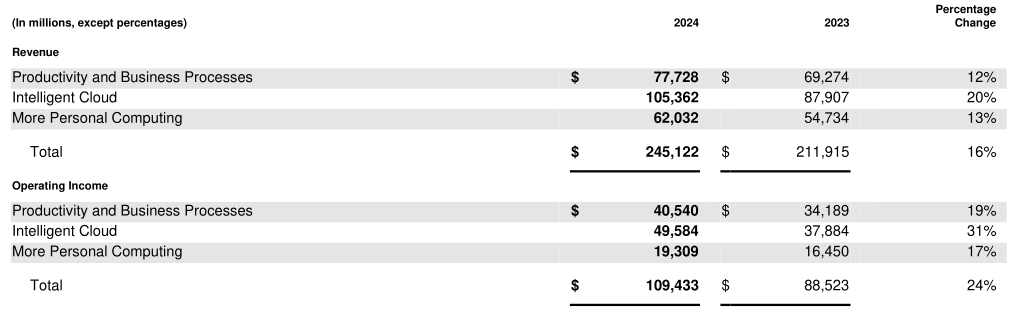

Productivity and Business Processes include Office, LinkedIn, and Dynamics 365, while More Personal Computing includes Windows, gaming, search, advertising, and devices. Cloud comprises Azure, SQL Server, Windows Server, Visual Studio, System Center, Nuance, and GitHub. The latter is the leading sector in revenues (43%) and operating income (45%). However, Productivity et al. report the highest rubric margins, with 52.2 percent, as it is mainly based on IP and subscriptions, thus demanding low fixed capital investments relative to cloud and other hardware investments. At any rate, these three categories encompass a diverse range of products and services.

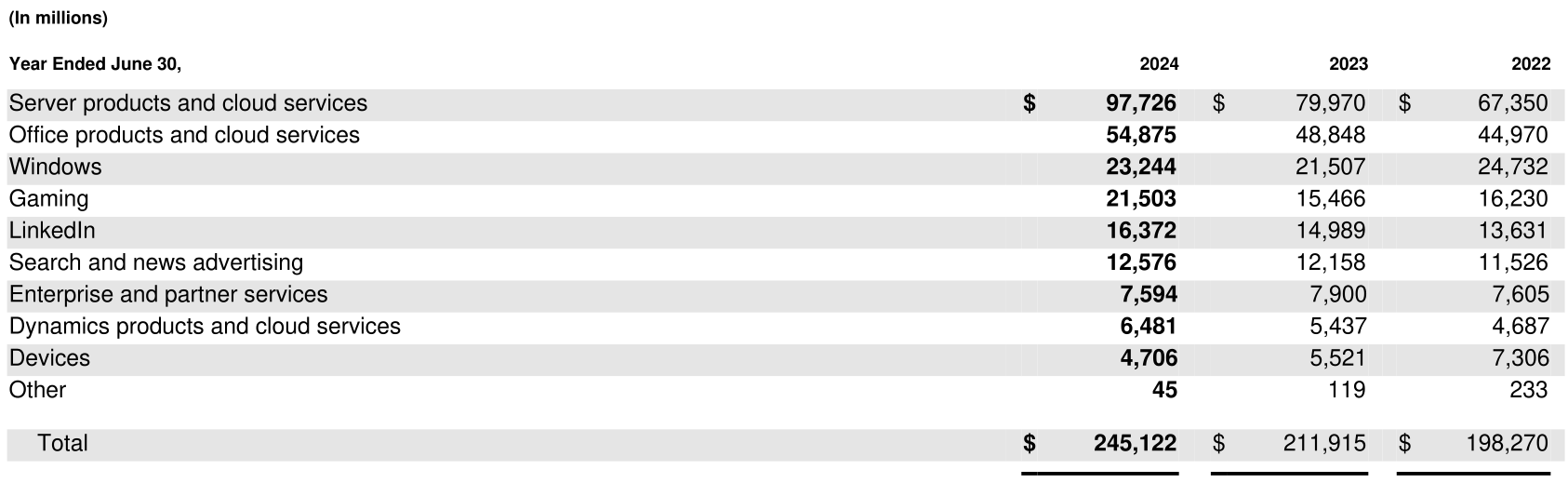

A better picture is provided by the table below, which classifies MS revenue by product and service.

Note that Windows accounts for less than 10 percent of all revenues today. On the other hand, the fact that cloud services, which account for 65% of all revenues (adding up the three related rubrics in the table), come on top once again can indeed be the result of new AI investments. However, now we are back in familiar territory, which I covered when analyzing other Big Tech team members. AI is primarily deployed to innovate and enhance existing products and services.

MS, however, is perhaps unique in this regard. Its core portfolio of services is based on software licenses or IP, not search, social networking, or mobile devices—although it also holds market shares in these areas. The secret ingredient here is integration. The example of Copilot is certainly illustrative. MS offers four versions, including a basic one that is free but requires an MS account. It works on Macs and mobile phones across all platforms. The Pro version has the exact pricing as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and is also readily available when using the free web versions of Word, Excel, and Outlook. The 365 version is fully integrated with all MS 365 products. The last one allows users to create their own copilots, customize the 365 version, and develop plugins to enhance it. Thus, the strategy is to deploy AI to improve existing core services and gain market share by outperforming the competition the old-fashioned way: continually introducing innovations.

MS is therefore much closer to Apple than to Google or Facebook. It also utilizes two-sided markets to enhance its core products and services, which operate in traditional markets. However, unlike Apple, the firm does not depend on producing manufactured goods. Its core business is in intangible knowledge, which is well protected by IP law. That has not changed since the late 1970s. In any event, MS is surely less exposed than Apple to market disruptions and unexpected tariffs. And yet, it cannot afford to ignore the competition.

Raul