Have you ever bought something from Google? Many will likely answer positively—perhaps a tablet or a phone, or possibly a subscription to YouTube or Google One. Back in the early 2000s, most would have responded negatively, though. At the time, the company was synonymous with robust and mostly accurate web searches, and no one was even considering buying anything from them, as the service was free (i.e., no cost to end users) — and still is today.

In 2002, Google introduced the Search Appliance, a dedicated server designed for rack-mounted installation in corporate server rooms. To the best of my knowledge, that was Google’s first venture into the hardware business. The unit provided document indexing capabilities using Google search technologies. However, both hardware and the operating system were furnished by third parties. In August 2004, I contacted the company to inquire about the appliance and potential deployment for internal UNDP use. I was promptly offered a server with limited capabilities to test it before making a final purchasing decision. The server arrived in early September. The shipping box was relatively small but rather heavy, containing a bright yellow server resembling a hi-fi power amplifier with no front controls.

The next step was to install the machine in the corporate server room. I had the blessing of top management and obtained the agreement of the corporate IT division to add the device to the corporate network, provided I did it on my own. No problem, no sweat, I retorted. The installation was relatively simple. I probably spent more time finding the right corporate rack to mount the server. Once the server was running, the fun commenced. Indexing took several hours, and by the end of that week, it had already indexed over 20,000 documents. A week or so later, I did a demo for senior managers, who were impressed. The recommendation was to proceed with purchasing the miracle search machine. Note that Google was licensing its search algorithm, not selling it. Prices varied according to the number of documents the client wanted to crawl. Those aiming for 1 million documents would have to disburse $125,000 for a 2-year contract. We ended up licensing the unit for 50,000 documents at a discounted price of 40k for two years (or 67k, at 2024 prices).

Procurement processes at UNDP had stringent requirements and regulations, requiring a substantial amount of paperwork. The requirements included obtaining at least three bids from companies with a minimum of five years of expertise, as well as matching annual reports and audit records. Google, of course, did not qualify since it did not have any of the five-year requirements. Moreover, the market for web search appliances was nonexistent, so getting three bids was almost impossible. For the procurement committee, Google was a startup specializing in web searchers. It had no record whatsoever of making any sort of hardware! They were right on all counts and rejected the procurement proposal. I then had to make a case for a waiver from competitive bidding, which, after some back-and-forth, was approved. The appliance survived for over a decade and was decommissioned once UNDP moved its server room to the cloud. I was asked to remove the appliance from the soon-to-be-dead server room and ship it back to Google. Google stopped supporting the server around the same time, as the company had already entered the cloud business and was not eager to compete with itself, given the already intense competition with other cloud providers.

We can now rephrase our original question: How does Google generate revenue? Obviously, it needs to sell stuff to a wide variety of clients. However, its signature product, web searches, can be used gratis. If we consider Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon, they must sell their signature products (iPhone/Mac, Windows/Office, and online retail trade, respectively) to amass profits. There is no way I could use any of these products for free, at least legally. On the other hand, Meta/Facebook is more in Google’s camp: I can use most digital services for free if I create an account and reveal my identity. Fake accounts exist, but the company does its best to delete them. In 2024, over 2 billion such accounts were removed, for example.

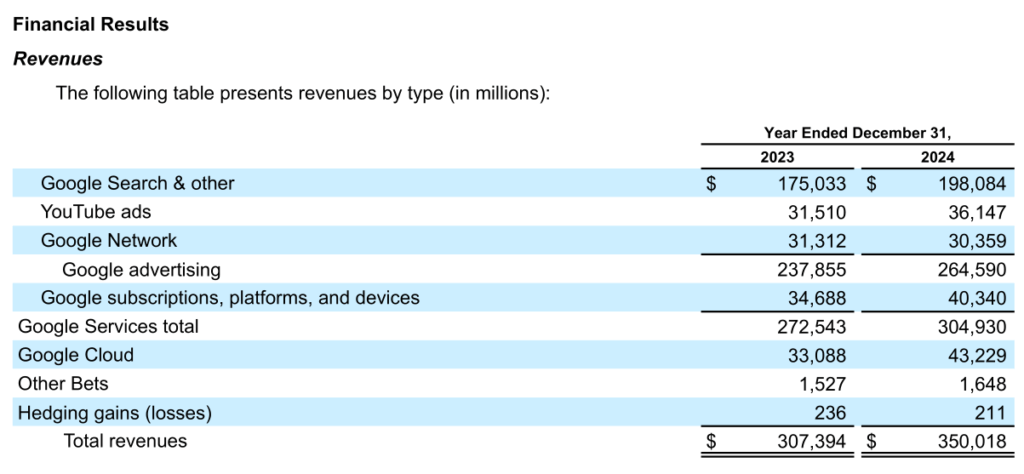

The table below, taken from Google’s SEC report submitted in February of this year, details the company’s revenues (now called Alphabet) for 2023 and 2024.

Last year, advertising accounted for 75.6 percent of all revenues, with Google Cloud a distant second at 12 percent. Revenues grew by 13.9 percent, spearheaded by cloud services that increased by almost 31 percent, likely driven by investments in GenAI-related infrastructure. Subscriptions, platforms, and devices grew 16.3 percent, outpacing Google advertising by 5 percentage points. The SEC report shows that 51 percent of all revenues came from non-US clients (tariffs, anyone?). The company also spent 14 percent of its revenues (approximately $ 50 billion) on R&D and reported 183,000 employees by the end of 2024. It also invested $ 52 billion in land and equipment, and nearly $ 3 billion in acquisitions (buying other companies).

In 2004, when I was trying to get my hands on the power amplifier/search appliance, the company had a different profile. It had 3,021 employees, and ninety-nine percent of all revenues (close to 3.2 billion or 5.3 billion in 2024 USD) came from advertising, with licensing struggling to reach one percent. YouTube did not exist yet, and the cloud was still in diapers. At the time, Google was still a two-sided digital platform focused on the then-emerging web search market. Advertisement was the only way to make profits, as the company’s 2004 SEC report says:

“Google is a global technology leader focused on improving the ways people connect with information. Our innovations in web search and advertising have made our web site a top Internet destination and our brand one of the most recognized in the world… We generate revenue by delivering relevant, cost-effective online advertising. Businesses use our AdWords program to promote their products and services with targeted advertising. In addition, the thousands of third-party web sites that comprise our Google Network use our Google AdSense program to deliver relevant ads that generate revenue and enhance the user experience… We place a premium on products that matter to many people and have the potential to improve their lives, especially in areas in which our expertise enables us to excel. Search is one such area… Communication is another such area… Gmail, our new email service (available in a limited test), offers a gigabyte of free storage for each user, along with email search capabilities and relevant advertising. Delivering an improved user experience in Gmail has similar computing and software requirements as our search service.” (my emphasis)

What I find most fascinating about the quote is how innovation was not limited to web search but also encompassed advertising. Advertising innovation was needed to allow businesses and others to place ads on a digital platform that was totally unfamiliar to them at the time. So Google developed advertising-placement algorithms to complement its core technologies and generate revenues. However, AdWords and AdSense do not rely on patents but on trademarks. Therefore, the core bet was on the volume of users, not royalties or licensing. The more eyeballs it could offer to advertisers, the higher the potential revenues and total net income. The classic media advertisement model has been revisited and upgraded, now thriving in the digital world.

Of course, Google is not a traditional media company. It does not produce direct content, such as a newspaper or a broadcasting company. As an early digital two-sided market, it sits between advertisers and potential consumers. It is thus a network intermediary that disintermediates analog processes and centralizes them within its exclusive digital domain. Once that happens, it can create new digital intermediaries supported by the digital advertising model while sharing revenues with them. “Thousands of third-party web sites” thus work in tandem with the company to increase the number of eyeballs looking at digital screens and maximize revenues. If you cannot beat them, join them!

Quantitative and qualitative differences are also at work. On the former, Google offered a single platform to advertisers where millions of users worldwide could be reached instantly and cost-effectively. Any business attempting to do so the “old-fashioned way” would have had to spend millions, a risky operation, especially in small or unknown markets where costs could easily outweigh revenues. Qualitatively, the company could offer customer profiles developed based on email or web searches to advertisers, who could then target specific population segments where their products and services could be more relevant than otherwise. While web search remained free and did not require authentication, Gmail did, thus permitting more nuanced profile development on a person-by-person basis. That is the model that, a few years later, Facebook completely mastered!

To achieve this, Google had to heavily invest in digital infrastructure and develop new applications to manage the data tsunami. That was already clear to the firm back in 2004:

“Our business relies on our software and hardware infrastructure, which provides substantial computing resources at low cost. We currently use a combination of off-the-shelf and custom software running on clusters of commodity computers…It simplifies the storage and processing of large amounts of data, eases the deployment and operation of large-scale global products and services and automates much of the administration of large-scale clusters of computers.

Although most of this infrastructure is not directly visible to our users, we believe it is important for providing a high-quality user experience. It enables significant improvements in the relevance of our search and advertising results by allowing us to apply superior search and retrieval algorithms that are computationally intensive. We believe the infrastructure also shortens our product development cycle and allows us to pursue innovation more cost effectively.

We constantly evaluate new hardware alternatives and software techniques to help further reduce our computational costs. This allows us to improve our existing products and services and to more easily develop, deploy and operate new global products and services.”

Indeed, Google was already in the big data business way before the term became a staple in digital circles. It created the Google File System and refined MapReduce (PDF) for that purpose. Such efforts led to the development of Hadoop, an Open Source framework for distributed computing that handles vast amounts of data.

In 2006, Google acquired YouTube, and five years later, it entered the cloud market, following the stunning success of AWS, which had been launched in 2006, coincidentally. We can conclude that Google has been a multi-sided digital platform since. And yet, its primary source of revenue remains advertising.

Raul