Innovation has taken the world by storm. More than a pure storm, it is now looking more like a stationary looping hurricane. No escape. Embrace or die. Only a few have opted for the latter. In any event, this is, without doubt, a critical development. New technologies are creating wave after wave of innovation, perhaps on a scale not ever seen before. They are, in fact triggering significant changes at most levels of society, from personal relations and family to politics and conflict management.

It is usually assumed that the innovation brought forward by new technologies is almost always positive. However, when it comes to diffusion, we regularly hear about the rapid diffusion of new technologies on a global scale, mobile phones being the most frequently quoted example. Some even speak about the “democratization” of access to new technologies, which in theory creates a global level playing field where people from all walks of life can be part and parcel of economic, political and governance processes.

It is usually assumed that the innovation brought forward by new technologies is almost always positive. However, when it comes to diffusion, we regularly hear about the rapid diffusion of new technologies on a global scale, mobile phones being the most frequently quoted example. Some even speak about the “democratization” of access to new technologies, which in theory creates a global level playing field where people from all walks of life can be part and parcel of economic, political and governance processes.

This view is complemented by the notion that innovation will positively impact regardless of the level of development of a given country. In other words, countries are assumed to be standing on the same pedestal and thus should be capable of innovating similarly.

But can we safely make such assumptions? Probably not.

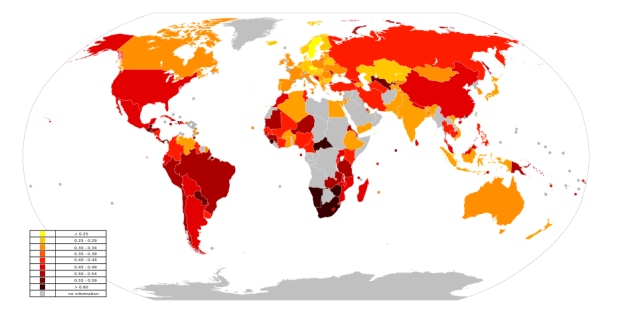

One way to revisit these assumptions is by thinking a bit more on the link between new technologies, innovation, and inequality. Does innovation foster greater inequality or, on the contrary, does it tends to create a flatter world? Yes, the “democratization” argument seems to support the latter. But, on the other hand, soaring socioeconomic inequality on a global scale in the last 15 years seems to help the former.

The book, edited by Susan Cozzens & Dhanaraj Thakur (complete reference at the end of this blog), addresses some of these questions from the perspective of Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI), and Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICTD). Focusing on five new technologies and their spread and diffusion in eight countries, including both developed and developing, the authors shed light on some issues. Note that biotechnology and nanotechnology are part of the analysis, thus not limited to ICTs only.

The book has four main parts. The first one presents an analytical framework that can provide the tools to respond to the main questions. The second part introduces the five technologies under study: recombinant insulin, GM corn, mobile phones, open source software, and open source biotechnology. The third part dedicates a chapter to each of the 8 countries under consideration (Argentina, Canada, Costa Rica, Jamaica, Germany, Malta, Mozambique, and the US). And the final section of the book presents the lessons learned as well as some overall recommendations.

Without a doubt, emerging technologies are, for the most part, “disruptive.” While they can provide new solutions to long-standing problems, they can at the same time propel “creative destruction” (a la Schumpeter) by eliminating jobs, sectors, and industries in some countries. However, since they are new, they are also “malleable: the appropriation process of new technologies can be accomplished in many different ways, including promoting greater equality. Secondly, most recent innovations seem to have relatively high prices. They also demand top skills for their production and, in some cases, acceptable use. This in itself can actually promote inequality from the onset.

Finally, most new technologies and innovations are usually first developed in the Global North and then diffused globally. However, the costs and benefits for their creation, production and consumption vary substantially across countries. To address these issues, developing countries, in particular, need to invest in improving absorptive and adaptive capacities to harness the new technologies and address local needs and have national policies and regulations for STI and ICTs. There are many options here, but the point remains that countries are not on the same playing field.

The analytical framework used for the analysis is based on three streams of knowledge: Science and Technology Studies (STS); Science and Innovation Policy Studies, and the Economics of Innovation.

STS are usually focused on how “social actors understand and use technologies” (pg. 6) but not on how it impacts people’s lives. And when they do, they are usually focused on middle-class technology consumption in rich countries with almost no reference to developing countries. Some STS studies focus on so-called horizontal inequalities (gender, race, etc.), usually culturally defined. Our editors pick the STI concept of “technological project,” which envisages the existence of local champions who promote some specific technology and interact with the local environment at various levels. The assumption here is that technology, society, and inequality evolve together; that technology projects are inherently distributional; and that the distributional aspects of technology projects are open to choice and not cast in stone.

Inequality is not part of mainstream research on Science and Innovation Policy Studies. It is usually assumed that by default, innovation propels economic growth. Thus, inequality issues are dealt with by separate and specific redistribution policies that can help spread the wealth it creates. However, new approaches to the problem suggest that innovation policies tend to increase inequality unless they are purposely designed to do otherwise. The empirical evidence on this is weak at best. And one of the objectives of the book is to furnish some new evidence on this. In any event, it seems clear that we need to start looking beyond innovation alone and bring into the picture other regulatory areas.

Inequality is not part of mainstream research on Science and Innovation Policy Studies. It is usually assumed that by default, innovation propels economic growth. Thus, inequality issues are dealt with by separate and specific redistribution policies that can help spread the wealth it creates. However, new approaches to the problem suggest that innovation policies tend to increase inequality unless they are purposely designed to do otherwise. The empirical evidence on this is weak at best. And one of the objectives of the book is to furnish some new evidence on this. In any event, it seems clear that we need to start looking beyond innovation alone and bring into the picture other regulatory areas.

Economics of innovation studies are usually focused on vertical inequalities (rich vs. poor). While economics tends to see technology as a black box, the economics of innovation is based on evolutionary economics, which deals with technical change in firms and overall governance conditions. For the purposes of the book, it is assumed that not all technical changes are limited to firms alone which in turn opens the door for broader governance considerations in the analysis. Furthermore, using the concept of technological project, the distinction between innovation and diffusion becomes blurred. Instead, a “co-evolutionary” approach is taken where these two categories take place at the same time. No S innovation curves are needed here. Instead, we need to look at technology ownership, the business models used to deploy and diffuse it, the technology’s direct beneficiaries, and the losers in their production and use.

In the end, the book editors conclude that technology projects led by local champions can go in many different directions depending on the local environment. Involving stakeholders and other partners in the process can lead to better distributional effects if socioeconomic gaps are factored in from the very beginning. The same goes for the private sector who should promote technologies that can be used by those sitting at the bottom of the pyramid.

As for governments, the usual suspects are mentioned here: education, regulation, STI policies, etc. But the editors also see public procurement processes as critical for technology adoption, adaptation, and consumption. Finally, investments on state-of-the-art technologies in developing countries should be seen as strategic and not as a luxury, as long as such investment addresses specific local demands and priorities.

In sum, STI policies alone will not do the trick. It is also essential to consider non-STI policies related to specific social sectors such as health, education, etc. This, in turn, can lead to broader use of technologies that must also address local development issues and priorities. This is particularly the case for many developing countries which can be torn between being innovators and addressing pressing human development gaps. These are indeed not mutually exclusive. More often than not, the issue is that they are not strategically linked at the policy and implementation levels.

Cozzens, Susan & Dhanaraj Thakur (eds.). 2014. Innovation and Inequality: Emerging Technologies in an Unequal World. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.