Unexpectedly, the ongoing pandemic has enshrined national states as the indisputable leader in pushing back the deadly SARS-CoV-2 pathogen. It now seems evident that no other sector in society is better positioned to effectively confront the virus that needs no passport to freely travel around the globe. Indeed, state action has thus been swift most times. Yet, the pandemic has evidenced that state capacity across geographies varies substantially, many countries lacking the capabilities and resources to respond effectively.

Bringing the state back in yet one more time is a friendly reminder of its relevance in the overall process of public policy formulation. Indeed, public policy approval is solely under the purview of the Government and its three branches. While consultation with all other non-state sectors and stakeholders should also be part of the process, public policymaking is one of the core traits of national states. Consequently, it can have an indelible impact on local populations in the medium and long term.

In the digital arena, policymakers have at their disposal a wide range of tools to design and formulate public policies. Strategies, policies, regulations, road maps, standards, procedures and guidelines are part of officials’ policy arsenal to advance existing and emerging digital policy agendas. However, more often than not, the sharp conceptual line differentiating such policy tools becomes blurry. As a result, the much-needed sequencing among these tools is lost in the shuffle, diminishing the efficacy and impact of public policy nationally.

By all means, digital policymaking is not a purely technically complex exercise. While capacity, knowledge, and expertise are required, policymaking is also subject to national and international policy functuations and political changes that influence and shape the policy agenda. The emerging Digital Transformation global push and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are good examples.

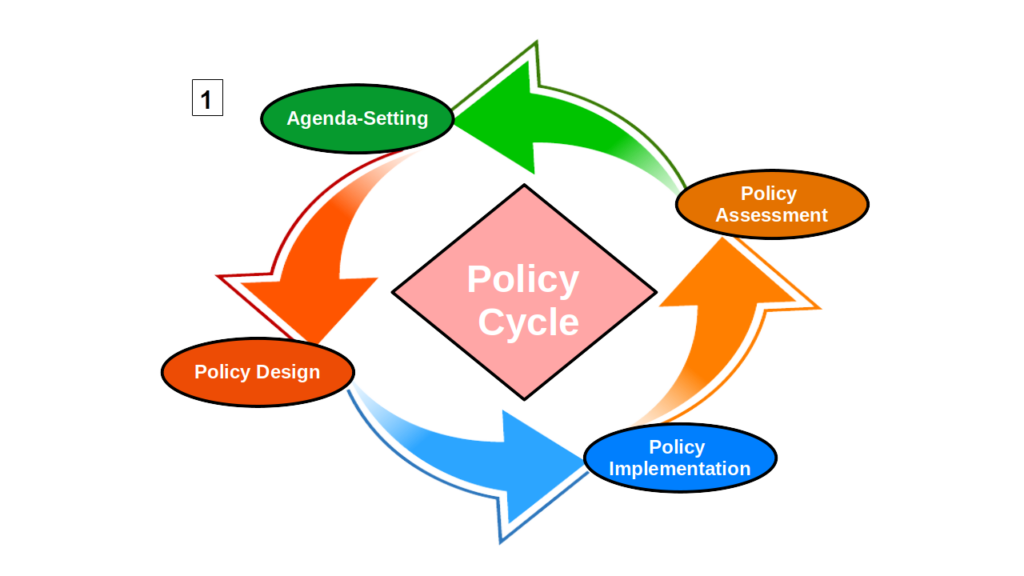

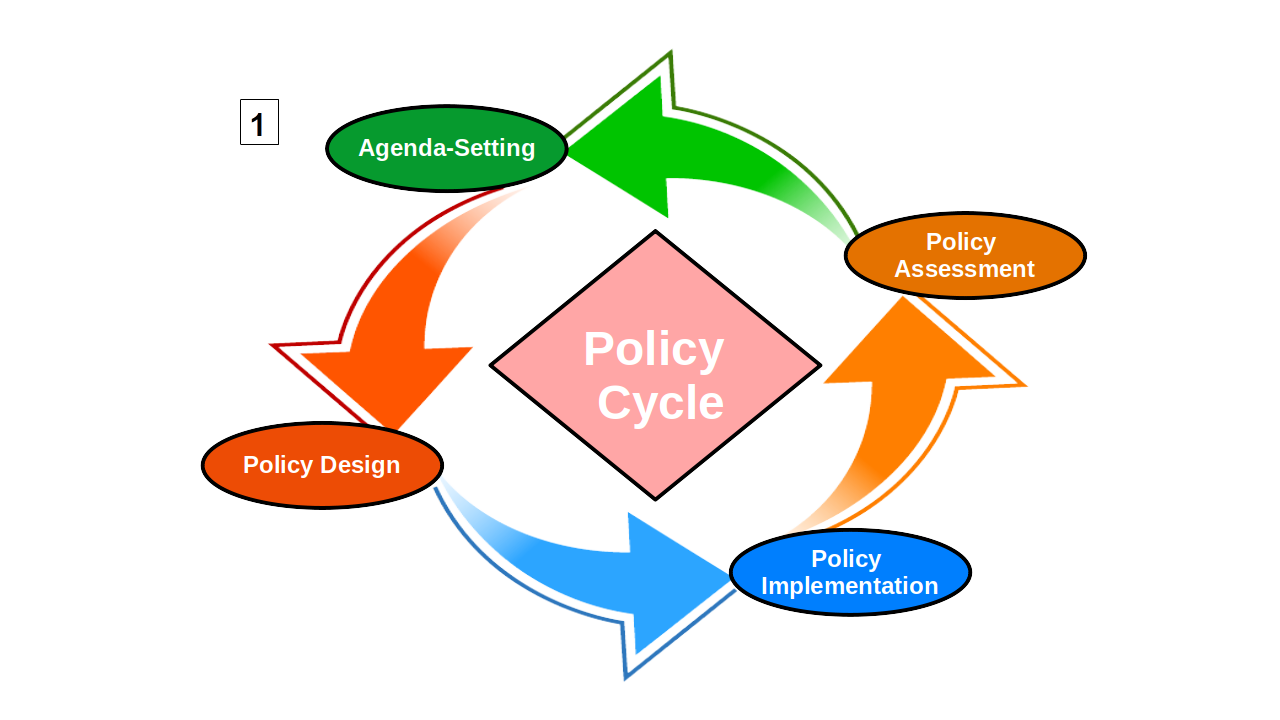

The Policy Cycle optimally captures the public policymaking process by depicting the steps required to develop any public policy dynamically. The policy cycle is the policymaker’s best friend. The same goes for stakeholders trying to influence policy agendas and add their voices to the final policy document. The policy cycle has been around for decades and has thus evolved throughout the years – critical perspectives included.

For our purpose here, I will be using its most straightforward model, depicted below.

The policy cycle comprises four tightly interrelated dimensions. First is the Agenda-setting process. Here, policymakers and stakeholders should agree on a set of themes, gaps and priorities that the policy should address. That is a critical step, as introducing missing target areas a posteriori might be cumbersome, impeding a cohesive policy design process. Note that this first step in public policymaking can be contentious as different parties and sectors might have diametrically opposed perspectives on specific digital topics. An open, inclusive and participatory governance structure is thus required to ensure policy agendas can be completed successfully. Unfortunately, more usually than not, many of the stakeholders that should be involved in the agenda-setting phase of the process have a hard time getting a seat on the table. Moreover, academics and researchers wishing to share inputs with policymakers and stakeholders should do so at this stage and not during the policy design phase – as it is usually done.

The policy cycle comprises four tightly interrelated dimensions. First is the Agenda-setting process. Here, policymakers and stakeholders should agree on a set of themes, gaps and priorities that the policy should address. That is a critical step, as introducing missing target areas a posteriori might be cumbersome, impeding a cohesive policy design process. Note that this first step in public policymaking can be contentious as different parties and sectors might have diametrically opposed perspectives on specific digital topics. An open, inclusive and participatory governance structure is thus required to ensure policy agendas can be completed successfully. Unfortunately, more usually than not, many of the stakeholders that should be involved in the agenda-setting phase of the process have a hard time getting a seat on the table. Moreover, academics and researchers wishing to share inputs with policymakers and stakeholders should do so at this stage and not during the policy design phase – as it is usually done.

Once the agenda has been set, policymakers can start the Policy Design process. Bear in mind that the central objective of any given policy is to set overall direction. For example, suppose the theme of the policy is Artificial Intelligence (AI). In that case, the policy should identify the direction the country wants to take and the possible paths to get there. In that context, the core pillars identified in the agenda-setting phase of policy development should be detailed and sync up dynamically, hopefully. In broad terms, this phase has two distinct components. First, policy formulation comprises the design of the policy itself and the actual writing of the various policy drafts that should be submitted for stakeholder feedback at multiple points. Second, once consultations are completed, the draft policy is shared with key government decision-makers who eventually approve the policy and publish it via official communication channels. Alternatively, policies can also be introduced as bills endorsed and approved by the national legislative assembly.

Policy Implementation follows. Here, the entire focus is on the rollout of the approved policy. Regulations, legislation, road maps, and standards, among others, are part of the process. Creating an overall policy governance instance in government and identifying the various actors involved in implementation is critical here. The set of capacities, skills and resources required to propel this phase of the policy cycle are utterly different from those of the previous two policy phases. In this light, an institutional firewall between policy and implementation is required and recognized as an international best practice. Identifying the institutional spaces and partners for policy implementation is also of fundamental importance.

Taking stock of the policy implementation is the core objective of the Policy Assessment dimension. Identifying gaps and challenges, capturing lessons learned and best practices is vital here. These can then become critical inputs for revisiting the policy agenda and restart the process with renewed impetus. But, again, timing is essential here as policy implementation usually requires a few years before popping up in indicators.

I will consider the relationship between the policy cycle and the digital policy tools mentioned above in the next post.

Cheers, Raúl

Comments

2 Responses to “Digital Public Policy Development – I”