The rainy season had already begun, but, as usual, it did not provide any relief from that sweltering heat that never abandoned the small rural town. It was a regular Thursday morning, and Cesar planned to head back to the farm riding his mule, always carrying his shotgun. One never knows what might happen along the way. The previous evening, someone kept playing the same love song over and over, disrupting the sleep of many villagers. Even so, he had dreamt of elephants after watching a film the previous Sunday. And while he was putting his boots on, he could hear Pastor’s clarinet, who lived close by. He asked his wife about his spurs. All set, he loudly left the house. It was raining, of course, but nothing could stop him. Or so he thought. Once on the mule, he saw it plastered to the house’s main door. He quickly read its contents in blue ink, slightly slushed by the rain, with what seemed to be intentional typos, as if a child had written it. Full of rage, he tore it apart and started to leave town. Suddenly, he changed his mind, heading back to Pastor’s house. And then shot him to death, the whole town shaken by the thundering noise.

The town’s Mayor, who also headed the local police and had absolute control over almost everything else, was about to sleep when he heard the shot. He immediately got into action. He knew Cesar well and subdued him without having to fire his pistol. Just like many others, Cesar had been pasquinaded. But, unlike the rest, he had taken matters into his own hands. However, Pastor was not his wife’s lover, contrary to what the anonymous public posting denounced. Most in town knew he had a girlfriend and planned to marry her within months.

In such a small town, rumors and gossip abounded, but most did not take them seriously. Indeed, they had become the town’s self-made music, always playing privately but never heard publicly. In fact, villagers were unafraid of the pasquinades’ content but lost plenty of sleep, thinking they could get one delivered overnight. The ultrapowerful mayor, however, had a very different take on the subject. Those responsible for placing pasquinades all over town were part of a conspiracy to topple the government. They will eventually join the resurgent guerrillas, he concluded. They had to be stopped by any means. In his eyes, disinformation was subversive. He had no choice but to declare a state of exception and deploy police all over town. Pasquinades also overshadowed the government’s own (dis)information campaigns routinely disseminated by radio, the few newspapers that arrived from the large urban centers, post mail and the interactive yet slow telegraph office the mayor had under very tight control.

García Márquez’s In Evil Hour, written in the early 1960s, is the source of this story. No Internet was available then, and television had yet to reach the country’s poorest regions. Indeed, before the Internet age, media and telecommunications development in the Global South was incipient, usually controlled by governments and local elites who owned a handful of biased private media outlets, operating under the disguise of “the free press.” Radio was the most accessible, but local populations lacked trust in media and public institutions. And yet, disinformation was pervasive.

The above poses a serious challenge to the mainstream framework that dominates disinformation research and deploys the concepts of disinformation, misinformation and malinformation as analysis drivers. For starters, disinformation research only took off in 2016, after the 45th U.S. President commenced to use “fake news” to shoot down mainstream media outlets (and all others) that disagreed with him. But indeed, disinformation has been consistently used for decades, if not centuries. More critical researchers will argue that colonialism is among the earliest forms of modern disinformation. Regardless, the core issue is that disinformation research in the Global South has yet to take off. Instead, we see that Global North disinformation agendas are being deployed everywhere, thereby disregarding history and local contexts.

Secondly, the dominant perspective implicitly suggests that disinformation, et al., is a tool mainly used by authoritarian regimes. Somehow, most democracies have been vaccinated against such a disease, thanks to the “free press.” However, historical evidence again shows otherwise. The many examples of global and imperial hegemons using disinformation to conquer or invade countries or topple governments they dislike—even if they are democratic regimes—should suffice. Nowadays, privately owned for-profit corporations are the top purveyors of disinformation and have attracted massive audiences, thus making substantial profits. Patriarchy, racism and communism, among others, have been consistent disinformation targets.

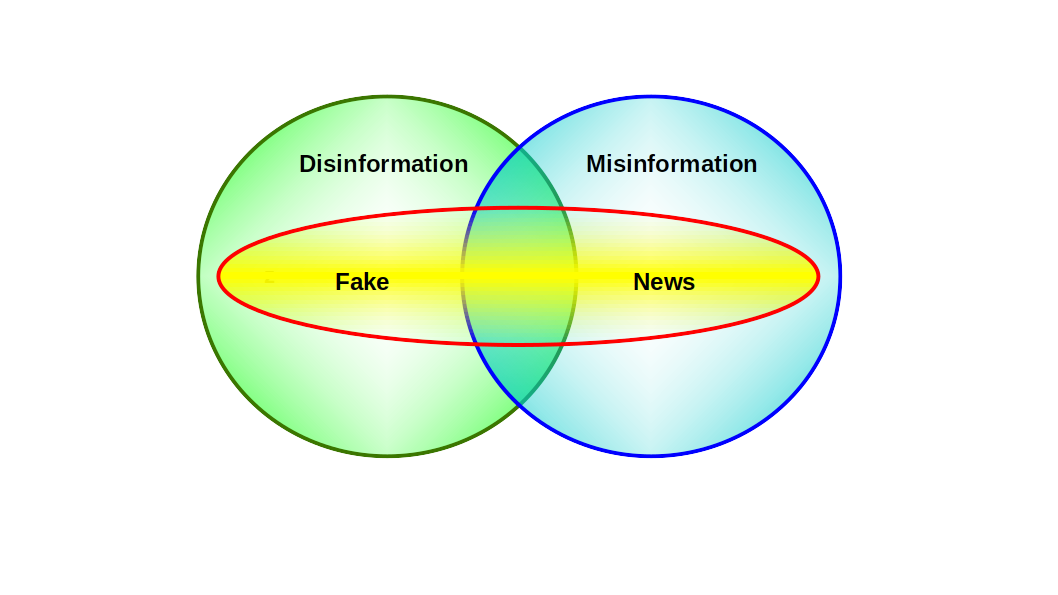

The notion that all disinformation is harmful or regressive is also pervasive. But in the case of In Evil Hour, we see that bottom-up disinformation poses a challenge to authoritarianism and its top-down disinformation platforms. Indeed, local communities know exactly who holds power and have experienced their nasty modus operandi firsthand. In fact, such a view directly stems from how the dominant disinformation framework defines its terms. It all boils down to individual intentionality. If the goal of the agent disseminating false information is to harm others, then the disinformation umbrella opens. If not, it is raining misinformation. Leaks, hate speech and harassment, though, get their own category (malformation) but are still harmful in all cases. Intentionality is, of course, very difficult to determine and measure in practice. Indeed, false information can have two or more hats, depending on the agent/user’s intentionality. The orthogonality among these categories is thus questionable and might lead to significant misinformation about disinformation. Moreover, translating the three terms into other languages can be very tricky, as many only have one word for describing the diffusion of false information.

Another way to look at the issue is by focusing more deeply on the impact of disinformation. In García Márquez’s little town, a false rumor led to the murder of an innocent man, which, in turn, challenged the political order. That is undoubtedly not only harmful but also lethal and politically destabilizing for those in power. On the other hand, the impact of the pasquinades on the whole town was notable. For villagers, it was a way to escape the otherwise dominant, boring narrative propelled by the godlike mayor, whom no one really loved or even liked. But for the mayor, it was a golden opportunity to impose his will by force and make a lot of money in the process.

In this realm, power and its distribution are critical, regardless of hidden intentionalities.

Raúl