A recent blog tackles the issues surrounding Africa’s digital sovereignty. It first defines sovereignty as a country’s capacity to independently create, develop, and govern AI. However, the supreme adjective I previously highlighted is missing from this definition. At any rate, the authors rightly emphasize that sovereignty comprises technical and political issues. On the technical side, the post is curiously fixated on China and its infrastructure investments on the continent. Paradoxically, Big Tech is not even mentioned once, as if they were missing in action. They are not. Very odd, indeed. One could also argue that digital infrastructure investments benefit big platforms directly and indirectly, as potential customers could increase exponentially at no cost!

The political dimension is a bit more complex. Last year, the AU published the Continental AI Strategy. However, many countries’ immediate challenge in embracing it stems from a lack of local institutional capacities to move forward and implement comprehensive AI regulations. The end result of this will be “regulatory fragmentation” that can be exploited by external actors, thus jeopardizing AI governance, sovereignty, and safety. The post argues that such a gloomy predicament can only be overcome by embracing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) framework and the recently endorsed Digital Trade Protocol (DTP; PDF here).

DTP has 11 sections comprising 52 articles. Data governance has its section (Part IV) covering cross-border data flows, personal data protection, computing facility location, and data innovation. However, the blog places all its bets on cross-border data flows, arguing that embracing the free flow of data will trigger substantial GDP growth and job creation while reinforcing regional integration. However, the DTP text is a bit fuzzy regarding actual implementation. First, it refers to an annex on cross-border data flows, which is not part of the official document. Furthermore, it allows “State Parties” to erect their own data regimes, provided they submit legitimate policy reasons. Therefore, I am not convinced free cross-border data flows will be that free, nor would they trigger the virtuous economic cycle anticipated by the blog.

In any case, the text seems to reflect that not all AU countries share the same perspective on data flows. It goes without saying that similar language is also found in the article on computing facilities, a synonym for data centers. Here, we encounter once again the friction between internal and external sovereignty.

Comparatively, the AfCFTA DTP is a state-of-the-art piece of policymaking that covers all areas highlighted in other agreements, such as USMCA and RCEP. However, the former has a much larger number of countries to contend with. In addition, no regional or global hegemon is directly involved. While economic diversity in continental Africa is prevalent, over 40 nations are classified as low-income or lower-middle-income by the World Bank. In fact, no country in the continental area is part of the high-income rubric. That clearly shows that the socioeconomic playing field is more levelled. In that light, regional agreements are more relevant and should be flexible, allowing countries to carve their own development path if needed. DTP is indeed doing this de facto.

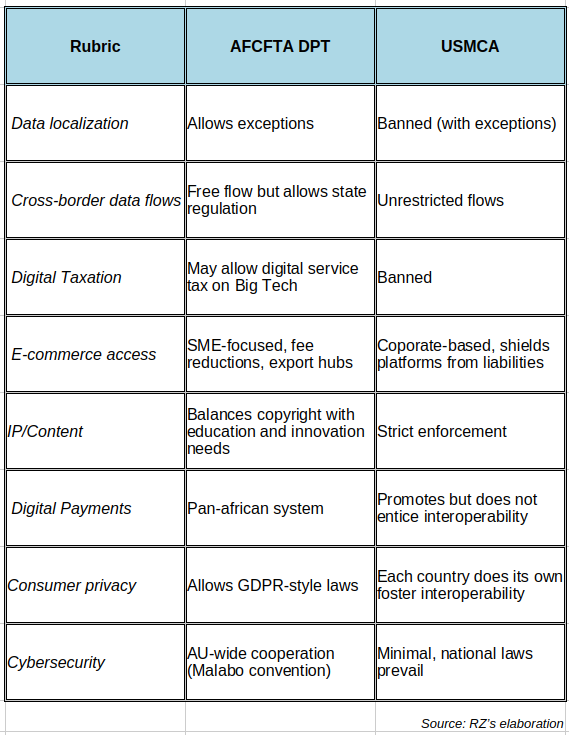

The table below compares key digital trade rubrics between AfCFTA and the USMCA.

The differences between the two are pretty sharp. We can conclude that DTP strongly focuses on fostering human development, thus responding to the continent’s core priorities. Recall that when AfCFTA was first completed, it was closely aligned with the UN SDGs. A more level socioeconomic playing field provides fertile ground for such developments.

Regarding digital sovereignty, perhaps it is time to revisit Andrée Blouin’s book My Country, Africa, which calls for the continent to always think and act as one. In the documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’état, we can also see her in action. She certainly practiced what she preached, consistently, even risking her life.

So maybe continental digital sovereignty is part of the answer vis-à-vis global hegemons and the always-growing and voracious Big Tech. Of course, the EU is doing something similar, albeit for very different reasons. Do not copy them, then.

Raul