Apps and data

Almost five years ago, while working together with former UN colleagues, we decided to create a mobile app that could show data on the progress towards the achievement of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The key purpose of the project was to raise awareness of people in general on how the MDG targets (almost 50 of them) were moving in time at the national level. The app also allowed to compare targets across countries as well as aggregate data by regions.

Developing the app, which we did initially for Android mobiles, was the easy part. Getting the actual data however proved to be an almost insurmountable challenge. While a few countries did have available data, getting official data for most of them was complicated as in some case the data did not exist in digital format for example. The source and quality of the data were also challenging. On the other hand, we knew that data produced by the private sector, including private non-profits) was handy for some countries but this posed a political challenge as such data had not been endorsed by national governments. Given our institutional framework, we could not make good use of these sources. We thus ended abandoning the project with a fully functional app but with more than half of the countries with almost no data. Oh yes, the app was called mMDGs (small m stands for mobile!), and the source code is still available.

Developing the app, which we did initially for Android mobiles, was the easy part. Getting the actual data however proved to be an almost insurmountable challenge. While a few countries did have available data, getting official data for most of them was complicated as in some case the data did not exist in digital format for example. The source and quality of the data were also challenging. On the other hand, we knew that data produced by the private sector, including private non-profits) was handy for some countries but this posed a political challenge as such data had not been endorsed by national governments. Given our institutional framework, we could not make good use of these sources. We thus ended abandoning the project with a fully functional app but with more than half of the countries with almost no data. Oh yes, the app was called mMDGs (small m stands for mobile!), and the source code is still available.

While we can certainly draw many lessons from this experience, one that is key from the open data perspective is the lack of public data in many developing countries. By public I mean data that is collected by national governments, financed by public resources and is, in principle, available at little to no cost) to people (more on this concept is in a previous blog here). In any event, this situation has not changed much since.

Data collection

The seemingly lack of public development data is perhaps puzzling if we consider that most if not all countries have National Statistical Offices (NSOs). That is, they have a unit (or units) somewhere in government, backed by public resources, whose exclusive mission is to collect, process, store and share public data. The UN Statistics Division maintains a list of all NSOs, including a brief profile and history of each. The UN has also published the 10 Fundamental Principles for NSOs (pdf), endorsed by all UN member states, which for example includes guidelines for the protection of personal data collected by governments.

Historically, NSOs have received support from both the UN and donor countries to develop national statistical capacities. The 1993 UN System of National Accounts (SNAs), completed with support from the IMF, OECD and EuroStat, laid a common framework for the collection of mostly macro-economic and financial data using common standards. And along with this came support to strengthen NSOs.

In 2004, at the Second International Roundtable for Managing for Development Results held in Morocco, over 100 countries endorsed the Marrakesh Action Plan for Statistics (MAPS) which aimed at improving the generation of development statistics. In 2011, at the Busan High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, a new action plan for statistics was endorsed. The emphasis of the latter was on data related to transparency, accountability and results thus going beyond traditional economic and financial data collection but at the same time adding more demands on NSOs for the production of data.

When it comes to ICTs, efforts have been made by the Partnership on Measuring ICT for Development to promote the inclusion on ICT indicators in the collection of data by NSOs. Their latest report was presented to the UN in 2014 and includes over 50 ICT-related indicators. The Partnership is also working on SGD-related indicators and has completed work on e-government indicators.

Altogether, it seems that support for NSOs has been in place for a few years now and significant progress has been made since (see an update by the World Bank here). Yet, we still do not have reliable national data on the now moribund MDGs for many countries.

One reason for this particular outcome can be seen from the above description. Historically, we can see that macro-economic and financial data were set as critical priorities for NSOs. It is only recently that other types of data are receiving well-deserved attention. In other words, the generation of non-economic development data is just starting to take off in developing countries. Another factor that might be impacting development data production is the increased national and international demand for new types of data that NSOs are supposed to generate. However, budgets and capacity of NSOs seem to be growing at a much slower pace thus creating both a gap and a lag in the process.

Being that as it may, additional research is required to come up with a definitive answer here. But the main point here is that non-economic development data is not being adequately produced in many developing countries, especially the poorer ones.

Political economy of (open) data

We thus need to take a quick step back and see what ingredients are necessary to make sure development data is widely available in all countries. And this is where a political economy approach can become handy. Here we can find two key layers. First, we need to carefully consider the production, distribution (exchange included), and consumption (PDC) of data. These three layers are tightly connected but start with production. If data is not being produced, then we will be in a void. The second inter-related layer is the socio-political context in which PDC takes places. This is closely related to institutional development, political regime and relative strength of civil society and non-state actors in general, among others. If say development data is not being adequately produced then we will need to consider the socio-political context to examine why this is the case and what can be done, if anything, to address this. This is indeed not just a technological issue.

We thus need to take a quick step back and see what ingredients are necessary to make sure development data is widely available in all countries. And this is where a political economy approach can become handy. Here we can find two key layers. First, we need to carefully consider the production, distribution (exchange included), and consumption (PDC) of data. These three layers are tightly connected but start with production. If data is not being produced, then we will be in a void. The second inter-related layer is the socio-political context in which PDC takes places. This is closely related to institutional development, political regime and relative strength of civil society and non-state actors in general, among others. If say development data is not being adequately produced then we will need to consider the socio-political context to examine why this is the case and what can be done, if anything, to address this. This is indeed not just a technological issue.

Great concepts such as open data and open government carry an important socio-political message demanding more openness, transparency and accountability of governments – and the private sector. Such demands, although welcome by most, will necessarily face institutional constraints of various types in many countries, and probably more so in developing countries. A change process thus needs to be started, process that might not complete its due course in the short term. Furthermore, many open data initiatives for example seem to assume that public data is readily available and thus focus on the distribution and consumption of data.

Data Production

Nowadays, data is being produced in quantities unheard before in human history thanks to the evolution of the Internet, mobile technologies and broadband, among others. However, as reported by The Economist last year, most of this data is being “produced” by private companies, not governments. Nowadays, data is quite an extensive business as companies will pay dearly to have it handy to foster marketing, improve product development, increase sales, etc. Let us call this business data for the moment.

The second big change here is the way data is being “produced”. Thanks to the new ICTs, data is actually furnished to private companies by end users who freely and willingly share data, including personal information, on digital platforms that are (almost) freely available to them. There is some sort of in-kind exchange which some observers have labeled as the “gift economy”. In any event , the cost of data collection has gone down substantially compared for example to the old way of getting data via surveys, interviews, etc. Here we have both a qualitative (“free” data collection) and quantitative (many more people furnishing much more data) change in the data production process.

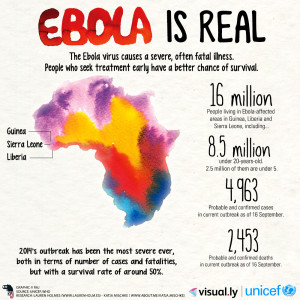

These changes also blur the distinction between business data and most other data, including personal data and development data. As end users furnish data of all sorts, then it is also feasible  to use it for addressing global public and development issues. This is particularly true for areas which are information-rich such as health and education for example. We all have heard about Google’s flu predictions (which in the end did not work that well) using big data and machine learning algorithms. On the other hand, we are also well aware of the Ebola crisis where data was not readily available, and it was almost impossible to predict from a data point of view. In the latter case, many donors and NGOs had to create new data to be able to track and manage the crisis accordingly.

to use it for addressing global public and development issues. This is particularly true for areas which are information-rich such as health and education for example. We all have heard about Google’s flu predictions (which in the end did not work that well) using big data and machine learning algorithms. On the other hand, we are also well aware of the Ebola crisis where data was not readily available, and it was almost impossible to predict from a data point of view. In the latter case, many donors and NGOs had to create new data to be able to track and manage the crisis accordingly.

We can thus detect a “data (production) divide” among countries – and even within countries. This divide seems to pretty much have similar characteristics as the now old “digital divide” -which in turn is mostly a reflection of existing socio-economic divides, particularly in less developed countries. Indeed, latest data by the ITU suggests that less than 40% of the world’s population is connected to the Internet, and most of the 4 billion plus lacking access are in developing countries. They are indeed missing the “data revolution” as they are not able to access data and neither they contribute their own data to the (almost) free digital platforms which are readily available today.

This, combined with the fact that NSOs are lagging in the production of relevant non-economic development data, suggests that efforts should be made to create relevant development data that is open and sustainable in the long run. Here, public-private and multi-stakeholder partnerships can be of critical importance to address the issue in the short run, while thinking of the institutional settings that will be required to ensure this happens on a recurrent basis from here on in.

A recent report by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network makes a case along the same lines, while asking donors to support NSOs in a selected group of poor countries.

But this is not the end of the issue. More to come soon!

Cheers, Raúl