Knowledge to master innovation, innovation to augment our stock of development knowledge

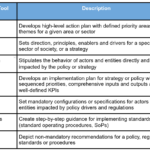

1. Earlier this year UNDP approved a new KM strategy which has 6 pillars: Organizational Learning and Knowledge Capture; Knowledge networking; Openness and public engagement; South-South Cooperation and External Client-Services; Measurement and incentives; and Talent management. Note the last three items which seem to crossover to other areas or work of UNDP and HR management. This is fine as long as those areas have similar components in their own strategies -although they seem to be a bit out of place here.

2. A fresh reading of the document suggests that one of the pillars for the new KM strategy was Teamworks. Seems that nowadays corporate thinking has evolved and TWs will most probably become part of BOM and be aligned with SharePoint. Pillar 3 will however be maintained but that does not have to depend on a single platform.

3. While TWs was a good idea in its day, its implementation left much to be desired thanks in part to the technological approach taken by the KM team leading the process. For example, software development became a priority, one that consumed lots of financial resources as well as UNDP capacity to consider core KM issues that, for example, BDP advisors globally faced in their daily work.

4. Any KM strategy must ensure that we clearly separate the technology from the actual core KM pillars so that bottlenecks and challenges are addressed effectively. And technology is excellent for the latter, that is, to help solve in innovative and transformational fashion core KM issues and challenges. This was the main issue with TWs which essentially failed to do this, overemphasizing instead its social media nature and potential.

5. Being that as it may, the critical issue for any KM strategy is not the why one is needed and what areas should it cover but rather how can it make an overall difference in UNDP. Needless to say, KM must adjust to the 7 broad outcomes of the new strategic plan. That is almost tautological. But the core question is how can KM help UNDP staff achieve such outcomes in effective and dynamic fashion, bearing in mind that policy areas are not static but rather continue to evolve on an almost permanent basis. In 4 years for example, inclusive growth will have moved quite a bit from what we have today as more knowledge will be be created and more experiences will be accumulated and shared. We are indeed referring to moving targets and thus any KM strategy should be capable of hitting such targets on the fly, so to speak.

6. One key element that UNDP should consider is the effective introduction of KM into the policy and programme cycles. That is, bring KM into the current policy and programme work we do while at the same time trying to transform such cycles in innovative fashion and reflect for example changes that need to take place in order for us to be on the leading edge of policy development and programme implementation. KM thus comes to these cycles and not the other way around; do not force the cycles into KM. Evidence suggests that this is certain to bring failure.

7. People are at the center of any KM strategy – in this case UNDP staff. Traditional KM was based on individuals that happen to have tacit and explicit knowledge. But nowadays with the explosion of data and information, knowledge is distributed around the edges of the network. Collaboration among individuals is thus key to ensure knowledge is manged effectively. With this in mind, UNDP should consider creating Collaborative Knowledge Communities working on a global and interregional basis and replace traditional communities of practice.

8. The emergence of data and big data has also changed KM. While in the past knowledge was seen as processed and distilled information, data has substantially augmented the scope of KM as potential knowledge is now not only in the heads and pens of experts but is also sitting on a global networks where billions of billions of data points are captured on a daily basis, awaiting to be transformed into information and knowledge. And this also needs to be effectively managed. New skills sets are thus needed by UNDP staff to able to tap and manage this vast potential knowledge resource. This is also an important component for any policy approach that claims to be based on real evidence. Again, this is not about big data per se but rather about the capacity to harness data to create new knowledge and bring it into the policy and programme cycles.

9. It is surprising that after the heavy investments on TWs and technology, UNDP lacks basic platforms and applications to share and manage documents, to work collaboratively on knowledge products, to effectively manage rosters and knowledge databases, to run statistical packages to analyze data and detect trends and gaps, to create multimedia products and infographics, and so on and so forth. In other words, we are lagging behind when it comes to basic KM tools while we have a seemingly complex social media site. TWs. UNDP needs to revisit this and BPPS should work with BOM to ensure this tools and platforms are available to all staff. A return to basics is needed here. And a serious reconsideration on TWs is also required – noting also that TWs user demand is still on the low side of the equation after almost 5 years of operation.

10. While there is not corporate innovation strategy in place, work in this area has been moving fast in the last couple of years, essentially led by the now defunct Bratislava Regional Service Center. While uptake of such efforts have been very successful in that region, the same cannot be said about all others. Discussions of why this is the case are still ongoing, noting the specific history of RBEC in terms of local capacities and democratization processes.

11. In any event, early success has brought UNDP a new infusion of resources which are now sitting on a programme managed by BPPS, and currently being disbursed to countries offices. An Innovation Facility has been set up and already earmarked 2.5 USD to support facilities in COs, with over 1 million alone going to Africa. In addition a campaign called SHIFT has been launched to support the Social Good Summit that UNDP has been sponsoring for the last couple of years. Countries offices have been asked to submit expressions of interest to compete for small grant allocations

12. Innovation is a hot topic nowadays in the development agenda. Most UN agencies and multi-laterals are implementing innovation-related activities. In a sense, the topic has been de facto hyped and competition among agencies for funds and programmes is intensifying. In the midst of all this, UNDP is faring relatively well so far.

13. Innovation is similar to KM, to a point. Since UNDP is not an R&D or S&T outfit, innovation cannot be the end goal of our work. On the contrary, we need to harness innovation and innovative approaches to enhance and deepen our development work and thus generate more state of the art knowledge in our core competency areas. But innovation in UNDP needs to also be well aware of the decentralized nature of the organization and the pivotal role that Country Offices (Cos) play in the policy and programme cycle.

14. Based on my experience of dealing with over 100 Cos, we can identify three types of staff in UNDP when we see them under an innovation lens. First, 5/10 percent who can be considered true innovators per se and have found the corporate space to freely operate in innovative fashion without lots of bureaucratic constraints. Second, 20/30 percent who can be defined as knowledge brokers who are aware of the latest developments that impact their own areas of work (innovators outside UNDP, inside their countries of operation) and who can then make use of them (via out sourcing) as needed. And third 60 percent or more who are essentially focused on their areas of work and do not have the time to consider changes inside their portfolios due to work load or local constraints. The exact composition can vary from country to country but in general UNDP is not really geared for quickly introducing innovation within its staff, not without having to change some of the constraints we face inside the house.

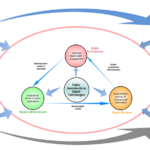

15. We should also consider three key layers for innovation work: 1. Corporate innovation which is essentially bringing changes in the processes and procedures that we use to run the organization itself; 2. Innovation in development programming which allows UDNP to advise programme countries on how to harness innovation to accelerate or stimulate development agendas and development programmes; and 3. Innovation within CO which is a mix of the first but also has s the distinct component of bringing new approaches to UNDP programme design and implementation.

16. Needless to say, these three layers overlap. If we think about them as circumference sets, we will have an intersection where the three of the share a common area. That common area is the place where innovation efforts should start as the direction the efforts can take will depend of the strengths and weaknesses of each of the three different sets. This common area is also what allows innovation efforts to sync up across the house. In the case of UNICEF for example, innovation started here but initially found the space needed to grow in the developing programming set to then move to corporate innovation and finally to UNICEF COs. While UNICEF´s experience might be unique it is important to learn from it (talking about KM here!).

17. The influence of NESTA in UNDP’s approach to innovation has been strong to the point that our whole language and approach seems to be derived from them. Issues such as prototyping, design thinking, complex thinking, etc. are indeed important. But UNDP needs to factor in the issues raised above. As with KM, we cannot force our policy and programmes cycles into innovation approaches. On the contrary, we need to bring innovation into the former.

18. A lot of the activities we are now doing under innovation, especially when it comes to using new technologies, have been done in the past by the organization at the global, regional and national levels. As a matter of fact, UNDP is one of the pioneers in bringing ICTs into development agendas and programmes and this usually implied bringing innovative approaches to address tradition development gaps. Any UNDP innovation strategy must factor these experiences and learned from them (again, we need more KM here too!).

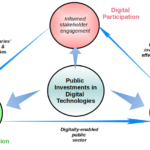

19. One critical innovation element that UNDP seems to be mission for innovation layers 2 and 3 mentioned above is experimental design. With experimental design, which is now used by many development organizations, WB included, we can in fact show how innovation and technology can cause real changed on the ground. It is not just about pilots or prototyping. It is also about ensuring public investments on innovation and innovations have the desired effect on development outcomes and we have the real evidence handy to both advise policy makers and design effective development programmes.

20. Innovation is thus also a trigger for generating additional development knowledge which will in turn demand a fully functional KM strategy that can effectively handle the ever expanding development knowledge stock.

Cheers, Raúl