As mentioned in the previous post, capital investments in data centers are expected to hit record sums. Predictions for 2030 suggest that nearly 7 trillion dollars will be heading that way, with 25 percent of that amount allocated to energy resources alone. Indeed, Big Tech is not expected to be the only player in this lucrative game, but will undoubtedly have a decisive magnet role, attracting other voracious capitals into the fray. So where exactly is this financial miracle going to take place?

Data centers have been around for several decades. Many probably heard about them for the first time when the word “cloud” entered our daily vocabulary. While real clouds are comprised of water drops and ice crystals, the Internet cloud is somewhat of a misnomer, as it suggests something intangible—something we cannot really grasp with our hands, much like the clouds in the sky. It thus hides the very tangible, real requirements that any data center incessantly consumes to perform its vital, irreplaceable functions. This includes ample water and energy resources, as well as a wide range of hardware, software, network access, and connectivity. Regardless, data centers already have a history, which is only now being revealed in detail. So what is the geography of such handy centers? We need data to answer such a question.

Research I conducted over three years ago uncovered CloudScene as a reliable data source. I downloaded the publicly available data into a spreadsheet. Accordingly, by September 2022, there were 6,334 data centers, with the U.S. accounting for 43 percent of the total. Germany was second with 8 percent, while the UK came in third with 7 percent. While no African country made the list, Brazil and Mexico accounted for just over 2 percent of the total. However, note that only 15 countries were included in the sample data. Additionally, the distinction between data centers and cloud infrastructure was not consistently highlighted.

At this point, it is probably a good idea to reintroduce the various types of data centers available. A concise definition and thorough explanation of its architecture are provided here. Five data center types are usually acknowledged: 1. Colocation. 2. Enterprise. 3. Managed Services. 4. Cloud. 5. Edge. Hyperscalers are part of the cloud team, albeit operating on a much larger scale. The ongoing AI revolution is transforming the dynamics of data centers. In this light, some argue that a new type of data center has emerged: the AI data center, which exclusively runs LLMs and related systems and caters to the exponentially growing demand. Nevertheless, I could argue that the AI data center is yet another form of cloud infrastructure, now specialized in a single, widely used technology. In any case, what is perhaps more relevant here is that cloud data centers have unique business models that clearly distinguish them from the other four types.

Today, CloudScene site hosts a data center leaderboard that displays the top 10 data center operators by region, provided users create an account and log in. It also offers country information by region. In that world, Equinix emerges as the indisputable leader across most areas. Yet, the company works in close partnership with the so-called hyperscalers, such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, which together control 63 percent of the cloud market. According to this source, there are over 12,000 data centers globally, with the U.S. leading with 5,426, followed by Germany and the UK, each with just over 520 locations. We can conclude that, over the past three years, the number of data centers and cloud providers has doubled, with the U.S. consistently leading the competition.

datacentermap.com (DCM) provides more detailed information at the country level, covering all continents and regions. DCM features separate global maps for data centers and cloud providers, enabling drill-downs by country, state, and city (or market, as they are referred to), with comprehensive insights on operators at the local level. While most of the data can be displayed on the website, data exports are available for purchase only. The data is primarily sourced directly from data centers and cloud operators, who also utilize the site for marketing purposes. DCM complements this with in-house research, as well as contributions from end users who can pinpoint errors or missing information. The company acknowledges that the data has gaps. It also suggests mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are the prime reason for data mutations and inaccuracies. The site also offers data on IXPs (Internet Exchange Points) that is not as comprehensive as that provided by Telegeography.

DCM data covers 170 countries and territories. As of this writing, it accounts for 10,725 data centers and 832 cloud service offerings. It covers over 350 cloud providers, but does not explicitly mention the number of data center operators in action. For a list and description of the top 250 cloud and data center providers, go here. All this suggests that competition in the sector remains intense, despite the cloud market being dominated by three Big Tech companies.

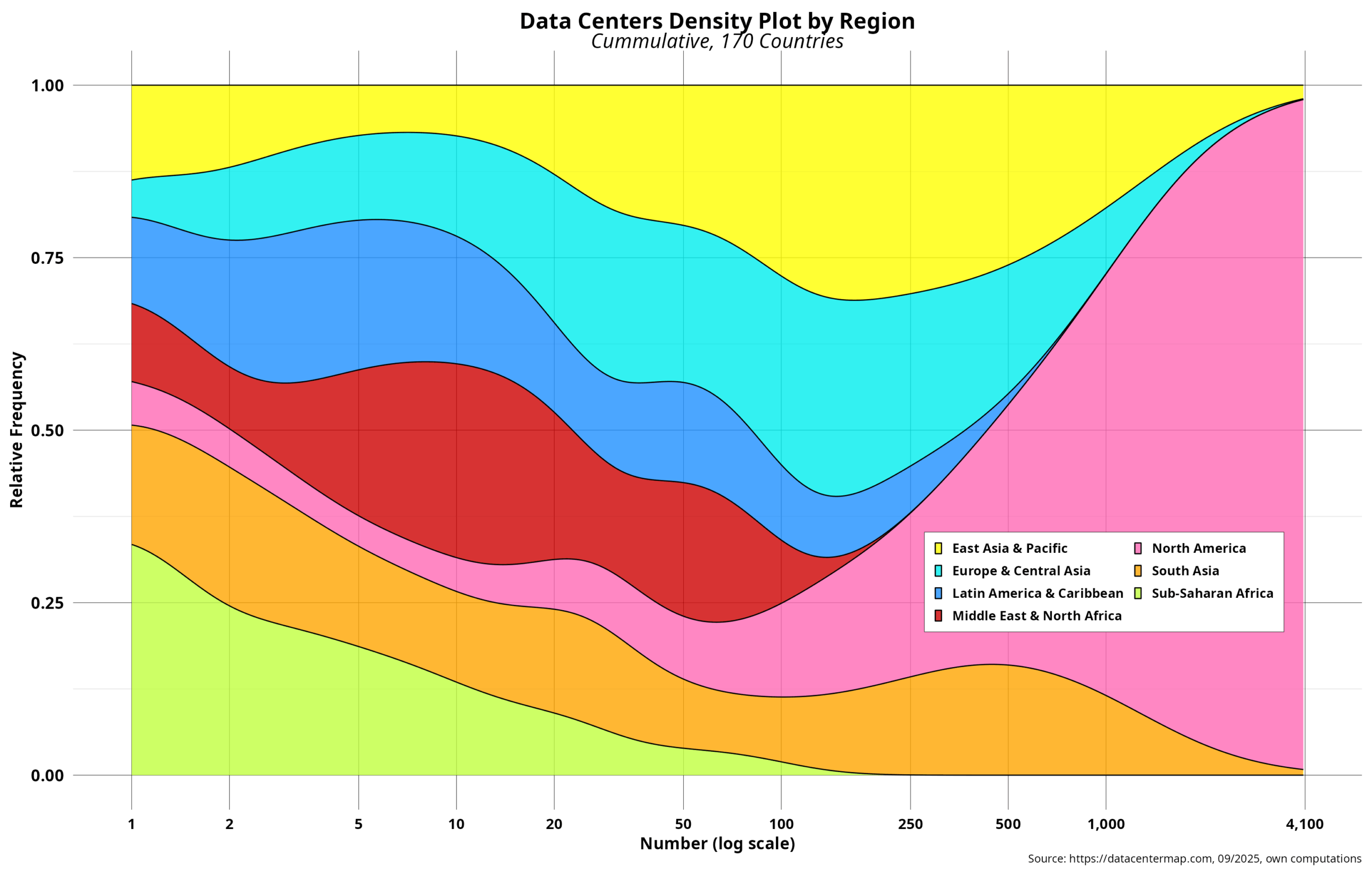

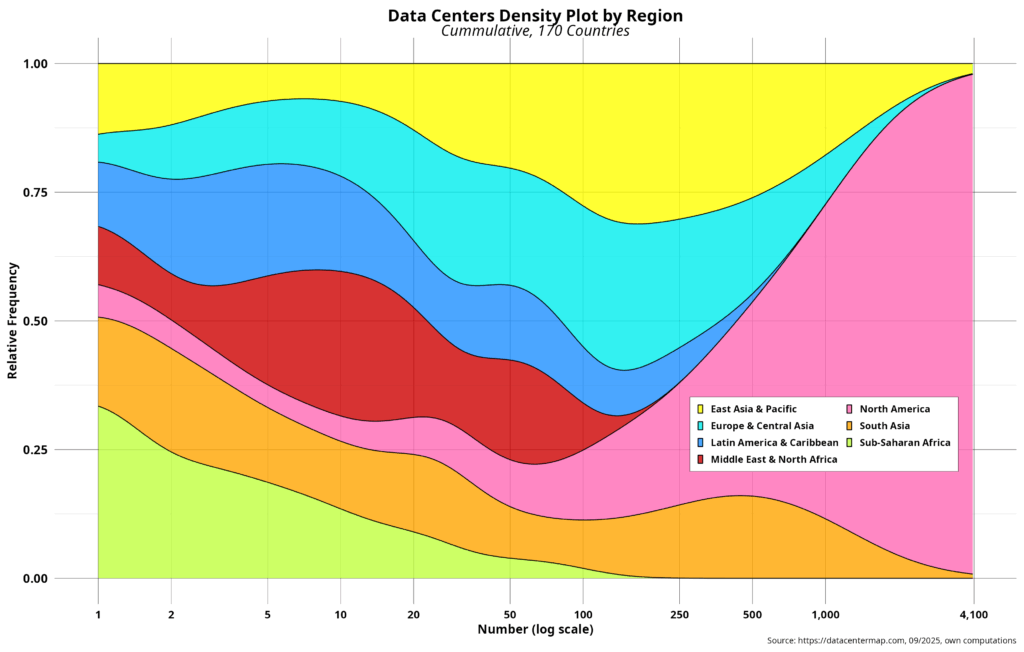

Let us start by examining the geography of data centers and quickly review their regional distribution by DCM, as depicted in the graph below.

The distribution of data centers across regions varies significantly, with sub-Saharan Africa at one extreme and North America, spearheaded by the U.S., at the other, where deployments reach their maximum level. Europe and Central Asia and East Asia and the Pacific follow North America and seem to be competing for the second spot, with the former ahead, for now. East Asia beats LAC and MENA, but the differences among them are not as dramatic.

In the next post, I will explore such uneven development more closely.

Raul