[I wrote this edited draft case study for a larger blockchain research project led by The GovLab. The final project report included a shorter version of my draft.]

1. Overview

Launched in January 2017, the World Food Program Building Blocks blockchain initiative targets over one hundred thousand refugees living in the Azraq camp in Jordan. WFP beneficiaries receive cash-based transfers to purchase the essential goods needed for survival via authorized local stores. The project’s core focus is to increase the efficiency of the overall cash-based transfer scheme, ranging from refugee registration and processing to streamlining the required financial processes and reducing the number of local intermediaries. Blockchain technology has enhanced the entity’s core mandate by complementing and amplifying existing digital platforms. WFP has a solid track record of deploying digital technologies in these humanitarian contexts and is fully aware of the additional benefits blockchains can bring to bear. Blockchains, digital databases and biometrics together make up the trident WFP used to carve deep on-the-ground impact.

Key lessons learned

- Institutional capacity and structure play a key role in effective blockchain deployment.

- Project beneficiaries can indirectly benefit from blockchains without using or learning about new technology.

- Blockchain technology is an effective platform to increase efficiency, accompanied by crucial ID access and management improvements.

Distinguishing characteristics

- Effective deployment of blockchain technology as infrastructure in complex environments

- Subtle changes in the authentication of end users are possible without having to change end-user interfaces.

- Efficiency-led initiative yielding clear financial benefits, including cost-reduction and disintermediation, which can then be used for expanding programs

Problem definition and value proposition

Cash-based transfers to refugees have increasingly gained relevance within WFP’s on-the-ground modus operandi, replacing standard and high-cost direct food delivery to beneficiaries in most cases. While having clear advantages, cash-based transfers also introduced new challenges such as

- High financial transaction fees between WFP and local banks and vendors

- Increased financial risk including fraud, bankruptcy and corruption of local vendors

- Little to no beneficiary privacy as personal information is shared with banks

- High costs for adding new beneficiaries to the system

- Slow contracting arrangements between WFP and local entities

- Complex financial reconciliation of purchases and expenditures as multiple players are involved

- Heavy reliance on local vendor data and networks

- Lack of integration and interoperability between the various platforms deployed by other development agencies and partners.

The project’s core goal is to address most if not all of these issues by introducing blockchain as a back-end platform. Note that handling refugee ID processes and systems is not part of the project, at least not at this stage.

Key actors/Partners

WFP is the leading entity deploying blockchains via third parties as it has no internal expertise. WFP also makes all final project decisions.

Datarella initially furnished the blockchain infrastructure and core software development when required. Daratella has developed RAAY, a platform geared towards the 2 billion plus people lacking access to financial services. Datarella is no longer involved in the project.

Applied Blockchain, which specializes in DLTs and smart contracts, has assumed some of the responsibilities Datarella had at the beginning of the pilot.

Parity offers an Ethereum-based wallet that local partners and vendors use to access the blockchain platform.

IrisGuard supplies the biometrics platform to capture and manage iris scans.

WFP recently appointed Baltic Data Science, a Datarella subsidiary, to lead the scaling up of the Jordan project.

Identity life cycle focus

As a direct result of its efficiency-led approach, the project is centered on the administration and auditing/monitoring of cash-based transfers. The former entails the elimination of local financial intermediaries. That, in turn, increased the agency’s effectiveness in reporting and managing the overall delivery of cash-based transfers. While iris scans are now stored in a blockchain, no changes to authentication and authorization were introduced from the end user’s perspective.

2. Project Genesis and Description

Problem context and need

In 2015, the WFP innovation unit launched the Innovation Accelerator, which currently supports over thirty different projects worldwide. Building Blocks, established in 2016, is one such project. Its fundamental goal is to deploy blockchain technology to support the agency’s core mandate. Through Building Blocks, WFP is piloting a blockchain system in the Azraq Refugee camp in Jordan. The initial phase of the pilot targets over ten thousand refugees who receive cash transfers financed by WFP to purchase goods from authorized stores. The pilot streamlines the financial allocation and expenditure of cash transfers bypassing the local financial sector, reducing transaction fees and augmenting the transparency of the overall process. Building Blocks first completed a small pilot in Pakistan with one hundred people. It then used the experience to launch the larger pilot in Jordan in 2017.

Existing (legacy) system context

WFP has been using new ICTs for a while now. Before introducing blockchain technology, cash-based transfer schemes already used biometrics (iris scans), mobile money, and e-vouchers, among others. Cash-based transfers were initially introduced to 1. Allow beneficiaries to make their own choices; and 2. Foster the development of the local economy. However, cash transfers heavily rely on financial intermediaries such as banks, mobile money companies, carriers, and local agents. For each user, financial intermediaries have to 1. Create an account. 2. Have adequate distribution networks. 3. Authorize transactions and 4. Create financial and accounting reports. They also had to make the actual payments to authorized vendors.

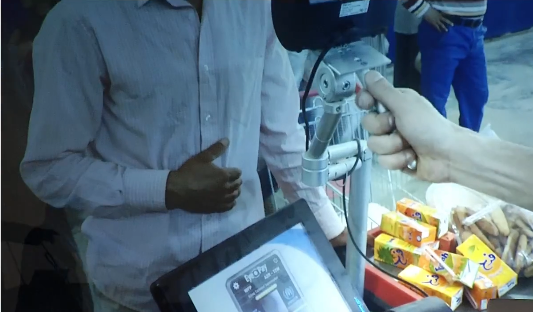

WFP provided intermediaries with a list of beneficiaries and supplied the total cash required to support food purchases. The bank then created all beneficiary accounts, informed them and agreed on a payment mechanism (cards, e-vouchers, etc.). The beneficiaries could then purchase their needed goods at an authorized local store. The local vendor identified the beneficiary via iris scans, checked the entitlement and made the final sale. The vendor then got payment from the respective intermediary.

Identity solution

Before the project was launched, refugees were authenticated and authorized via iris scans digitally stored in a relational database. The project changed the back end supporting iris scans but not the way users have to authenticate to get access to authorized entitlements.

Iris scans, not blockchain-based IDs, are still used to authenticate users. But now, while the beneficiary is identified in this fashion, authentication and entitlement checks happen via the blockchain platform, which is linked to a relational database where claims are verified. Transactions are recorded in the blockchain creating a record of refugee expenditures. Vendors in the network use a blockchain wallet to track transactions and get paid directly for their sales from WFP. Local banks are thus bypassed in the process as no new bank accounts need to be created locally.

In a nutshell, the project in Lebanon replaces the financial intermediaries with blockchain technology, thus reducing operational costs for WFP. Regarding ID, the only notable change is using blockchains in the back-end to authenticate and record financial transactions.

Blockchain technology use

The project uses a private permissioned (and modified) Ethereum-based blockchain platform, combined with traditional digital technologies and biometrics. The project uses Proof of Authority as a consensus algorithm, avoiding the hassles and inefficiencies of the standard Proof of Work consensus. The initiative is now starting to use tokens that are pegged to entitlements on a one-to-one basis.

User needs and interface design

End users (refugees) do not need to access any interface to get entitlements assigned to them by WFP. The end user thus remains oblivious to the back-end changes and has yet to see any direct benefit from using a blockchain-based infrastructure.

3. Institutional Approach

Governance, legal and regulatory context and constraints

WFP’s core mandate is to eliminate world hunger. Estimates show that over 800 million people in the world are hungry. WFP claims it supports over 80 million people. Its mandate also includes support in emergencies and crises like Syria and its millions of refugees with little to no food access. The delivery of its core mandate is partly executed via cash-based transfers to enable the poor to acquire the food supplies they need. WFP supports over 14 million people via cash-based transfers, roughly 15% of the total population supported by the UN agency.

Existing governance, legal and regulatory mechanisms already in place support project implementation. The key highlight here is that the pilot is fully aligned with the entity’s core mandate and addresses tangible barriers and challenges identified by staff on the ground.

Institutional partnerships, intermediation model

As is typical with state-of-the-art technology-related initiatives in the public sector, WFP has secured the services of external private companies specialized in blockchains and digital biometrics. However, WFP is still leading the project’s financial operations, which are a core part when cash-based transfers are part of the equation. Therefore, WFP also leads the overall implementation of the project.

Incentivizing use / Establishing institutional credibility

As a well-known UN agency, WFP has global institutional credibility, which helps open doors in most countries. Direct beneficiaries and partners have a lot to gain by being associated with the organization and being part of the old and new initiatives it promotes. In addition, the fact that the blockchain pilot is tightly aligned with the agency’s core mandate provides fertile ground for generating incentives to use its platforms.

Risks and mitigation strategy

Multiple UN agencies and other development organizations also support refugees. While WFP has a long-term goal of creating one single blockchain for all those in the sector, the reality of work on the ground might prevent this. Lack of UN agency coordination is a well-known issue for those working in or with the UN system. More than partners, UN agencies tend to compete as this might bring additional funding on board. A private permissioned blockchain being used in the project might not be conducive to enhancing coordination and cooperation.

4. Implementation and Scaling Strategy

Implementation

The project is focused on the administration and auditing components. That is consistent with the planned efficiency gains the project set from its inception. It translates into lower operational costs, heavy disintermediation and transparent reporting and monitoring mechanisms for cash-based transfers and overall financial operations. Project implementation follows standard processes and procedures well-established within the UN agency. External partners issue contracts that comply with UN rules and regulations regarding financial and administrative transparency. The development and successful deployment of the system took less than five months which is highly agile for these environments.

Scaling strategy

The initial pilot covers over 10,500 beneficiaries. By the end of 2017, it had made over 1.6 million US payments, accounting for over 200,000 transactions. According to a recent email from WFP, the project is bringing in savings of 40,000 USD per month or close to half a million per year. Such savings are, in principle, being shifted from operations to programs to either support more beneficiaries or increase cash allocations.

The project is now being scaled up and, as mentioned before, an external partner has been brought on board to support the process. Scaling up plans drawn last fall called for an expansion of the pilot to cover close to 100,000 refugees. This year the project is now protecting half a million refugees in the camps under WFP purview. Medium-term plans include efforts to increase collaboration with other UN agencies; one has confirmed plans to join. And in the long run, WFP is considering using the project as a stepping stone to the platform for providing foundational ID to refugees and other agency beneficiaries.

5. Intended Outcomes and Impact

Outcomes

The project’s key outcome is to strategically address the critical challenges of disbursing cash-based transfers to Syrian refugees in Jordan by deploying blockchain technology. Most of these challenges are efficiency related and include cost reduction, disintermediation (cut out the middle person) and administrative transparency (reporting, accounting, audits, and management). And the project is successfully delivering on the ground along these lines.

Impact

The project’s core impacts can be summarized as follows:

- The project can serve as a possible model for deploying and using blockchain technology in humanitarian and development contexts. Project beneficiaries face extreme local conditions where most basic services and facilities are not readily available, and thus using and deploying new technologies has higher risks. The initiative showcases both the power and limitations of blockchains in complex environments.

- In principle, the initiative could serve as an entry point that facilitates increased coordination and cooperation among UN agencies and other organizations working with refugees. That is possible given the distributed nature of the technology and its potential multistakeholder oversight.

- The project demonstrates that blockchains effectively reduce transactional and operational costs and facilitate disintermediation by eliminating third parties that added additional friction to the process.

- The initiative also showcases the potential of blockchain to foster financial and administrative transparency. That relates to reporting, financial management, and fiscal oversight of the resources being distributed to refugees.

6. Challenges and Potential Risks

While certainly delivering on the ground, the project still faces essential challenges, including

- Scalability. As the project aims to expand operations to cover a more significant number of refugees, scalability issues related to blockchains in general and Ethereum, in particular, will come to play. More so if the long-term goal is to host all refugee and related programs on one platform.

- Blockchain use. Refugees are not using the platform directly nor managing the identities created for them by WFP. While this has helped advance the project in its initial stage, it also shows the underutilization of the potential ID benefits of blockchain technology.

- Privacy. As a result of the above, the refugees’ privacy is still in the hands of a third party. Indeed, the project has decreased some privacy risks as it used to be in the hands of banks and financial intermediaries.

- Access and connectivity. Enhancing the use of blockchain by refugees will require that access to local networks and/or the Internet are in place.

- Design. Like most in the sector, WFP has taken a top-down approach in designing the project, thus excluding direct beneficiaries. This part explains some of the challenges mentioned above and the way iris scans are currently performed. Nevertheless, Building Blocks is planning to drop iris scans for future implementations.

- Local impact. Project disintermediation has increased efficiency. But on the other hand, it can harm the local financial sector and might lose one of its main clients. Jobs and economic growth might also be impacted. However, WFP says it is closely working with Central Banks.

7. Similar Initiatives

WFP refugee project is not the only kid on the block – but it is the only one delivering on a relatively large scale. Here are a few more.

- Bitnation refugee emergency response (BRER) is an initiative launched in 2015 to provide emergency services and humanitarian aid to refugees arriving in Europe. The project’s core goal is to provide a blockchain-based ID to refugees for authentication and validation. Unfortunately, data and information on the project is not readily available.

- Aid:Tech Lebanon pilot was a small-scale initiative also launched in 2015 that supported 100 Syrian families. The pilot raised 10,000 USD which were then distributed to the families via blockchain-based vouchers that could be redeemed at selected vendor locations.

- The Finland pilot targets refugees living in the country trying to access the local financial system. The government has partnered with a private company that issues pre-paid debit cards. Each card is, in turn, registered into a blockchain and thus has a unique ID with the required private keys. That facilitates access to financial services and bypasses banks and other financial institutions. This same scheme is now being used in other European countries and works more generally for those unbanked.

- Exsulcoin is one of the few blockchain startups working with refugees that has successfully completed an ICO. The platform goes beyond providing emergency services and humanitarian assistance to displaced populations. The platform targets the education of refugees and has developed an app that uses artificial intelligence to provide customized educational services to them. While very promising, the platform is not yet on the ground.

- Techfugees is a non-profit organization syncing up the tech community’s responses to the refugee crisis. It was five overarching goals, including infrastructure, identity and education. In addition, it has announced the Basefugees project, which will operate as a knowledge hub for innovators working in this space.

- Launched last December, the Rohingya Project’s aim is to provide identity and opportunity to Rohingya refugees. A pilot will start with one thousand refugees in Malaysia who will receive blockchain identity as well as means to gain access to the financial system. In addition, the goal is to have a complete census of Rohingya refugees. The project is still in its early stages.

8. Looking Forward

The WFP pilot shows the limitations of deploying a fully-fledged blockchain technology initiative in contexts where target populations live in conditions of dire poverty and systematic social inclusion. Assuming that such people can immediately use the technology is unrealistic. On the other hand, the pilot demonstrates that blockchain technology can be effectively deployed in such conditions by focusing on the supply side. Here, blockchain technology infrastructure capabilities are enshrined with efficiency leading the pack. Most of the direct benefits of the project fall on the donor and its core partners. While the privacy of refugees is one of the issues explicitly raised as a challenge in cash-based transfer schemes, the pilot does not entirely solve it. While minimal information about them is now shared with a reduced number of entities, refugees are still a few steps away from managing their own identities from who to how.

If other agencies launch or run independent blockchain technology pilots to assist refugees, the latter will need to create or have a new ID. The same goes for those who run refugee programs on alternative platforms supported by new technologies and biometrics. Agency coordination and interoperability thus become critical issues that can directly impact refugees and impose additional burdens on them. But agency coordination is not a technological issue that blockchains alone can solve.

In terms of design, the project takes a top-down, financial approach to tackle the supply side of the process. For the moment, little to no concern about the impact on beneficiaries is on the table, nor is an approach supporting co-creation processes where all parties involved in delivering the outputs envisaged are engaged. WFP is now exploring ways to change this approach.

Looking forward, the use of crypto-tokens by UN agencies, donors and development practitioners to finance their initiatives should be explored in more detail. In this context, crypto-tokens should function not as a store of value a la Bitcoin but as a standard of value or unit of account for all those involved in the project, thus immune to speculation and corruption.

9. References

Alexandre, A. (2018, April 21). Belgium Contributes To World Food Programme Blockchain Project. Cointelegraph. https://cointelegraph.com/news/belgium-contributes-to-world-food-programme-blockchain-project.

Asian Correspondent Staff. (2017, December 21). Blockchain technology employed to give Rohingya refugees identity cards. Asian Correspondent. https://asiancorrespondent.com/2017/12/blockchain-technology-employed-give-rohingya-refugees-identity-cards/.

Bajpai, P. (2017, November 17). How Blockchain Can Help Humanitarian Causes. Nasdaq. http://www.nasdaq.com/article/how-blockchain-can-help-humanitarian-causes-cm879186.

Cohen, H. (2017, August 18). Building Blocks: The future of cash disbursements at the World Food Programme. WFP. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtCBqDXE6Vk&list=PLQgu1-2q_ko_C3Pj90qLhxkXzkvtRJBh1&index=5.

Daniell, J. (2018, April 05). UN WFP Is Leveraging Blockchain Technology To Track School Lunches. Retrieved from https://www.ethnews.com/un-wfp-is-leveraging-blockchain-technology-to-track-school-lunches. B

Dupire, C. (2017, December 19). WFP Uses Blockchain Technology to Fight Hunger among Refugees. Jordan Times. www.jordantimes.com/news/local/wfp-uses-blockchain-technology-fight-hunger-among-refugees.

Gerard, D. (2017, November 30). The World Food Programme’s much-publicised “blockchain” has one participant. https://davidgerard.co.uk/blockchain/2017/11/26/the-world-food-programmes-much-publicised-blockchain-has-one-participant-i-e-its-a-database/.

Haddad, H. (2017, November 26). Blockchain for Humanitarian Assistance. WFP. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y50C2JEZMrQ.

Hebblethwaite, C. (2017, July 12). United Nations WFP extends Syrian refugee Blockchain scheme. https://www.blockchaintechnology-news.com/2017/06/14/wfp-extends-syrian-refugee-blockchain-scheme/.

Hounsell, B. (2017, March 14). Refugee Digital Divide: Innovation for Africa’s Displaced Falls Behind. https://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees/community/2017/02/22/refugee-digital-divide-innovation-for-africas-displaced-falls-behind.

International Development Forum. (2018, March 16). Blockchain could transform identification and aid processes for refugees. http://www.aidforum.org/Topics/disaster-relief/blockchain-could-transform-identification-processes-for-refugees.

Juskalian, Russ. (2018, April 12). Inside the Jordan Refugee Camp That Runs on Blockchain. MIT Technology Review. www.technologyreview.com/s/610806/inside-the-jordan-refugee-camp-that-runs-on-blockchain/.

Kenna, S. (2017, November 28). How Blockchain Technology Is Helping Syrian Refugees. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2017/11/05/how-blockchain-technology-is-helping-syrian-refugees_a_23267543/.

Lace, E. (2015, September 18). Bitnation Registers First Refugees on the Blockchain. Coin Telegraph. https://cointelegraph.com/news/bitnation-registers-first-refugees-on-the-blockchain.

Lucsok, P. (2018, March 20). Fighting hunger with blockchain. Parity Technologies. http://paritytech.io/fighting-hunger-with-blockchain/.

Makadiya, P. (2018, March 23). WFP’s Ethereum Project Successfully Serves 100,000 Refugees, Now Aims Even Further. https://btcmanager.com/wfps-ethereum-project-successfully-serves-100000-refugees-now-aims-even-further/.

Opp, R. I. (2017, September 30). Can Blockchain end hunger?’. WFP. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5iK5h6BOpNo&t=1120s.

Orcutt, M. (2017, September 05). In Finland, digital currency is helping refugees start participating in society faster. Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/608764/how-blockchain-is-kickstarting-the-financial-lives-of-refugees/.

Parker, L. (2016, October 03). AID:Tech offers blockchain solutions to help United Nations and European Commission with refugee problems. Brave New Coin. https://bravenewcoin.com/news/aidtech-offers-blockchain-solutions-to-help-united-nations-and-european-commission-with-refugee-problems/.

Reuter, V. M. (2017, May 22). Building Blocks – How the World Food Programme is harnessing Blockchain technology to deliver humanitarian assistance. http://datarella.com/building-blocks-how-the-world-food-programme-harnesses-blockchain-technology-ro-deliver-aid/.

Simonsen, S. (2017, December 21). 5 Reasons the UN Is Jumping on the Blockchain Bandwagon. Singularity Hub. https://singularityhub.com/2017/09/03/the-united-nations-and-the-ethereum-blockchain.

Snowden, B. (2017, November 27). Coding and tech skills help refugees and low-income communities to succeed. Phys. https://phys.org/news/2017-11-coding-tech-skills-refugees-low-income.html.

Ward, T. (2017, June 14). A New Trial Proves that BlockChain Could Help Us Feed the World. Futurism. https://futurism.com/a-new-trial-proves-that-blockchain-could-help-us-feed-the-world/.

WEF. (2018). The State of Cash in Humanitarian Aid. Davos 2018. https://www.facebook.com/accenturecommunity/videos/1635117423215504/.

WFP. (2016, October 06). WFP Introduces Iris Scan Technology To Provide Food Assistance To Syrian Refugees In Zaatari. WFP. https://www.wfp.org/news/news-release/wfp-introduces-innovative-iris-scan-technology-provide-food-assistance-syrian-refu.

WFP. (2017, May 30). Blockchain Against Hunger: Harnessing Technology In Support Of Syrian Refugees. https://www.wfp.org/news/news-release/blockchain-against-hunger-harnessing-technology-support-syrian-refugees.

WFP Innovation. (2107, June 01). Blockchain Against Hunger: Harnessing Technology In Support Of Syrian Refugees. http://innovation.wfp.org/blog/blockchain-against-hunger-harnessing-technology-support-syrian-refugees.

Wong, J. I. (2017, November 03). The UN is using ethereum’s technology to fund food for thousands of refugees. Quartz. https://qz.com/1118743/world-food-programmes-ethereum-based-blockchain-for-syrian-refugees-in-jordan/.