For a while, I have been planning on writing about the post-2015 High-Level Panel (HLP) report and the role of ICTs in the new development agenda. As I see it, the report has missed an ample opportunity here (as the old MDGs did!) by focusing primarily on one aspect of the new technologies potential to enhance human development. While in the 2000s, the focus was access to ICTs (and thus we got target 18 as part of MDG 8), now we have shifted to data, as in digital data.

While thinking about the arguments, I realized that further research and thinking was needed. First, I needed to fully understand what we mean by “data” and “data revolution” to link this to developing countries’ context. This led me to think about the broader concept of public sector information – not just data.

So here are some thoughts on all of this.

DATA

Simplifying things a bit for the sake of argument, we can define three distinct types of data based on how they are produced.

The private sector has always produced massive amounts of data for many reasons, one being the requirement to correctly read the market to dynamically adjust supply (and product creation) to cater to consumers’ specific demands. Real-time data is of particular interest here. At any rate, data produced in this fashion is private and accessing, if available to consumers, usually requires financial payment. In this sense, data here is just an average commodity like any other.

Governments also produce quite a bit of data. Think, for example, of civil and electoral registries, health and education data, etc. But public data is financed by taxes and other public resources and thus is, well, public. Therefore, it is a public good (non-rivalrous and non-exclusive) that should, in principle, be available to all stakeholders and citizens. Public data is thus not a commodity, in contrast to private data. And not all data produced by the public sector needs to be available to the public for various reasons.

Governments also produce quite a bit of data. Think, for example, of civil and electoral registries, health and education data, etc. But public data is financed by taxes and other public resources and thus is, well, public. Therefore, it is a public good (non-rivalrous and non-exclusive) that should, in principle, be available to all stakeholders and citizens. Public data is thus not a commodity, in contrast to private data. And not all data produced by the public sector needs to be available to the public for various reasons.

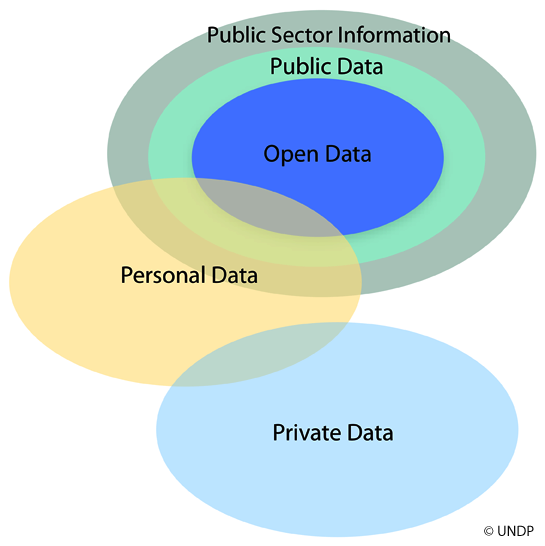

Finally, we have personal data or all the data (and information) that pertains to any natural person’s identity. This data is, so to speak, part of our personal DNA and has a direct relation to privacy. The latter is a fundamental human right acknowledged by the UN Declaration on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

PUBLIC SECTOR INFORMATION (PSI)

For the argument’s sake, I will briefly use the so-called DIKW pyramid (we can surely drop the Wisdom component!) to make a logical distinction between data and information. In this context, we can say that information is data processed and structured in some fashion that is useful for people to understand. Taking this at face value, we immediately realize that governments need to have information (not just data) to function effectively, issue policies and regulations and manage a country’s overall state of affairs.

We also need to point out that not all public sector information comes from data collected by the government or based on actual data. For example, OECD’s definition of PSI includes products, services, and data (see http://www.oecd.org/internet/ieconomy/40826024.pdf). The EU uses this definition and calls for PSI’s reuse within and across Union governments.

Based on the above, we can then say that public data is a subset of PSI. And open data can, at best, be as large as public data if we assume that all data created and collected by public institutions can be, in fact, be opened. This might not be the case if national security considerations are factored in, for example. Remember that private data purchased by the public sector for public use remains private -unless licensing agreements are spelled out to allow for its public, free-royalty sharing, and dissemination.

OPEN DATA

We can now say that open data refers to public data as a PSI subset. We have already noted that governments also process data to create information, which should also be open. So perhaps we can enrich the concept of open data by including public information in it. Or we can instead suggest the term open information, consisting of both public data and public information. This distinction is essential if we think, for example, of prioritizing which public information sets should first be made available.

Suppose the public sector already invests public resources to process data and generate information. In that case, making this information available and the data used to create it makes perfect sense. If private contractors are hired to process public data and contracts are not clear about the ownership of the generated information, it is then feasible that such information can become private and not be readily available to the public.

Freedom of information acts (FOIAs) and legislation actually targeted public information -and usually ignored data. Today, over 90 countries have already passed FOIAs. Most FOIAs exclude private information from their purview, so if public information is being privatized, there is no exact way to address this issue via FOIAs.

Finally, many countries are updating FOIAs to include digital information and data -although I cannot imagine the average citizen requesting a FOIA to access data per se. Adding digital information is critical as some governments can argue that FOIAs only apply to information on paper and not on a computer, in digital format.

Now, quickly glancing at how the Internet and other news technologies have impacted this, we can say there is a clear tendency to mesh the three different data types into one single and more significant set (see animation below). Think, for example, of big data, combined with how personal data has become much more public, especially with the advent of social networks. Personal data is being privatized on an unprecedented scale and sold like any other commodity. The same can be said about chunks of public information that are somehow bought by the private sector and is thus only available (if available) at a cost.

DATA, DEVELOPMENT AND REVOLUTION

The lack of reliable and official statistics for measuring MDG targets shows that many developing countries do not yet have the resources, capacity and/or political will to generate data and information relevant to national and international development agendas. MDG Acceleration Framework (MAF) reports conducted in the last 3 years have provided additional data on the MDGs. However, data gaps remain considerable after a quick review of many of them.

There seems to be a clear need for a “data revolution,” as suggested by the post-2015 HLP. But what the HLP has in mind goes beyond measuring and monitoring development progress. The panel also calls for a “new data revolution” for accountability and decision-making processes, capturing citizens’ demands, reaching the neediest, assessing public service delivery, providing open access and supporting statistical systems (see HLP report pgs. 23-24). Note that the HLP does not refer to big data and uses “open data” as two separate words – and not as the concept we discussed in the previous section. Finally, the HLP also calls for a “Global Partnership on Development Data” that should include all stakeholders, sectors, and interested parties.

Going back to the issues raised in the previous section, it is possible to argue that what we are really talking about is a new information revolution. The difference with the one in the 1990s is that many more people, millions if not billions, have access to information and communication channels and can thus access information and provide information interactively and in real time. After all, this is the major difference between the new technologies and radio or TV, etc.

I am not too sure I understand the concept of development data. Most PSI is relevant for the development of poor countries (LDCs, LICs and many LMICs) and is indeed a requirement to make integrated and evidence-based policy decisions. This is certainly not the case with countries in the upper brackets of development or income. There is no single definition of development data in this light, as it can vary across different contexts. It is probably better to stick then to PSI relevant to development while fostering participation, transparency and accountability.

Cheers, Raúl