GDP: Thanks, but no thanks

A recent issue of The Economist had a couple of articles (plus the issue’s cover) on measuring prosperity, defined as advancing living standards over time. Nowadays, gross domestic product, GDP,1 We can also include here GDP’s sibling, Gross National Income or GNI. is king for measuring such progress. However, The Economist argues that GDP is not the best indicator for accomplishing this. Unlike the 20th century, the issue today is that while GDP is still growing at a regular pace, albeit not as fast as in the past, living standards seem to be stagnant, thanks in part to rising global inequality.

This unintended divorce between GDP and living standards highlights the quality of goods and services people consume and use over time. GDP assumes their quality is constant. However, if we peek around, we notice that, say, the quality of cell phones and laptops has increased over time while real prices have, in fact, declined in that time span. 2 The same goes for “free” services such as Google and Facebook. However, this is related to the much older debate on how to measure the output and value-added of the nonprofit sector in national income and product accounts. So, while GDP adequately captures the latter, it does not say anything about the former. GDP thus needs to be retooled, though not scrapped altogether.

GDP-plus and Human Development

One of the options to improve GDP offered by the publication is to create a new indicator called GDP-plus, which measures both “…unpaid work at home…” and “…changes in the quality of services by, for instance, recognizing increased longevity in estimates of health care’s output“,3 The Economist. 30th April Issue, page 7. among other things. It now includes some non-economic qualitative areas that can have considerable weight when measuring human well-being.

Reading this, I realized it did not ring as strikingly new. I am familiar with the Human Development Index, HDI, which has been annually published for the last 25 years by the Human Development Report Office of the United Nations Development Programme, UNDP. Its latest 2015 incarnation deals with the issue of unpaid work and dedicates prime time space to the subject – linked to the gender dimensions of the topic.4 For an overview of the HDI and a basic definition of Human Development, click here.

On the other hand, longevity has been an integral part of HDI since its inception. However, the HDI gets no space, prime time or not, in the Economist’s analysis.5 But the publication has repeatedly covered the HDI in the past. See, for example, http://econ.st/21W9ZoA, http://econ.st/1TAbnHx, and http://econ.st/21W9H1b.

HDI Plus?

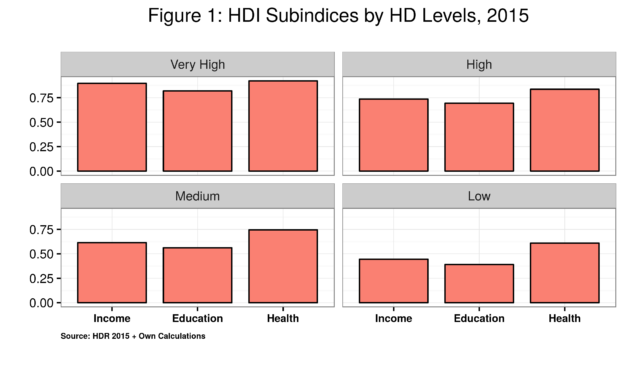

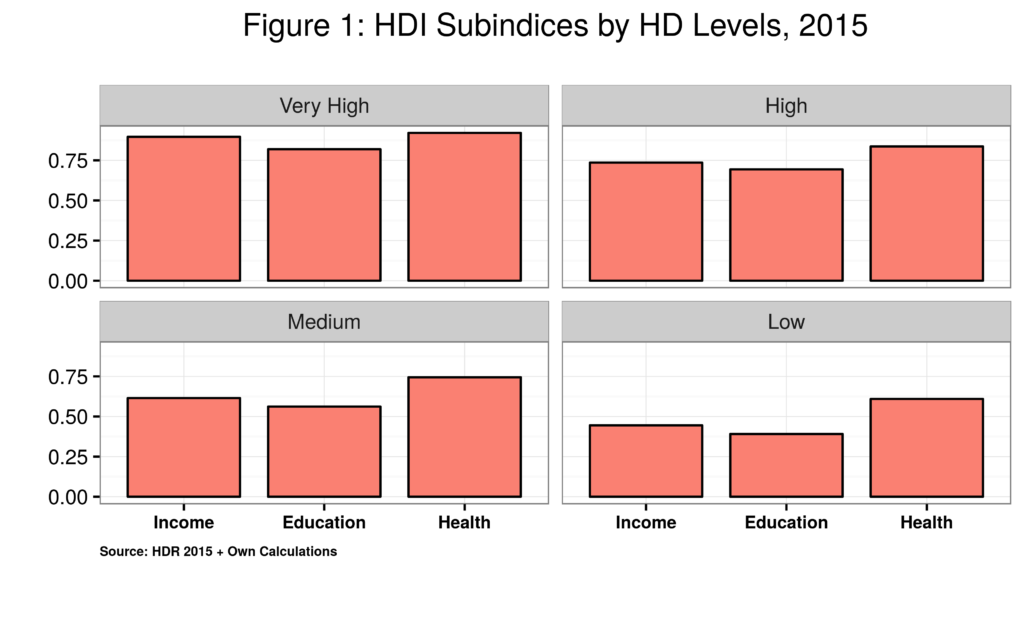

The HDI is a composite index of three key human dimensions of well-being: income, education and health. It uses four indicators to estimate human development: Gross National Income, literacy and average years of schooling for education, and life expectancy for longevity and health. As we can see, the HDI is, in fact, a close relative of GDP as it uses its sibling, GNI, as one—but not the only—of its core indicators.

One of the main highlights of HDI measurement is that a country can have a large GNI per capita but a relatively low HDI score. Intuitively, this makes sense as GNI only accounts for a portion of the total index. Typical examples here are oil-exporter countries that can generate large GNIs in the short run but lag in education and health, which can be slow-moving parameters across time.

Figure 1 below depicts the relationship between the three main subindices that comprise HDI by levels of human development. Note the correlations between HDI levels and the three indicators. Health, in particular, shows a unique pattern, which I will explore in another posting.

It goes without saying that, just as GDP, the HDI has been subject to a series of criticisms over the years, ranging from substantive to statistical.6 We will not dwell on this here. Check the list of selected references below to see some of the main critical perspectives. And since it also includes GNI, it is also an indirect recipient of all GDP related criticism.

The HDI seems to have already done some of the groundwork required to propel the proposed GDP-plus.

So why not link the latter to the former?

Raúl

Selected References

Klugman, Jeni, Rodríguez, Francisco, Choi, Hyung-Jin, 2011. The HDI 2010: new contro-versies, old critiques. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9 (2), 249–288.

Kovacevic, Milorad. 2010. Review of HDI Critiques and Potential Improvements. HDRO Working Papers. New York: UNDP. http://www.hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdrp_2010_33.pdf.

Merwan H. Engineer, Nilanjana Roy and Sari Fink. 2010. “Healthy” Human Development Indices. Social Indicators Research, 99 (2), 61-80.

Philipsen, Dirk. 2015. The Little Big Number: How GDP Came to Rule the World and What We Can Do About It. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ravallion, Martin. 2012. Troubling tradeoffs in the Human Development Index. Journal of Development Economics, 99, 201-209.

Wolff, H., H. Chong and M. Auffhammer. 2011. Classification, Detection and Consequences of Data Error: Evidence from the Human Development Index. Economic Journal, 121, 843-870.

Endnotes

| ⇧1 | We can also include here GDP’s sibling, Gross National Income or GNI. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | The same goes for “free” services such as Google and Facebook. However, this is related to the much older debate on how to measure the output and value-added of the nonprofit sector in national income and product accounts. |

| ⇧3 | The Economist. 30th April Issue, page 7. |

| ⇧4 | For an overview of the HDI and a basic definition of Human Development, click here. |

| ⇧5 | But the publication has repeatedly covered the HDI in the past. See, for example, http://econ.st/21W9ZoA, http://econ.st/1TAbnHx, and http://econ.st/21W9H1b. |

| ⇧6 | We will not dwell on this here. Check the list of selected references below to see some of the main critical perspectives. |