Debates on the impact of automation on job creation are certainly not new. On the one side, we find those who argue that automation is the trigger for massive unemployment. On the other side are those who say automation can actually create more (and new) jobs. Historical evidence seems to show that both sides a right. In the short run, rapid automation does lead to higher unemployment levels. But if we look at the medium and long run, this is indeed not the case, at least not in all instances.

Debates on the impact of automation on job creation are certainly not new. On the one side, we find those who argue that automation is the trigger for massive unemployment. On the other side are those who say automation can actually create more (and new) jobs. Historical evidence seems to show that both sides a right. In the short run, rapid automation does lead to higher unemployment levels. But if we look at the medium and long run, this is indeed not the case, at least not in all instances.

How does this work? New jobs are indeed created not in the sector or sectors affected by rapid and massive automation. Rather, new jobs are created in new industries that previously were not relevant to the economy. A good example here is manufacturing vs. the service sector. While manufacturing today generates far fewer jobs than say 50 years ago, the service sector grew substantially in that same period creating millions of jobs worldwide. One could argue that the same happened when economies transitioned from agriculture to manufacturing. Nowadays, the number of jobs in the former is minimal, and we do not expect this to change any time soon.

The latest wave of automation is now taking shape in the form of robotics which in turn piggybacks on advances on artificial intelligence and the so-called machine learning. Ultrafast computing capabilities, cloud computing and cheaper storage, networking and massive access to new technologies among others are propelling this dynamic. Does this mean that every sector of the economy will now be automatized? Will the outcome of robotics automation be different this time around?

These are the questions that the book by Martin Ford (see end of this post for full reference) wants to address.

In the US, automation in manufacturing is now pervasive as its share of total jobs in the country is only 10%. But automation also has a positive income on jobs as it makes US manufacturing more competitive thus preventing further outsourcing to developing countries. However, automation is also taking place in such countries, so this potential benefit will depend on massive cost and technology competition.

jobs are really in the service sector which is now under threat by the new robotics “revolution.” First, it faces severe disruption by companies such as Amazon, Netflix, etc. which are capable of introducing automation at a faster pace. Second, the service sector could be fully automated by the introduction of intelligent vending machines and kiosks throughout. And third, brick and mortar sites now have the option to almost fully automate the services they provide to the public. Cloud robotics or the migration of robot intelligence to the cloud is facilitating these processes.

Ford argues that this time the process is really different due to 7 trends which have for the first time emerged simultaneously. These are:

- Stagnant wages

- Bear labor marker

- Declining labor force participation

- Less job creation, lengthy economic recoveries, and soaring long term unemployment

- Rising inequality

- Declining income and underemployment of new college graduates

- Social polarization and consolidation of part-time jobs.

These factors are also influenced by the globalization process, the financialization of the global economy and dramatic changes in politics represented by the overall decline of labor unions and the shift in US policies in detriment of the middle classes.

New Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are playing a fundamental role here. They are advancing exponentially vis-a-vis all other sectors and have already undergone several waves of innovation in the last 20 years. In fact, ICT has two key characteristics: First, it is a real general-purpose technology which means that it can function in any sector of the economy; and second, it also has “cognitive capacity” (pg. 73), as they can encapsulate intelligence which can, in turn, be easily replicated as distributed machine intelligence.

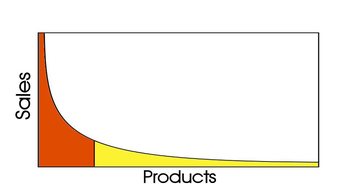

The two together generates what has been called a “long tail distribution” (or power law) that allows big ICT companies to get revenue at every point, regardless of the number of clients. Ford says this is indeed a trait of all goods and services that can be digitized. Indeed, this view will be conscientiously opposed by techno-optimists. But Ford also argues that there is little evidence that for example, mobile technologies have really helped the poor overcome their challenges, especially in developing countries.

The two together generates what has been called a “long tail distribution” (or power law) that allows big ICT companies to get revenue at every point, regardless of the number of clients. Ford says this is indeed a trait of all goods and services that can be digitized. Indeed, this view will be conscientiously opposed by techno-optimists. But Ford also argues that there is little evidence that for example, mobile technologies have really helped the poor overcome their challenges, especially in developing countries.

This brings us to a fundamental moral question: “Should the population at large have some sort of claim on that accumulated technological account balance?” (pg. 80), bearing in mind that much of ICT innovation has been publicly funded.

In sum, Ford is convinced that this time around automation in the form of robotics will harm society in both the short and long terms. In his context, we need to find new solutions that can provide “basic income” to the millions if not billions of people who will be unemployed in the future. And that solution is political, not technical.

Ford, Martin. 2015. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. New York: Basic Books. ISBN: 978-0-465-05999-7.