By now, we are aware that data center deployments have a clear geographical bias. Indeed, one region is significantly ahead of the rest. Those comprised of mostly industrialized countries follow, albeit at a considerable distance. The rest can hardly breathe. In any case, such patterns could serve as the first clue about which areas are most attractive to the predicted deluge of new investments. In any case, let us delve a bit deeper.

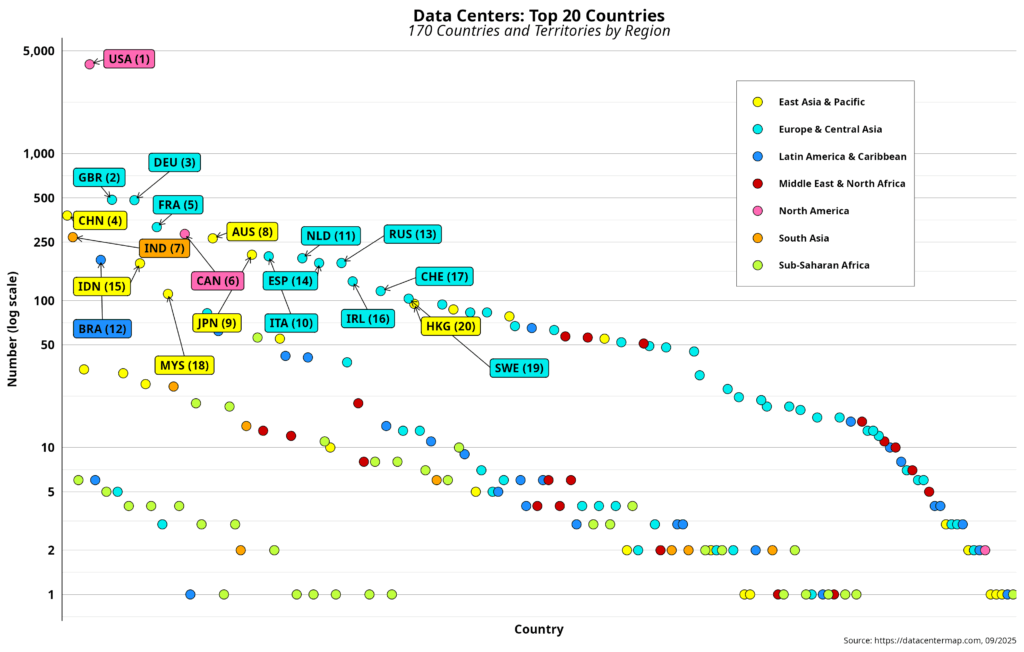

The figure below highlights the top twenty countries from the 170-nation sample, categorized by region (click image to enlarge).

All regions have at least one representative in the top group, except for sub-Saharan Africa. Europe takes the top spot with ten countries, followed by Asia and the Pacific with seven. Brazil, ranked 12th, is the only LAC country that makes the cut. The U.S. is the leader by a wide margin, with 4,050 centers, or 37.8 percent of the total. The UK and Germany follow with 4.5 percent, while China is fourth with 379 data centers, or 3.5 percent of the total. Moreover, only the first 17 countries have data center shares above 1 percent. In fact, the average share for the remaining 153 countries is 0.16 percent, thus flirting with zero.

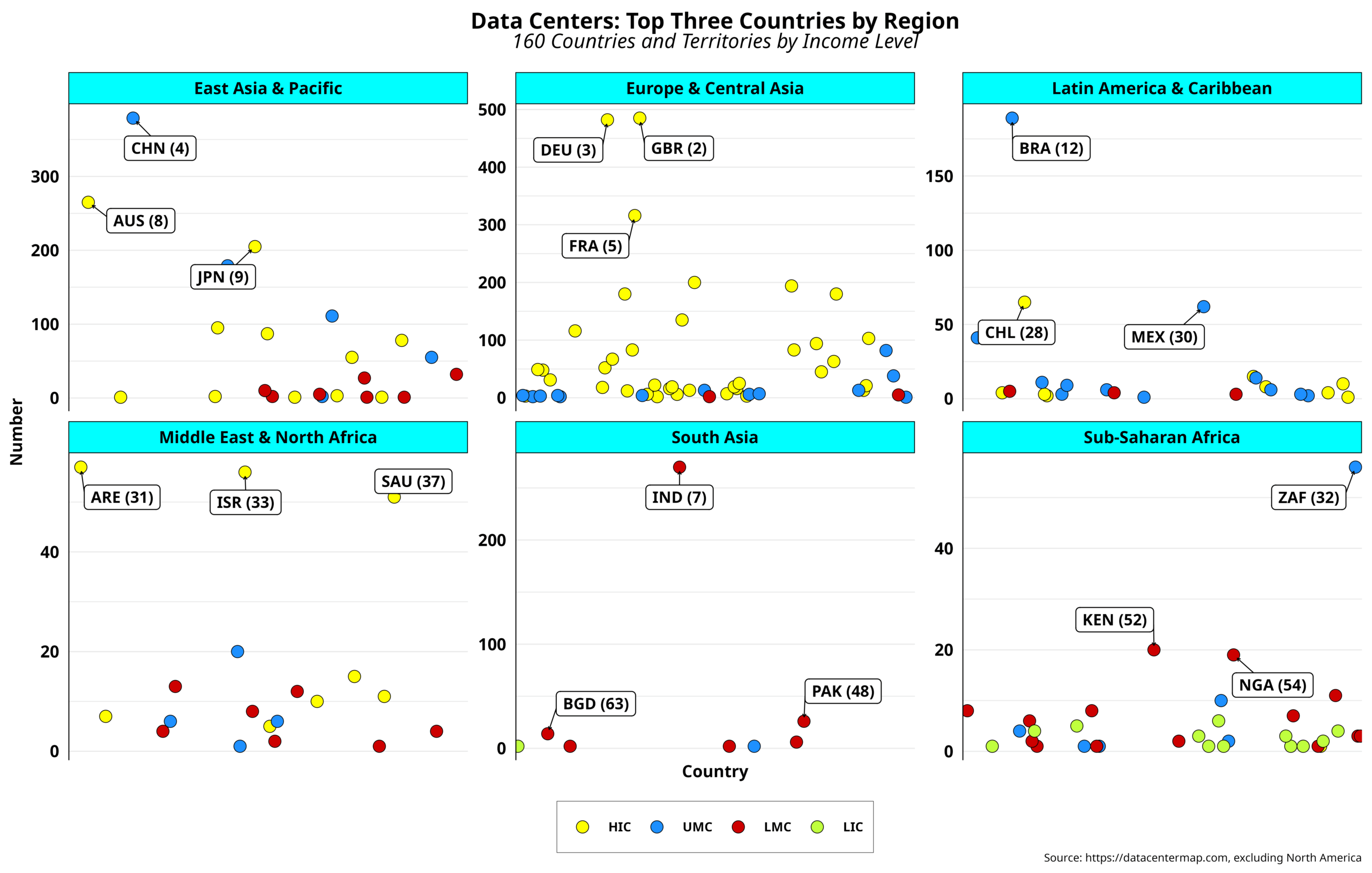

The following figure further illustrates the regional distribution of data centers, classified by income level according to the World Bank.

To minimize tight digital real estate, North America is excluded. We already know the U.S. is an outlier. Canada is part of the top ten club, while Bermuda hosts only two data centers. Note also that countries lacking World Bank income classification are excluded (seven in total, including Taiwan, with 34 data centers). For each of the other six regions, the top three countries are highlighted. The number in parentheses within the data label displays the country’s global ranking. Note that the y-scale for each region is unique to highlight intraregional differences. Interregional comparisons are thus not applicable in this case.

South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria are the top players in sub-Saharan Africa, with South Africa well ahead of the others. However, none of them is among the top 30 countries. Moreover, most countries in that region typically host fewer than 10 data centers. Saudi Arabia leads the MENA region, but its global ranking is lower than South Africa’s. Bangladesh is the lowest-ranked country among the 12 top regional leaders. In all areas where developing countries comprise the majority, regional leaders are significantly ahead of the rest, thereby revealing substantial intraregional gaps. Expect regional leaders to also attract new investments.

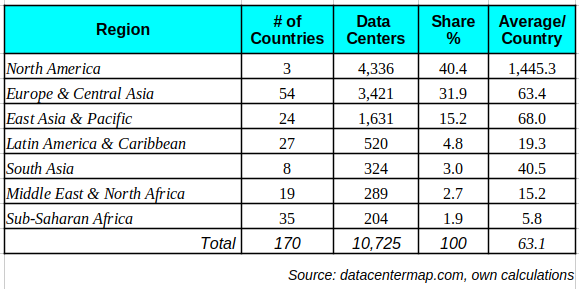

The table below provides summary statistics for all regions.

While the average per country might be spurious for North America, the rest pinpoint critical interregional differences. North America and Europe account for 72.3 percent of all data centers. The Europe rubric includes Central Asia. However, 94 percent of all data centers in the region (3,221) are located in high-income European countries. The contribution of Central Asian countries is thus minimal. Additionally, the combined share of LAC, MENA, and SSA is less than 10 percent of the total. Yet, all of them have a few regional leaders who could become investment magnets. The question is whether such investments will exacerbate intraregional differences or serve as an entry point for other countries to join the alleged wealth-generating party.

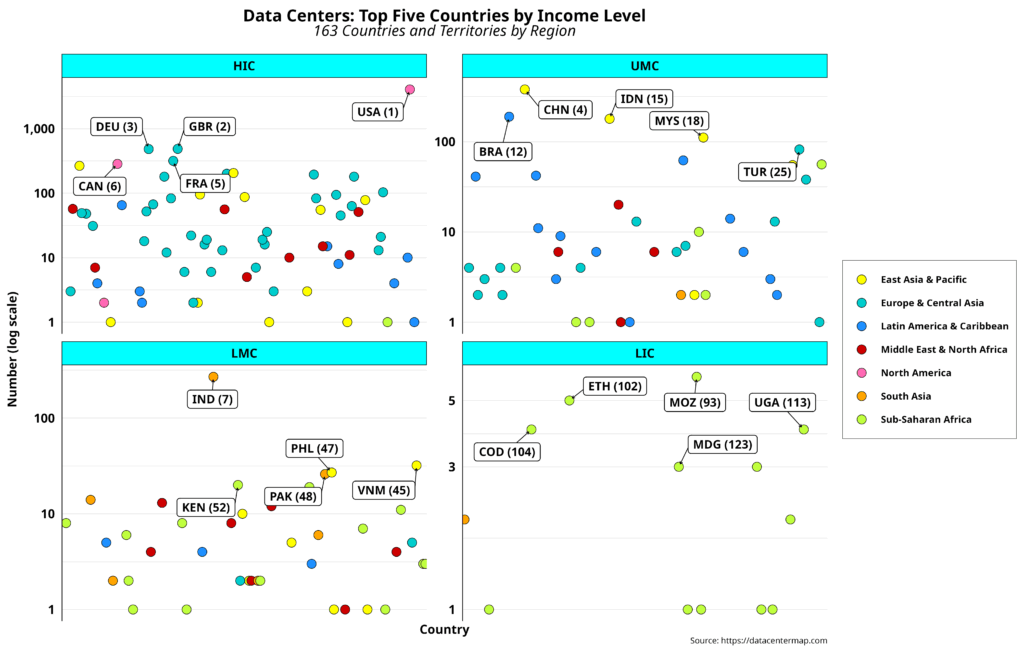

We can now change viewing lenses and focus on country income classification levels to uncover additional patterns. The figure below presents the top five countries, categorized by income level. Again, countries lacking such a classification are excluded. And y-scales vary by region.

Countries such as Turkey, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Pakistan appear in the top five of their respective income rankings for the first time. On the other hand, LICs are led by Mozambique, but none of the top five are ranked within the first 100 countries. Moreover, the number of data centers per LIC country is below seven. In numerical terms, HICs account for 81% of all data centers, while LMCs and LICs together account for less than 6 percent. Excluding LMC leaders, we should not expect the investment bonanza to reach all other countries in the bottom two income categories.

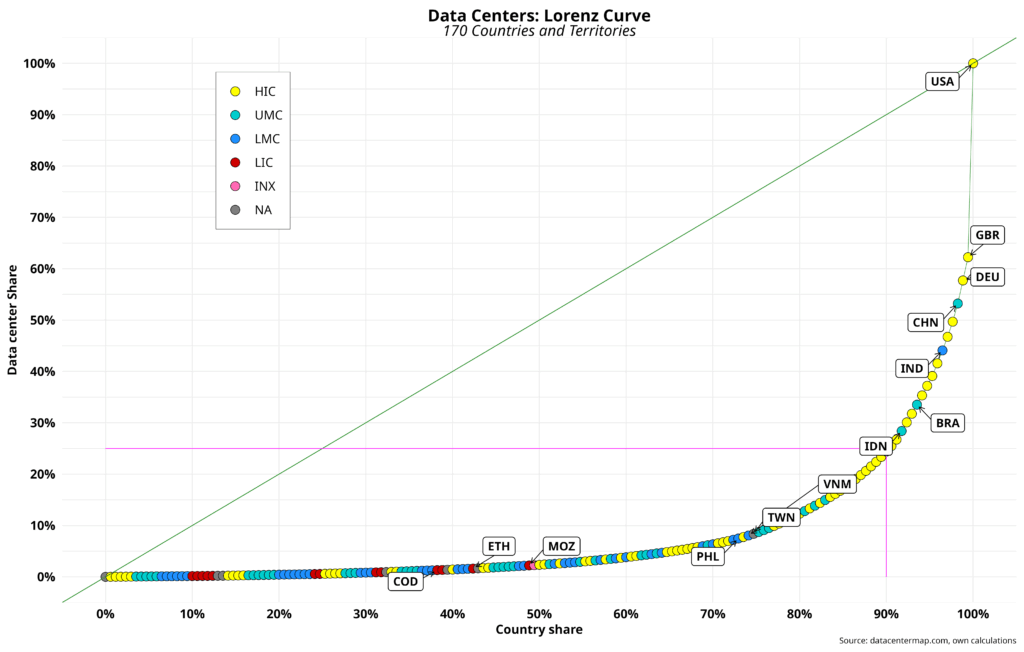

Undoubtedly, there is a strong correlation between a country’s income level and data center investments. This is also evident in the sharp inequality across countries, as depicted in the chart below.

It highlights the top three countries by income level, plus Taiwan, and includes all 170 nations. NA represents countries without income classifications, while INX is the WB code assigned to Venezuela. The top 10 percent of countries host 75 percent of all data centers. In turn, the bottom 60 percent cannot even reach 4 percent. Such numbers reveal inequality levels that easily beat the now-persistent income and wealth inequalities within and between countries.

We are now better equipped to answer the original question about the geography of the new data center boom investment. First, capital will initially move (and is already moving) to countries and regions where data center and cloud activities are already noisily thriving. That includes developing economies that are already part of the business cycle. But most investment will probably take place in high-income countries. Whether new investments in developing nations will magically trickle down to others remains to be seen. That seems doubtful, given that hyperscalers are migrating to AI data centers. These beasts could easily provide global cloud services. Smaller edge and modular data centers could then become significant players, as latency and access to local data may become priorities for maximizing profits.

From a competitive perspective, two issues must be emphasized. First, the role of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) needs to be examined. Big Tech and other large companies utilize M&A as part of their competitive arsenal to acquire or control firms that could eventually disrupt their seemingly endless cash flows, with regulators typically looking the other way. A 2025 report shows that data center M&A reached nearly 90 billion dollars in 2024. In March of this year, Google spent $32 billion to acquire a cybersecurity company specializing in cloud infrastructure. M&A deals are not limited to North America; they are also blazing in Europe and in Asia and the Pacific. All this activity confirms the primacy of the regions mentioned above. I have no idea if the available DCM data already takes this into account.

The second issue concerns the interplay between data centers and cloud providers, particularly hyperscalers. As LLMs usage grows almost exponentially, most people are now avoiding visiting follow-up or source websites. That has sparked serious discussions about whether AI could kill the web. In this light, cloud instances could become the preferred option, thereby attracting a significant portion of the expected data center investments. Not that data centers will necessarily die, by any means. Yet, their current mode of operation might change significantly. This trend relates to the edge and modular data centers mentioned earlier. By the way, these data centers are also more likely to utilize green technologies cost-effectively, and consequently have a reduced ecological footprint (in terms of water and land use) and environmental impact.

Lastly, the role that Global South countries should play at this juncture is also essential. Even though it should now be patently evident that some will benefit from the ongoing investment boom, most will be directly bypassed. That does not mean they need to sit at the fence permanently, patiently watching the ensuing transformation. On the contrary, they need to be decidedly proactive by seizing the AI opportunity. After all, data and local knowledge will eventually become direct targets as other markets saturate. AI policies and action plans, linked to industrial policies and sustainable development goals, should be in place to ensure the potential benefits of AI are disseminated inclusively. With this in hand, they could also seek alternative financial resources, ranging from public banks to regional businesses interested in a piece of the action, competing with the usual suspects.

Raul