The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) has recently published the latest iteration of its democracy index. The biggest headline about the new EIU report was the demotion of the US from “full” to “flawed democracy”, complemented by the medium-term decline of democracy in Eastern and Western Europe, and in North America. The latter is based on trends that first emerged a decade or so, according to EIU. Even so, Norway continues to take top prize while North Korea seems to be persistently stuck at the very bottom of the rankings.

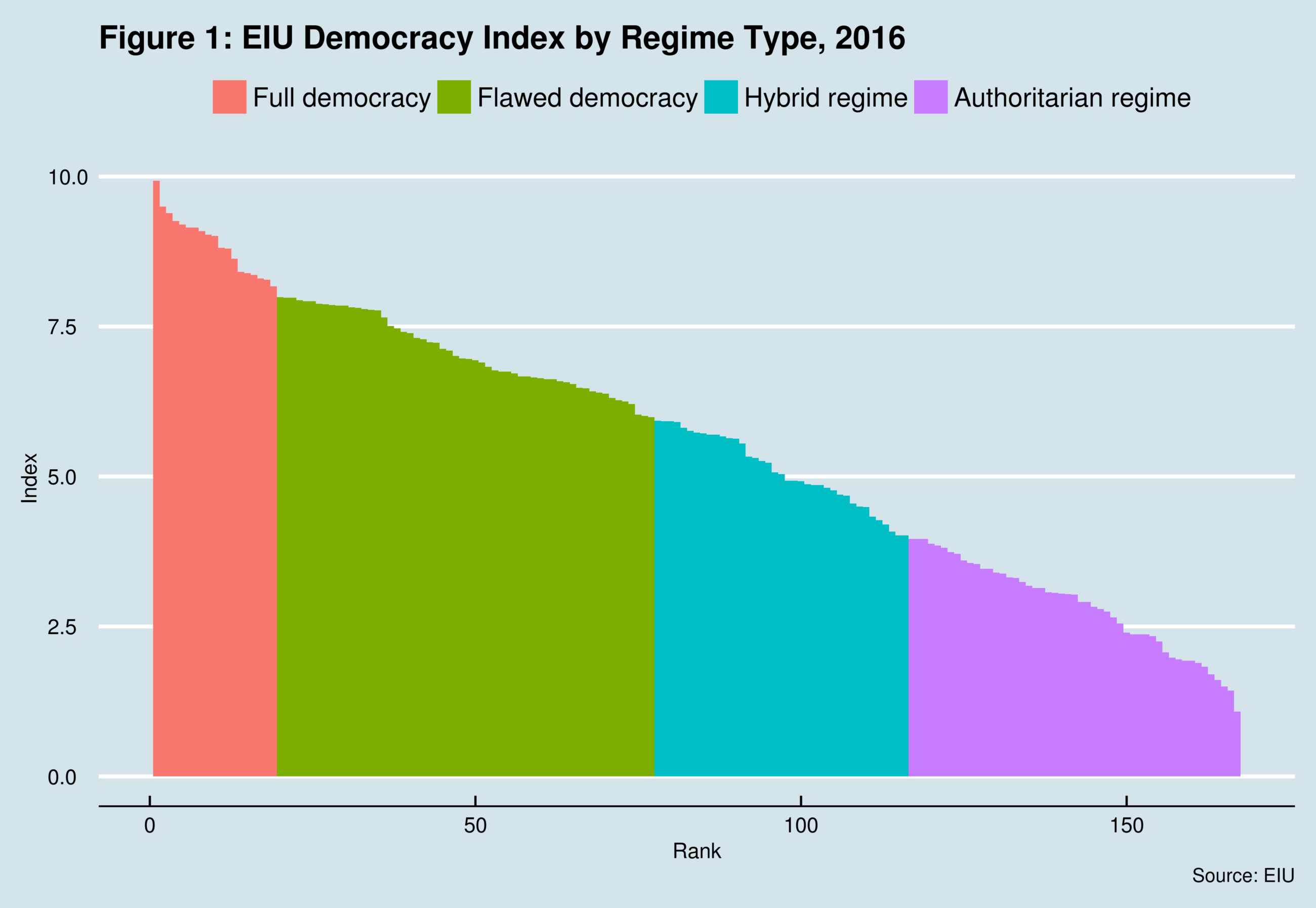

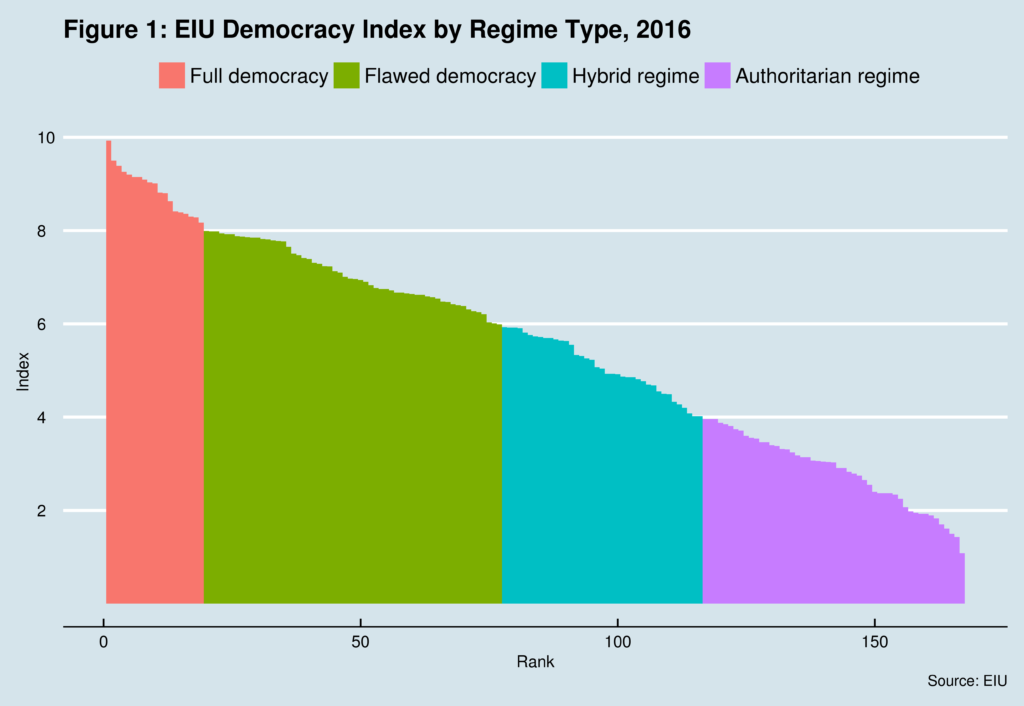

Figure 1 presents the overall distribution of the 167 countries that the report covers. Flawed democracies are the most common type of regime, followed  by authoritarian countries. In fact, full democracies only account for 11% of the total, while hybrid and authoritarian regimes together comprise over 54% of all countries included in the report. Democracy is thus not really spread globally as it is usually assumed.

by authoritarian countries. In fact, full democracies only account for 11% of the total, while hybrid and authoritarian regimes together comprise over 54% of all countries included in the report. Democracy is thus not really spread globally as it is usually assumed.

Note also the spread of the index itself: For example, Norway’s index score is about 9 times larger than that of North Korea. The democracy ladder thus seems to have a long and steep climb. This in turns suggests that moving up and down the index rankings is a slow moving process unless countries face revolutions, civil war and/or violent conflict, or a coup d’état, among other major political events.

Indexing democracy

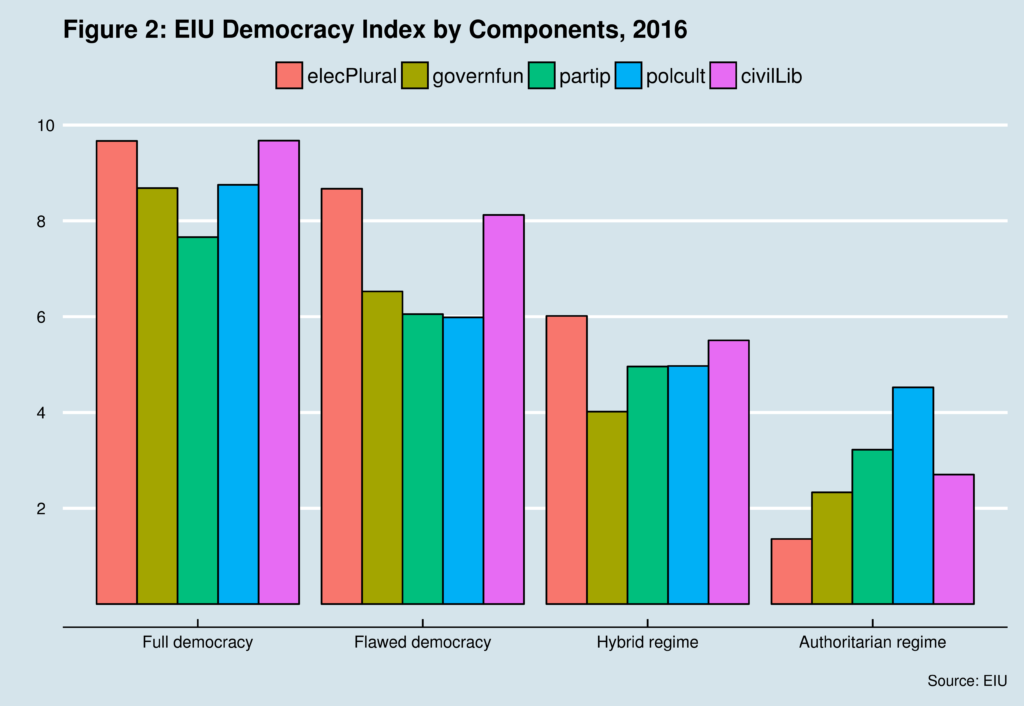

While a universally accepted definition is difficult to find, the EIU identifies five core pillars that can help characterize democratic regimes. These are 1. Elections and pluralism; 2. Functioning of government; 3. Political participation; 4. Political culture; and 5. Civil liberties. Using experts assessments as well as data surveys from various sources, each component is scored from 0 to 10.

The democracy index is the simple average of these five components. Countries scoring above 8 are considered full democracies. Those under 8 but above 6 are flawed democracies while hybrid regimes range between 4 and 6. All those below 4 falls under the authoritarian category. Unlike full democratic regimes, flawed democracies have a weaker government, political participation, and political culture.  Hybrid regimes, in turn, have difficulties holding fair elections and are permeated by pervasive corruption. Finally, authoritarian countries have serious gaps in all the categories with some being well-recognized dictatorships.

Hybrid regimes, in turn, have difficulties holding fair elections and are permeated by pervasive corruption. Finally, authoritarian countries have serious gaps in all the categories with some being well-recognized dictatorships.

Figure 2 shows the average scores for the five components for each of the four regime types. As expected, they are in sync with the EIU regime classification. One interesting feature of democracies, both full and flawed, is the relatively low levels of political participation, a component which has the lowest score in full democracies, even below the threshold for such type of regime. And it is second to last in the case of flawed democracies.

This is in sharp contrast with the other two type of regimes where political participation is relatively more relevant, given the fact that the other components score low. On the other hand, elections and pluralism, and civil liberties are the two most important components for all regimes except for authoritarian countries.

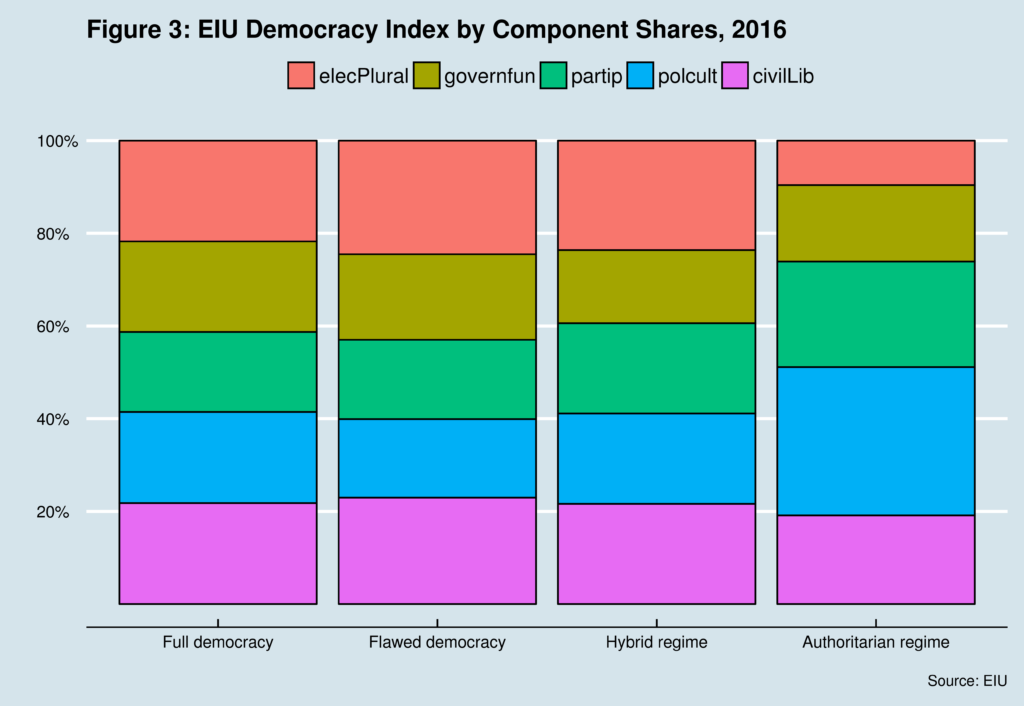

The relationship between index components for each regime type can be better seen in figure 3.

The US as “flawed” democracy

With all of the above in hand, answering the question about the democratic downgrading of the US in 2017 can be properly answered. In 2015, the US ranked 20th with an overall index score of 8.05, which is close to the threshold that separates full from flawed democracies. In this scenario, a small negative change in any of the five index components could push the country downwards towards a lower category. And that is exactly what happened. The functioning of government (governfun) component for the US was the only indicator that changed between 2015 and 2016. It went down from 7.5 to 7.14 thus lowering the overall index score to 7.98, a few millimeters away from the full democracy category.

Governfun is mostly an institutional component, but it also includes people’s perception of both government and political parties. It is indeed accurate to say that such perception has been declining in the US in recent years. But overall, this is a small change that has brought forward a change in regime categorization. On the other hand, such a change can be easily reversed, depending on what happens with the new US Administration.

Democracy Index and Human Development

In a previous post, I highlighted the potential relevance of UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) as an alternative or complementary measurement for overall human well-being. In short, the HDI adds health and education to the traditional GDP measurement – but does not include any governance or institutional components.

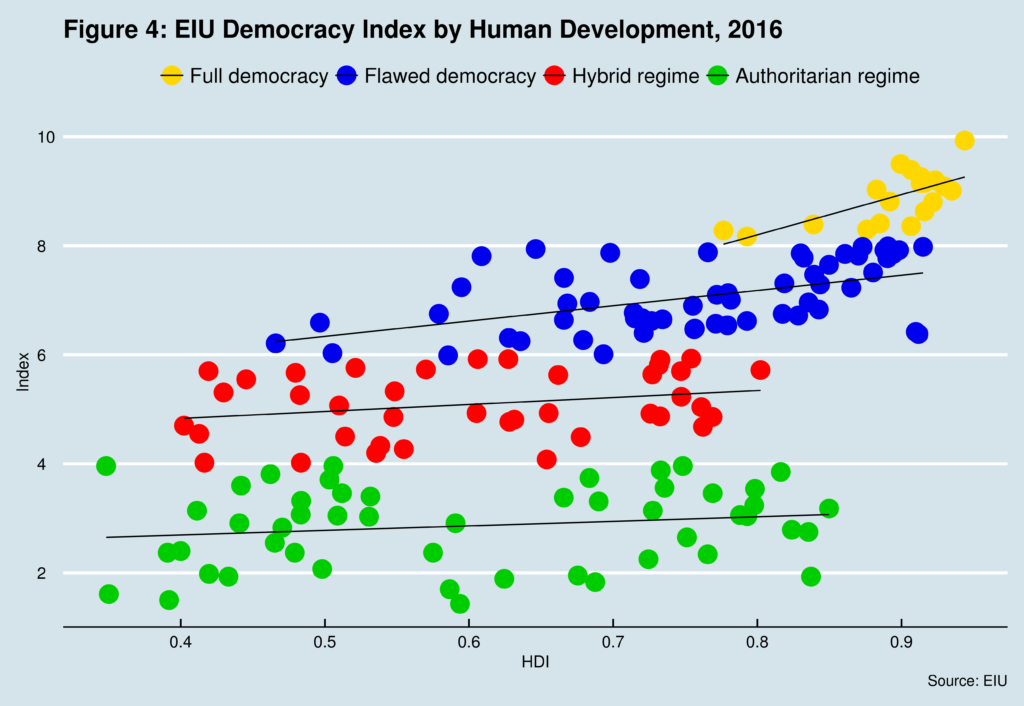

So it is perhaps a good idea to examine the relationship  between the HDI and the EIU democracy index. Figure 4 depicts such relationship.1 North Korea and Taiwan are not included here as HDI estimates for these two countries are not available. In addition, HDI data is from 2015 as the 2016 version will only be published in March of this year. The figure also includes a linear trend (or regression line) for each type of regime. The first thing to note is that as expected, all full democracies have high and very high levels of human development.2 2015 HDI scores above 0.8 are classified as very high by the Human Development Report. Scores between 0.7 and 0.8 are considered high. And countries with scores below 0.55 are in the low category range.

between the HDI and the EIU democracy index. Figure 4 depicts such relationship.1 North Korea and Taiwan are not included here as HDI estimates for these two countries are not available. In addition, HDI data is from 2015 as the 2016 version will only be published in March of this year. The figure also includes a linear trend (or regression line) for each type of regime. The first thing to note is that as expected, all full democracies have high and very high levels of human development.2 2015 HDI scores above 0.8 are classified as very high by the Human Development Report. Scores between 0.7 and 0.8 are considered high. And countries with scores below 0.55 are in the low category range.

A strong correlation between the human development and democracy exist for this group of countries. In effect, such correlation seems to decrease as we move from full democracies all the way down to authoritarian regimes. Looking at the trend lines for each of the other three regime types, the correlation decreases as the democracy index also decreases. For example, authoritarian regimes do have very high levels of human development while, at the same time, quite a few flawed democracies fall below high levels of human development. And a few are actually in the low HDI range.3 The correlation between HDI and full democracies is close to 0.7. If falls to 0.5 for flawed democracies and to 0.25 for hybrid regimes. For authoritarian countries is close to 0.18 which is certainly very low. Interestingly, correlations between the democracy index and the HDI by type or regime are consistently higher than those link to income measures such as GDP or GNI per capita.

Looking ahead

Certainly, none of these findings are really new. As a matter of fact, some of them have been discussed ad nauseam in the past.

Being that as it may, it seems clear that we still do not have an adequate measure of overall human well-being that encompasses relevant economic, social, political and cultural components.

Cheers, Raúl

Endnotes

| ⇧1 | North Korea and Taiwan are not included here as HDI estimates for these two countries are not available. In addition, HDI data is from 2015 as the 2016 version will only be published in March of this year. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | 2015 HDI scores above 0.8 are classified as very high by the Human Development Report. Scores between 0.7 and 0.8 are considered high. And countries with scores below 0.55 are in the low category range. |

| ⇧3 | The correlation between HDI and full democracies is close to 0.7. If falls to 0.5 for flawed democracies and to 0.25 for hybrid regimes. For authoritarian countries is close to 0.18 which is certainly very low. Interestingly, correlations between the democracy index and the HDI by type or regime are consistently higher than those link to income measures such as GDP or GNI per capita. |