After remittances and land titles, refugees are perhaps one of the primary targets of blockchain technology (BCT) initiatives promoting development or social impact. Bitnation, Aid:Tech and the UN World Food Programme, among many others, are good examples. Last month, at a BCT meeting in New York, UN Women shared its plans to launch a blockchain lab in early 2017. And women refugees are a top priority in the lab’s agenda.

No doubt refugees have become a critical issue of global scope, especially after the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Syrians in the last few years. Syrians escaping civil war had no choice but to leave their homes, belongings, and country seeking more peaceful and secure lands. What is different today is the scale of this forced migration which seems unprecedented in historical terms. The fact that most were heading to Western Europe has exacerbated the magnitude of the crisis. Unfortunately, the issue has now been politicized, and somehow refugees became first blood cousins with undocumented migrants – and terrorism.

In ant event, tackling the issue using new technologies should then not surprise anyone.

What the data says

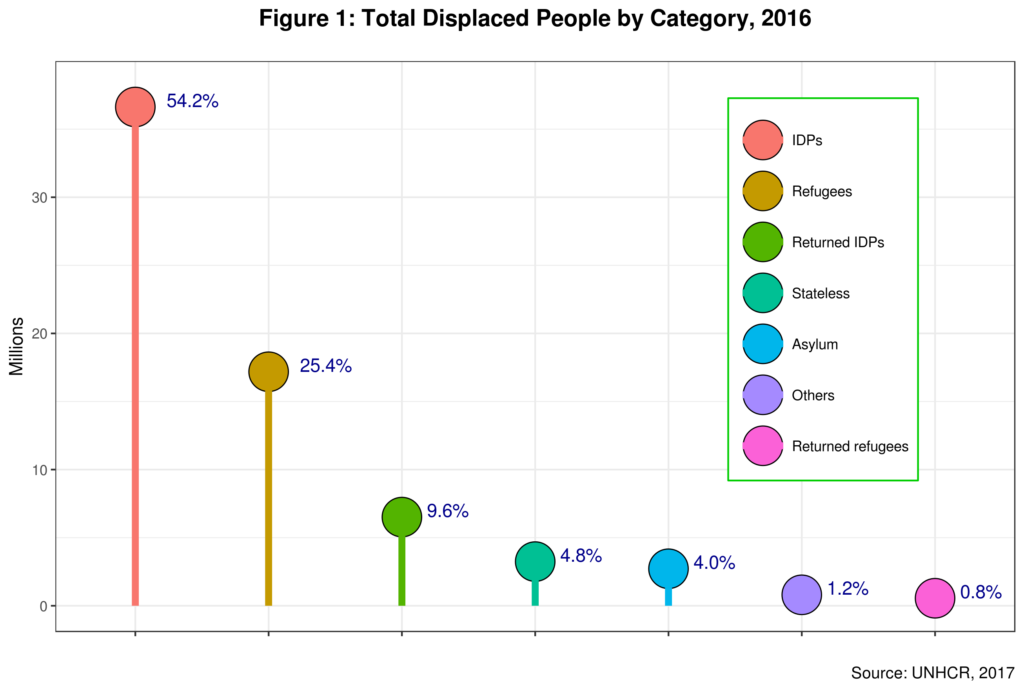

UNHCR reports that by the end of 2016, 67.7 million people were considered “persons of interest” under their mandate. This number includes not only refugees but also people that have been forcibly displaced in some fashion. Figure 1 presents the distributions of the various categories defined by the organization.1 IDPs stands for Internally Displaced Persons or “internal” refugees, so to speak.

The most salient feature shown by the graph is perhaps the fact that for every five refugees in the world there are eleven IDPs.2 This excludes the 5 million plus refugees not under UNHCR’s mandate. Note also the total number of forcibly displaced people includes refugees and IDPs that have been able to return back home, sometimes under very precarious conditions. Returnees amount to just over seven million people. The total number of actually displaced people is thus 60 million people, 60 percent of them being IDPs. I am however not aware of a BCT initiative targeting IDPs.

The most salient feature shown by the graph is perhaps the fact that for every five refugees in the world there are eleven IDPs.2 This excludes the 5 million plus refugees not under UNHCR’s mandate. Note also the total number of forcibly displaced people includes refugees and IDPs that have been able to return back home, sometimes under very precarious conditions. Returnees amount to just over seven million people. The total number of actually displaced people is thus 60 million people, 60 percent of them being IDPs. I am however not aware of a BCT initiative targeting IDPs.

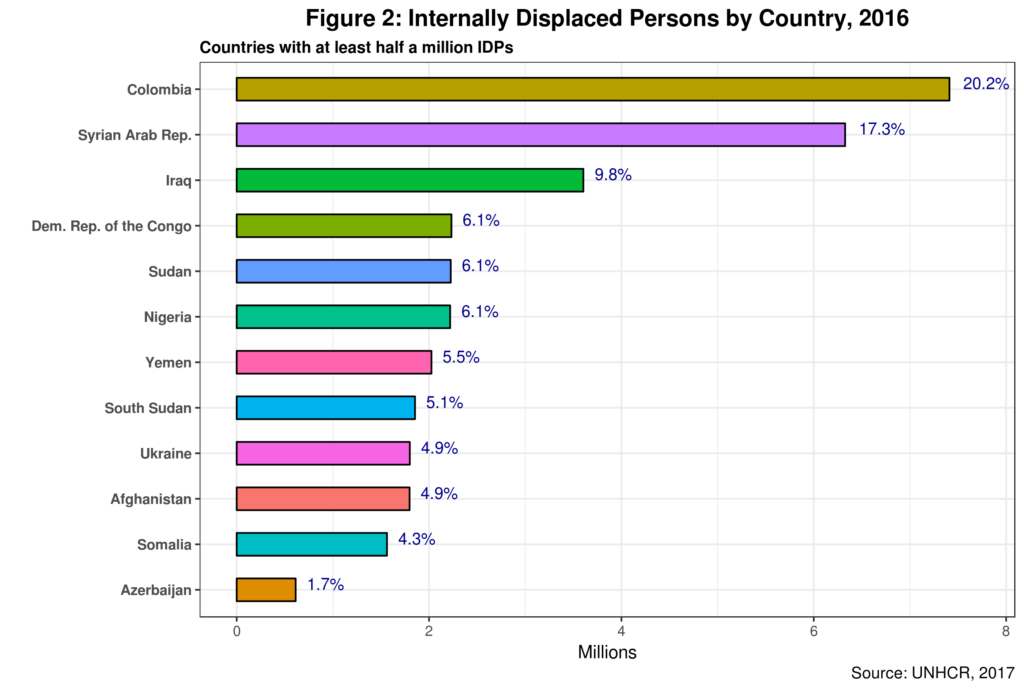

Figure 2 shows the distribution of IDPs for countries with more than one million people displaced.

Colombia, not Syria, takes the top spot, with 7.4 million IDPs, or 15% of its total population. Moreover, the number of Colombia’s IDPs has been consistently increasing for the last few years. It rose around 6% in 2016, in spite of the peace agreement and comprehensive policies and programmes put in place by the government to stop the process. Interestingly, IDPs are not a top priority in the political agenda as the country prepares for presidential elections next year.

Note also that the top five countries account for over 60 percent of all IDPs thus following the now well-known power distribution that characterizes the Internet economy. But in this case, we could perhaps speak of the distribution of the powerless. Finally, there is a high positive correlation between internally displaced people and social conflict and violence.

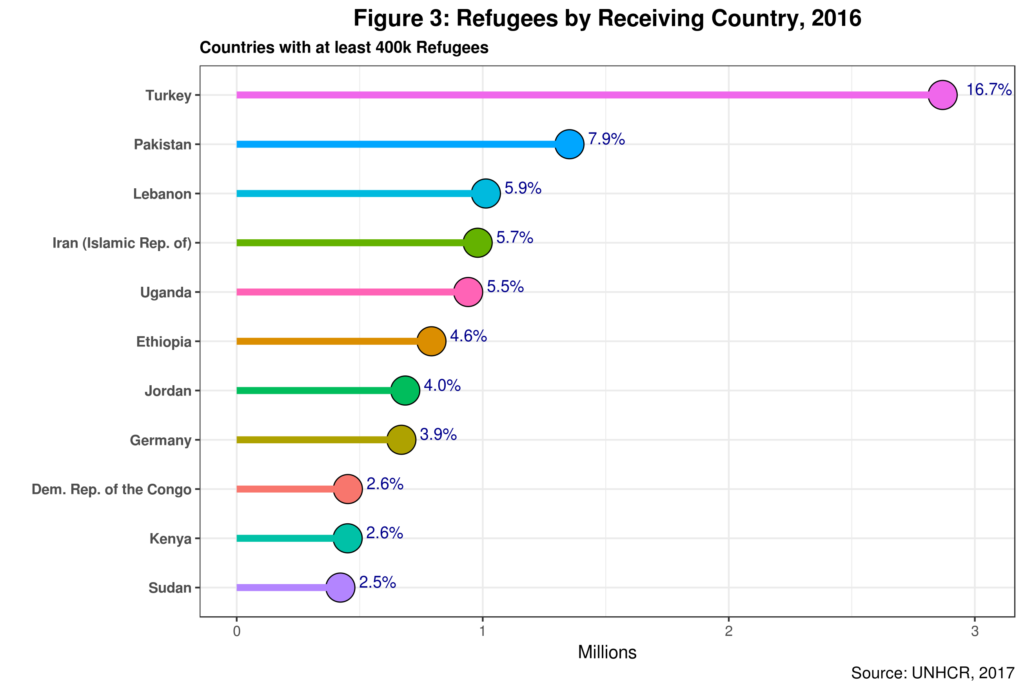

So where are the refugees? Figure 3 shows the top countries hosting refugees. And Turkey is the champion here hosting with a total of 2.8 million refugees, almost all of them coming from Syria. Moreover, over 50 percent of all refugees are in the top seven nations shown in the graph, all being developing countries. Germany is the only industrialized nation that has recently taken in a significant number of people escaping conflict and violence.3 Sweden, Austria, and Denmark follow but with a relatively smaller number of refugees.

a total of 2.8 million refugees, almost all of them coming from Syria. Moreover, over 50 percent of all refugees are in the top seven nations shown in the graph, all being developing countries. Germany is the only industrialized nation that has recently taken in a significant number of people escaping conflict and violence.3 Sweden, Austria, and Denmark follow but with a relatively smaller number of refugees.

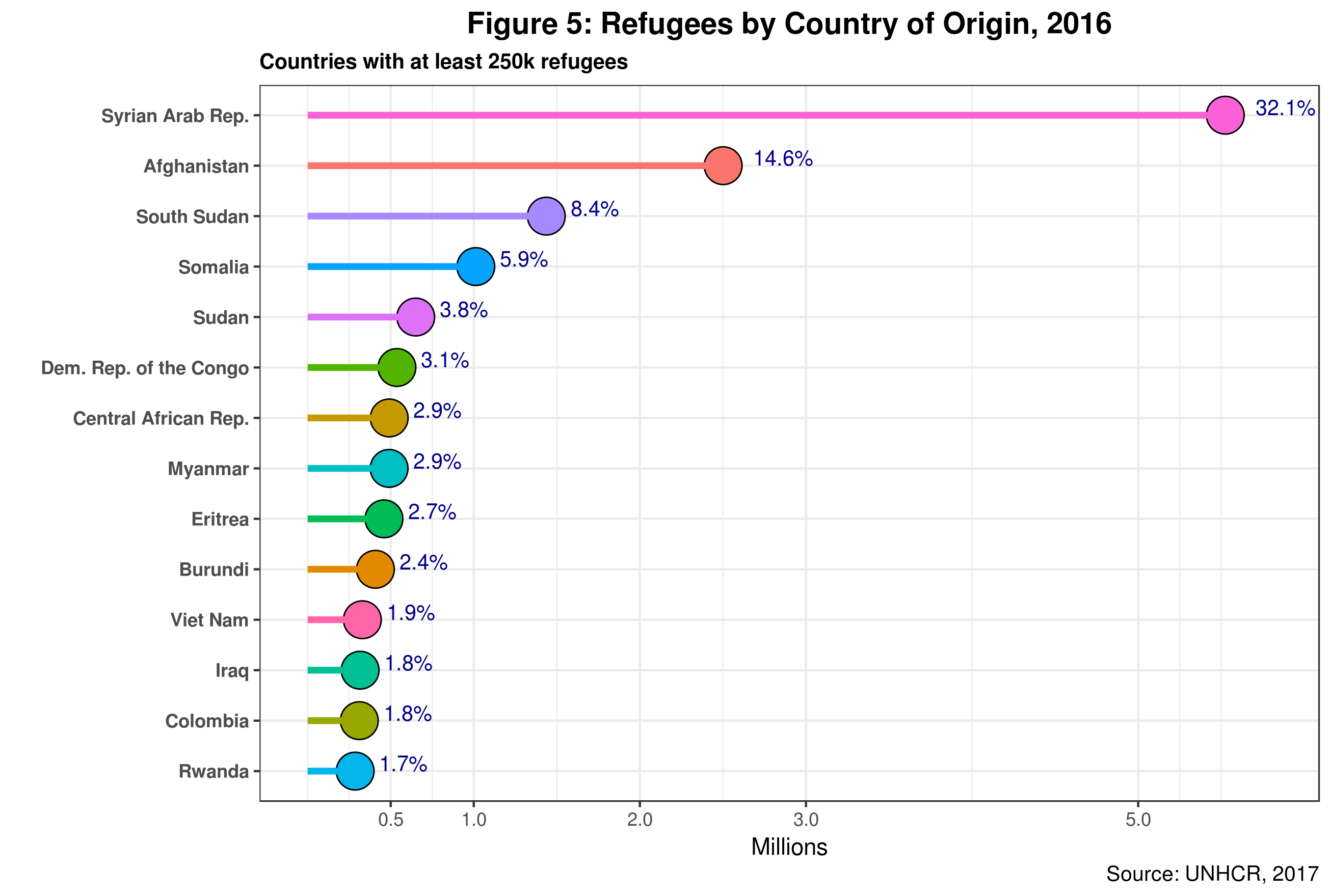

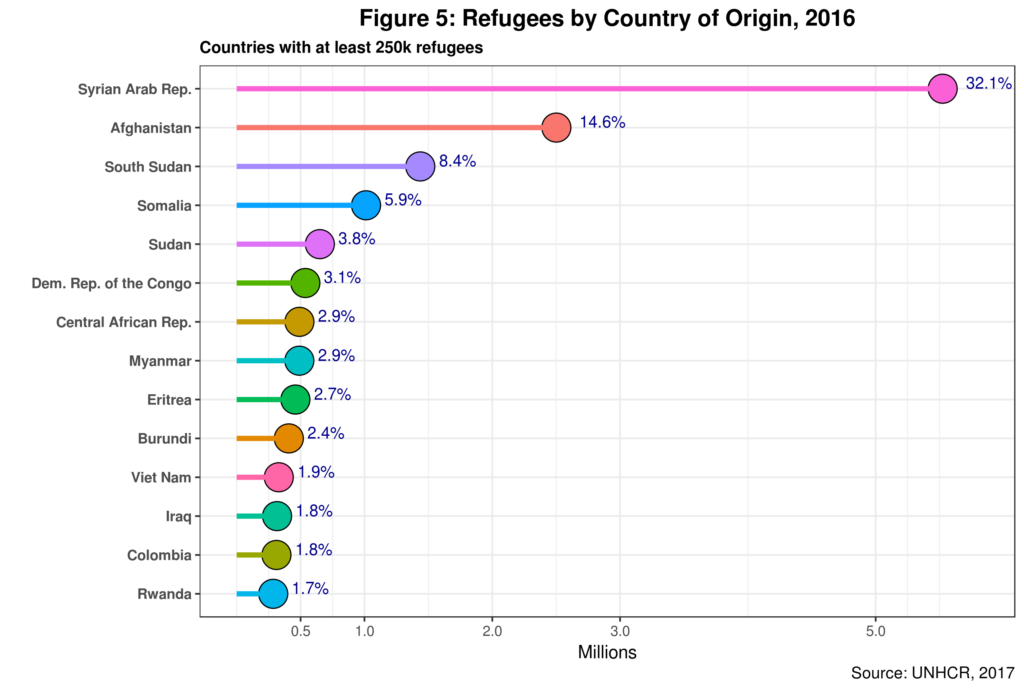

Finally, figure 4 shows the distribution of refugees by country of origin. Not surprisingly, Syria is at the top representing almost one-third of all refugees. And the top three countries account for nearly 55 percent of all the displaced migrating to foreign countries. Note that Colombia also makes an appearance here.

And the top three countries account for nearly 55 percent of all the displaced migrating to foreign countries. Note that Colombia also makes an appearance here.

Way forward

Primary data such as the above can provide initial guidance to tech innovators and entrepreneurs focusing on social impact on both the core issues a specific social area is facing, as well as about is current geography. More often than not, disruption is seen as a way to erase or replace what is currently on the ground. While this might be needed in some cases, in most others a better strategy is to carefully explore ways in which new technologies can address current gaps and bottlenecks by furnishing innovative solutions not previously available.

This requires practitioners acquire the necessary knowledge about the social area they want to tackle to then find ways to enhance delivery on the ground. Such delivery, in the end, must have a direct impact not on the technology per se but on the people who are supposed to be the beneficiaries of the intervention. Disruption could this be much more effective if it can amplify ongoing efforts to address social gaps and issues.

In the case of people forcibly displaced, we now know who are the most affected (IDPs) and where are most of them located. Technology-driven initiatives should thus explore this territory first and foremost, including BCT startups.

Land restitution is one of the critical challenges for IDPs wanting to return home. In many cases, land has been appropriated by third parties not related to the actual owners. In these instances, IDPs must somehow demonstrate land ownership which could be an incredibly complex process. On the other hand, land titles are one of the leading areas of BCT activity. It seems to me that supporting land restitution processes could offer a golden opportunity for BCT practitioners promoting social impact around the globe.

Identity access and management of the displaced is also another area where BCT could have considerable impact. While some refugees are already benefiting from the technology, the same cannot be said about IDPs.

Cheers, Raúl